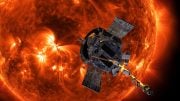

Watch the evolution of a stealth coronal mass ejection in this simulation. Differential rotation creates a twisted mass of magnetic fields on the sun, which then pinches off and speeds out into space. The image of the sun is from NASA’s STEREO. Colored lines depict magnetic field lines, and the different colors indicate in which layers of the sun’s atmosphere they originate. The white lines become stressed and form a coil, eventually erupting from the sun.

A newly published study details how astronomers developed a model that simulates the evolution of coronal mass ejections.

Our ever-changing sun continuously shoots solar material into space. The grandest such events are massive clouds that erupt from the sun, called coronal mass ejections, or CMEs. These solar storms often come first with some kind of warning — the bright flash of a flare, a burst of heat, or a flurry of solar energetic particles. But another kind of storm has puzzled researchers for its lack of typical warning signs: They seem to come from nowhere, and scientists call them stealth coronal mass ejections.

Now, an international team of researchers, led by the Space Sciences Laboratory at University of California, Berkeley, and funded in part by NASA, has developed a model that simulates the evolution of these stealthy solar storms. The researchers relied upon NASA missions STEREO and SOHO for this work, fine-tuning their model until the simulations matched the space-based observations. Their work shows how a slow, quiet process can unexpectedly create a twisted mass of magnetic fields on the sun, which then pinches off and speeds out into space — all without any advance warning.

Compared to typical coronal mass ejections, which erupt from the sun as fast as 1800 miles per second, stealth coronal mass ejections move at a rambling gait — between 250 to 435 miles (400 to 700 kilometers) per second. That’s roughly the speed of the more common solar wind, the constant stream of charged particles that flows from the sun. At that speed, stealth coronal mass ejections aren’t typically powerful enough to drive major space weather events, but because of their internal magnetic structure they can still cause minor to moderate disturbances to Earth’s magnetic field.

To uncover the origins of stealth coronal mass ejections, the researchers developed a model of the sun’s magnetic fields, simulating their strength and movement in the sun’s atmosphere. Central to the model was the sun’s differential rotation, meaning different points on the sun rotate at different speeds. Unlike Earth, which rotates as a solid body, the sun rotates faster at the equator than it does at its poles.

The model showed differential rotation causes the sun’s magnetic fields to stretch and spread at different rates. The researchers demonstrated this constant process generates enough energy to form stealth coronal mass ejections over the course of roughly two weeks. The sun’s rotation increasingly stresses magnetic field lines over time, eventually warping them into a strained coil of energy. When enough tension builds, the coil expands and pinches off into a massive bubble of twisted magnetic fields — and without warning — the stealth coronal mass ejection quietly leaves the sun.

Such computer models can help researchers better understand how the sun affects near-Earth space, and potentially improve our ability to predict space weather, as is done for the nation by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Reference: “A model for stealth coronal mass ejections” by B. J. Lynch, S. Masson, Y. Li, C. R. DeVore, J. G. Luhmann, S. K. Antiochos and G. H. Fisher, 18 October 2016, JGR Space Physics.

DOI: 10.1002/2016JA023432

arXiv

Be the first to comment on "Astronomers Create a Model for Stealth Coronal Mass Ejections"