Researchers have found that climate change-induced ocean acidification is impacting the sense of smell of Dungeness crabs, an economically significant marine species. The research shows that the crabs physically sniff less, have a reduced ability to detect food odors, and exhibit decreased activity in the sensory nerves responsible for smell. This is the first study to investigate the physiological effects of ocean acidification on crabs’ sense of smell, and it could partially explain the decline in their populations. As crabs rely heavily on their sense of smell for finding food, mates, and suitable habitats, this reduced ability to detect odors may have far-reaching consequences for the species and the wider marine ecosystem.

A University of Toronto Scarborough study reveals that ocean acidification, caused by climate change, impairs the sense of smell of economically important Dungeness crabs. This finding could partially explain the decline in their populations and may have significant consequences for the marine ecosystem.

A new University of Toronto Scarborough study finds that climate change is causing a commercially significant marine crab to lose its sense of smell, which could partially explain why their populations are thinning.

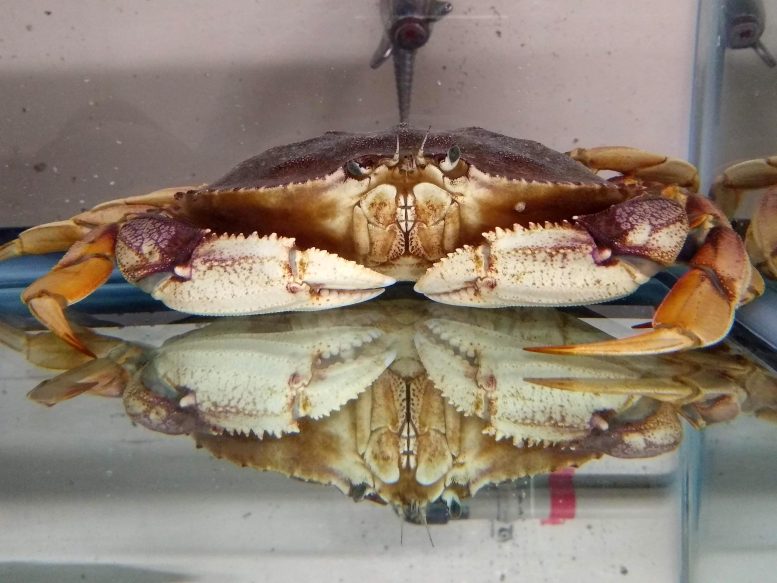

The research was done on Dungeness crabs and found that ocean acidification causes them to physically sniff less, impacts their ability to detect food odors, and even decreases activity in the sensory nerves responsible for smell.

“This is the first study to look at the physiological effects of ocean acidification on the sense of smell in crabs,” says Cosima Porteus, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at U of T Scarborough and co-author of the study along with postdoc Andrea Durant.

Ocean acidification is the result of the Earth’s oceans becoming more acidic due to absorbing increasing amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. It’s a direct consequence of burning fossil fuels and carbon pollution, and several studies have shown it’s having an impact on the behavior of marine wildlife.

Dungeness crabs are an economically important species found along the Pacific coast, stretching from California to Alaska. They are one of the most popular crabs to eat and their fishery was valued at more than $250 million in 2019.

Recent research conducted at U of T Scarborough found that ocean acidification is causing Dungeness crabs to sniff less, affecting their ability to detect food odors. Credit: Cosima Porteus

Like most crabs, they have poor vision, so their sense of smell is crucial in finding food, mates, suitable habitats, and avoiding predators, explains Porteus. They sniff through a process known as flicking, where they flick their antennules (small antenna) through the water to detect odors. Tiny neurons responsible for smell are located inside these antennules, which send electrical signals to the brain.

The researchers discovered two things when the crabs were exposed to ocean acidification: they were flicking less and their sensory neurons were 50 percent less responsive to odors.

“Crabs increase their flicking rate when they detect an odor they are interested in, but in crabs that were exposed to ocean acidification, the odor had to be 10 times more concentrated before we saw an increase in flicking,” says Porteus.

There are a few potential reasons why ocean acidification seems to be impacting the sense of smell in crabs. Porteus points to other research done at the University of Hull that showed ocean acidification disrupts odor molecules, which can impact how they bind to smell receptors in marine animals such as crabs.

For this study, published today (May 9) in the journal Global Change Biology, Porteus and Durant were able to test the electrical activity in the crabs’ sensory neurons to determine they were less responsive to odors. They also discovered that they had fewer receptors and their sensory neurons were physically shrinking by as much as 25 percent in volume.

“These are active cells and if they aren’t detecting odors as much, they might be shrinking to conserve energy. It’s like a muscle that will shrink if you don’t use it,” she says.

Porteus says reduced food detection could have implications for other economically important species such as Alaskan king and snow crabs because their sense of smell functions the same way.

“Losing their sense of smell seems to be climate-related, so this might partially explain some of the decline in their numbers,” says Porteus.

“If crabs are having trouble finding food, it stands to reason females won’t have as much energy to produce eggs.”

Reference: “Ocean acidification alters foraging behaviour in Dungeness crab through impairment of the olfactory pathway” by Andrea Durant, Elissa Khodikian and Cosima S. Porteus, 9 May 2023, Global Change Biology.

DOI: 10.1111/gcb.16738

This research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Some of the analysis was performed at U of T’s Centre for the Neurobiology of Stress.

“… study reveals that ocean acidification, caused by climate change, impairs the sense of smell of economically important Dungeness crabs.”

Strictly speaking, if the ‘acidification’ is CAUSED by climate change, then the anthropogenic emissions of CO2 are not directly responsible. Instead, they seem to be arguing that climate change itself is the driver of acidification, and not increasing emissions.

The unstated assumption is that a systematic reduction in pH is occurring in the Dungeness crab environment. There are no numbers presented in the press release to support this, and the DOI link is not working.

In the real world, ocean salinity and pH have wide variations, both daily and seasonally, particularly in surface waters subject to evaporation, and in coastal waters where rivers and streams bring in water that is commonly alkaline and often has an increased sediment load and fertilizer runoff.

The claimed so-called acidification process is NOT supported by historical observation. The historical measurements were discarded as being unsuitable for purpose, and a model was created that back-predicted that the former open-ocean had a pH of about 8.2. It is currently about 8.1 for the open ocean, and from that, alarmists have predicted that the oceans are experiencing a long-term decline in pH that will lead to acidic water. This is complicated by up-welling waters, such as are monitored at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, where rapid and widely varying pH has been documented in water coming up from the Monterey Bay Submarine Canyon.

It appears that the authors performed an experiment with crabs, but the press release doesn’t say whether they acidified the observation containers with a strong acid (hydrochloric) or a weak acid (carbonic), which past experiments have shown to be an important consideration. They also don’t specify the pH at which the claimed response was observed, and whether it was a step response or a continuous linear response. My suspicion is that if the pH gets outside (high or low) the normal environment, aberrant behavior will be observed. One then needs to make the case that such extreme ranges are actually occurring. That means field work, not just lab experiments.

They don’t seem to be considering other possibilities for the decline in the crab population, such as over-fishing, or decline in food from pollution or temperature changes.

http://wattsupwiththat.com/2015/09/15/are-the-oceans-becoming-more-acidic/