New research reveals the physical basis for why approved antibody therapeutics are not working in neutralizing the recent COVID-19 variants of concern, such as Omicron and its subvariants.

The new peer-reviewed paper can help inform the development of new vaccines and therapeutics.

When SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 disease, first appeared, it was a single variant. Over time, the coronavirus evolved and new variants emerged including Alpha, Beta, Delta, Gamma, and Omicron. Unfortunately, researchers found that vaccines and therapeutics were sometimes far less effective against some of these variants.

But why? In a new study, scientists investigated the physical basis for why approved antibody therapeutics are not working in neutralizing the recent COVID-19 variants of concern, such as Omicron and its subvariants.

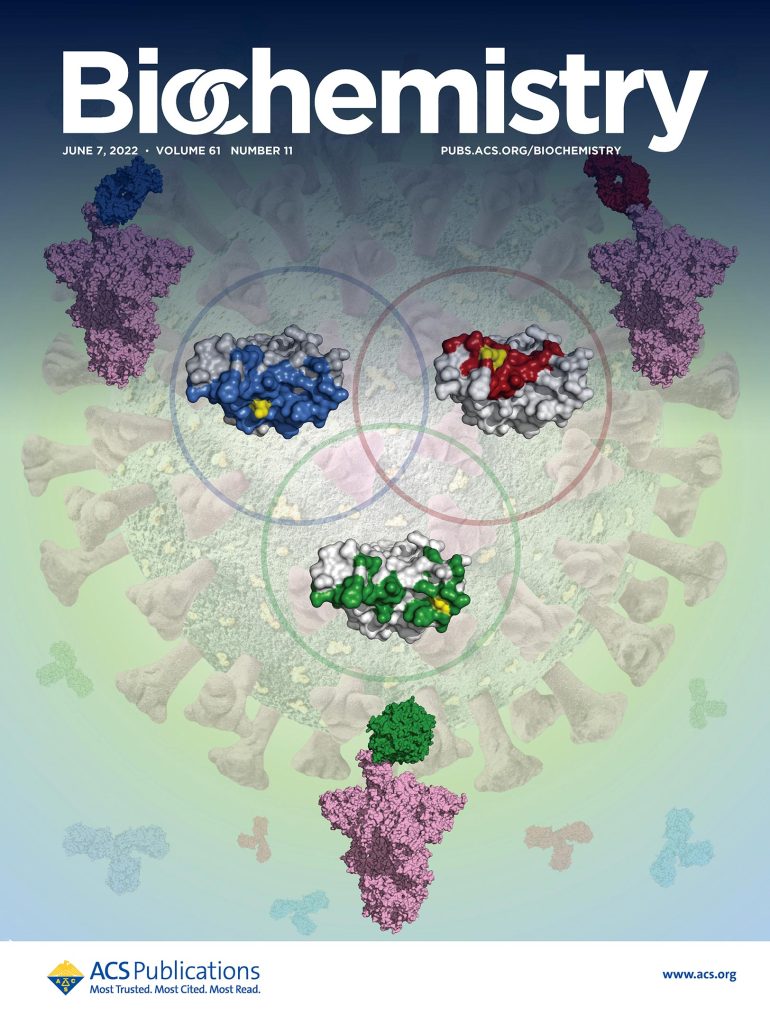

New research published in the June 7, 2022, issue of the journal Biochemistry is the first to explore the effects of multiple mutations in the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants. The findings can help scientists better understand the properties of current and new variants.

The results can also be used to better inform the development of vaccines and therapeutics to counter the threats posed by variants.

“Earlier studies, including ours, have focused on explaining the effect of single mutations and not the mechanism underlying the co-evolution of mutations,” said the paper’s corresponding author Krishna Mallela, PhD, professor in the department of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences located on the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

“Our study helps explain the concept of convergent evolution by balancing positive and negative selection pressures,” he adds.

The cover of Biochemistry. Convergent evolution of multiple mutations enhances SARS-CoV-2 viral fitness by balancing positive and negative selection and improves the chances of selection of mutations together. Credit: Biochemistry

The new paper, co-authored by Vaibhav Upadhyay, Casey Patrick, and Alexandra Lucas from Mallela’s lab, was featured on the journal’s cover. The paper provides the physical basis for why approved antibody therapeutics are not working in neutralizing the recent variants of concern, such as Omicron and its subvariants.

“Understanding the mechanisms underlying the antibody escape and the location of mutations in the spike protein will help in developing new antibody therapeutics that will work against new variants by targeting epitopes with minimal mutations or developing broad neutralizing antibodies that target multiple epitopes,” said Mallela.

“As SARS-CoV-2 has evolved from Alpha to Omicron, more and more mutations are accumulating. We hope that by providing research that understands the role of these mutations, we can help further propel research and the development of new therapies to better combat new variants.” — Krishna Mallela, PhD

The study found that certain mutations appear repeatedly in emerging variants showing convergent evolution. One such evolution occurs at three amino acid positions K417, E484 and N501 in the spike protein’s receptor binding domain (RBD). Nearly half of 4.3 million variant sequences in GISAID database that contain any of these three mutations have all three occurring together. Although individual mutations have both beneficial and deleterious/adverse effects, when they come together, deleterious/adverse effects get canceled out, leading to improved selection of the mutations together.

The researchers examined the physical mechanisms underlying the convergent evolution of the three mutations by delineating the individual and collective effects of mutations on binding to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor, immune escape from neutralizing antibodies, protein stability and expression.

They found the three RBD mutations perform very distinct and specific roles that contribute toward improving the virus fitness and build the case for their positive selection, even though individual mutations have deleterious effects that make them prone to negative selection. Compared to the wild-type, K417T escapes Class 1 antibodies and has increased stability and expression; however, it has decreased ACE2 receptor binding. E484K escapes Class 2 antibodies; however, it has decreased receptor binding, stability, and expression. N501Y increases receptor binding; however, it has decreased stability and expression. When these mutations come together, the deleterious effects are mitigated due to the presence of compensatory effects. Triple mutant K417T/E484K/N501Y has increased ACE2 receptor binding, escapes both Class 1 and Class 2 antibodies, and has similar stability and expression as that of the wild-type.

The authors conclude the collective effect of these mutations is far more advantageous for virus fitness than the individual mutations and the presence of multiple mutations improves the selection of individual mutations.

Mallela concludes, “As SARS-CoV-2 has evolved from Alpha to Omicron, more and more mutations are accumulating. We hope that by providing research that understands the role of these mutations, we can help further propel research and the development of new therapies to better combat new variants.”

Reference: “Convergent Evolution of Multiple Mutations Improves the Viral Fitness of SARS-CoV-2 Variants by Balancing Positive and Negative Selection” by Vaibhav Upadhyay, Casey Patrick, Alexandra Lucas and Krishna M. G. Mallela, 5 May 2022, Biochemistry.

DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00132

This article notes that the variants have different spikes and our vaccines are rather spike-specific. The real problem is within the virus shell, not in the spikes. The virus inside the shell has nucleotide strings that match important parts of human tRNA, one of the few components that can enter the cell nucleus. Getting into the nucleus is how the virus may depress our immune system, letting the virus run rampant. More specifics can be found in the YouTube, “Coronavirus – Using Your DNA Against You”