This sixth video in a series celebrating Hubble’s 25th anniversary explains how Hubble has helped scientists study exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system, as never before.

“Oh Planet, What Art Thou?” This episode of “Hubble at 25” uncovers Hubble’s key role in the study of planets beyond our own solar system. Thousands of “exoplanet” candidates have been discovered. While Hubble is not responsible for most exoplanet detections, it is able to examine the chemical compositions of their atmospheres. Since these planets are too far away to ever visit in the foreseeable future, analyzing their atmospheres provides critical clues about the existence of life elsewhere in the universe. Credit: STScI

When Hubble was launched in 1990, the only planets we knew about were those orbiting our own sun. Since then, astronomers using both space-based telescopes such as NASA’s Kepler observatory and ground-based telescopes, have discovered a rapidly-growing number of so-called exoplanets around other stars.

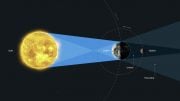

“One main way we have found planets is by the transit technique,” said Sara Seager, Professor of Planetary Science and Professor of Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, Massachusetts. “That is when a planet goes in front of its parent star as seen from the telescope. The observed starlight drops by a tiny amount, by 1 percent or even less. And by measuring a star’s brightness. Minute-by-minute or hour–by-hour or day-by-day, we are able to spot a planet transit.”

With Hubble, scientists can go beyond measuring basic properties of transiting planets, like their mass and their size, to actually studying their atmospheric composition. They do that using spectroscopy. The light from a star with a transiting planet is spread out by Hubble’s spectrographs into its constituent colors, or wavelengths. Some of this starlight will have passed through the outer atmosphere of the exoplanet. Scientists look for places in the color spectrum where light is missing, absorbed by gases in the atmosphere. Each gas has its own distinct set of lines it removes from the starlight spectrum, so particular gases in the planet’s atmosphere can be identified. With this technique, astronomers have identified sodium, nitrogen, hydrogen, and even water vapor in various exoplanetary systems.

The Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) is being used to study the abundance of water vapor in the atmosphere of exoplanets. WFC3 is also used to study how temperatures change in the profile (different heights) of an exoplanet’s atmosphere.

Studying the chemical makeup of an exoplanet may help find answers to the question of where life could exist elsewhere in the cosmos.

“I’d say my dream is to start my career as an astronomer and end it as a biologist,” said Dave Charbonneau, Professor of Astronomy at Harvard University. “So what I would really like to do is get at the question of life in the universe.”

The “Hubble 25th Anniversary” video series is produced by the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), Baltimore, which manages Hubble on behalf of NASA.

Be the first to comment on "How Hubble Has Helped Scientists Study Exoplanets"