A new and more precise recalculation of the normal background extinction rate — what it would be without the human presence — shows the rate to be lower, meaning that the rate of extinction in the human era is as much as 10 times worse than had been thought.

A new and more precise recalculation of the normal background extinction rate reveals that the rate of extinction in the human era is as much as 10 times worse than had been thought, finding that species die off as much as 1,000 times more frequently nowadays than they used to.

The gravity of the world’s current extinction rate becomes clearer upon knowing what it was before people came along. A new estimate finds that species die off as much as 1,000 times more frequently nowadays than they used to. That’s 10 times worse than the old estimate of 100 times.

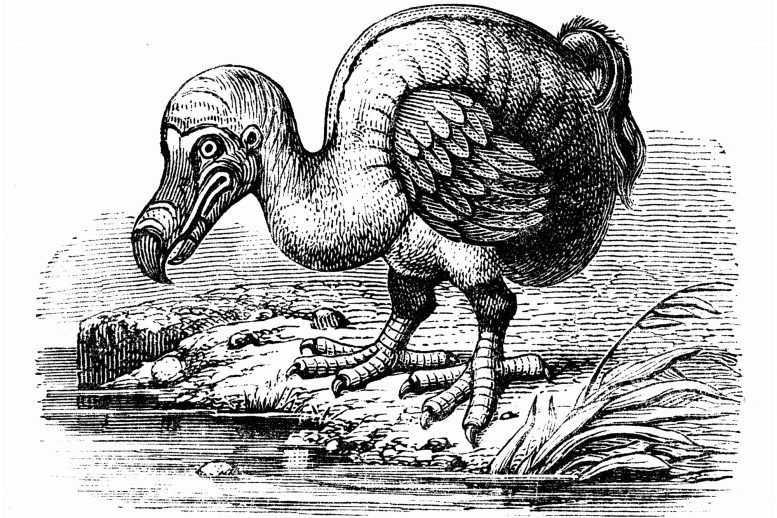

It’s hard to comprehend how bad the current rate of species extinction around the world has become without knowing what it was before people came along. The newest estimate is that the pre-human rate was 10 times lower than scientists had thought, which means that the current level is 10 times worse.

Extinctions are about 1,000 times more frequent now than in the 60 million years before people came along. The explanation from lead author Jurriaan de Vos, a Brown University postdoctoral researcher, senior author Stuart Pimm, a Duke University professor, and their team appears online in the journal Conservation Biology.

“This reinforces the urgency to conserve what is left and to try to reduce our impacts,” said de Vos, who began the work while at the University of Zurich. “It was very, very different before humans entered the scene.”

In absolute, albeit rough, terms the paper calculates a “normal background rate” of extinction of 0.1 extinctions per million species per year. That revises the figure of 1 extinction per million species per year that Pimm estimated in prior work in the 1990s. By contrast, the current extinction rate is more on the order of 100 extinctions per million species per year.

Orders of magnitude, rather than precise numbers are about the best any method can do for a global extinction rate, de Vos said. “That’s just being honest about the uncertainty there is in these type of analyses.”

From fossils to genetics

The new estimate improves markedly on prior ones mostly because it goes beyond the fossil record. Fossils are helpful sources of information, but their shortcomings include disproportionate representation of hard-bodied sea animals and the problem that they often only allow identification of the animal or plant’s genus, but not its exact species.

What the fossils do show clearly is that apart from a few cataclysms over geological periods — such as the one that eliminated the dinosaurs — biodiversity has slowly increased.

The new study next examined evidence from the evolutionary family trees — phylogenies — of numerous plant and animal species. Phylogenies, constructed by studying DNA, trace how groups of species have changed over time, adding new genetic lineages and losing unsuccessful ones. They provide rich details of how species have diversified over time.

“The diversification rate is the speciation rate minus the extinction rate,” said co-author Lucas Joppa, a scientist at Microsoft Research in Redmond, Washington. “The total number of species on earth has not been declining in recent geological history. It is either constant or increasing. Therefore, the average rate at which groups grew in their numbers of species must have been similar to or higher than the rate at which other groups lost species through extinction.”

The work compiled scores of studies of molecular phylogenies on how fast species diversified.

For a third approach, de Vos noted that the exponential climb of species diversity should take a steeper upward turn in the current era because the newest species haven’t gone extinct yet.

“It’s rather like your bank account on the day you get paid,” he said. “It gets a burst of funds — akin to new species — that will quickly become extinct as you pay your bills.”

By comparing that rise of the number of species from the as-yet unchecked speciation rate with the historical trend (it was “log-linear”) evident in the phylogenies, he could therefore create a predictive model of what the counteracting historical extinction rate must have been.

The researchers honed their models by testing them with simulated data for which they knew an actual extinction rate. The final models yielded accurate results. They tested the models to see how they performed when certain key assumptions were wrong and on average the models remained correct (in the aggregate, if not always for every species group).

All three data approaches together yielded a normal background extinction rate squarely in the order of 0.1 extinctions per million species per year.

A human role

There is little doubt among the scientists that humans are not merely witnesses to the current elevated extinction rate. This paper follows a recent one in Science, authored by Pimm, Joppa, and other colleagues, that tracks where species are threatened or confined to small ranges around the globe. In most cases, the main cause of extinctions is human population growth and per capita consumption, although the paper also notes how humans have been able to promote conservation.

The new study, Pimm said, emphasizes that the current extinction rate is a more severe crisis than previously understood.

“We’ve known for 20 years that current rates of species extinctions are exceptionally high,” said Pimm, president of the conservation nonprofit organization SavingSpecies. “This new study comes up with a better estimate of the normal background rate — how fast species would go extinct were it not for human actions. It’s lower than we thought, meaning that the current extinction crisis is much worse by comparison.”

Reference: “Estimating the normal background rate of species extinction” by Jurriaan M. De Vos, Lucas N. Joppa, John L. Gittleman, Patrick R. Stephens and Stuart L. Pimm, 26 August 2014, Conservation Biology.

DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12380

Other authors on the paper are John Gittleman and Patrick Stephens of the University of Georgia.

We need to start having bird safe glass used for windows and have the lights on water towers flash or blink rather than be constantly shining at night (to slow the rate of loss of dwindling bird populations)….making buildings and the environment safer for animals as much as possible by enforcing strict penalties for animal cruelty laws and larger fines for littering as well… and we can sacrifice things that we don’t really NEED to survive in order to help animals survive more easily such as not having fireworks on the 4th of July or cutting down Christmas tress that we throw out a month later that could’ve been used by the animals as much needed shelter which is already in short supply for animals to have space to even be able to survive…urban cities could stand to have more trees in their yards to give a place for animals to survive in urban settings rather than be a schmuck who buys animal traps or animal repel products such as spikes to prevent birds from using trees in your yard in order to prevent your precious stupid car from getting bird poop on it …since material things are way more valuable than the lives of potentially endangered species, right? :S If you agree, do the world a favor and go castrate yourself please. Bird poop actually slows the rate of global warming…https://www.audubon.org/news/how-bird-poop-helps-fight-climate-change That to me is more important to think about for human survival rather than some stupid paint job for your car if I had to choose between one or the other…

Idiot.

Humans are too busy making money and land grabbing to care about anything else.