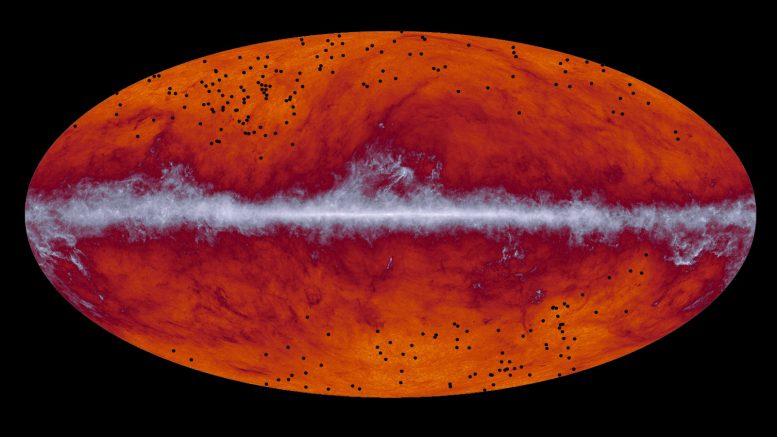

This map of the entire sky was captured by the European Space Agency’s Planck mission. The band running through the middle corresponds to dust in our Milky Way galaxy. The black dots indicate the location of galaxy cluster candidates identified by Planck and subsequently observed by the European Space Agency’s Herschel mission. Credit: ESA and the Planck Collaboration

By using data from ESA’s Herschel and Planck space observatories, astronomers have discovered what could be the precursors of the vast clusters of galaxies that we see today.

One telescope finds the treasure chest, and the other narrows in on the gold coins. Data from two European Space Telescope missions, Planck and Herschel, have together identified some of the oldest and rarest clusters of galaxies in the distant cosmos. Planck’s all-sky images revealed the clumps of bright galaxies, while Herschel data allowed researchers to inspect the galactic gems more closely and confirm the discovery.

NASA played a key role in the Planck and Herschel missions. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, helped develop science instruments and process data for both missions, which ended, as planned, in 2013. The findings appear April 2 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“Finding so many intensely star-forming, dust galaxies in such concentrated groups was a huge surprise,” said Hervé Dole, lead author of the report from the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale in France. “We think this is a missing piece of cosmological structure formation.”

Stars and galaxies sprung to life in the early universe, only later assembling into large clusters. Once the clusters formed, massive amounts of matter collapsed under the influence of gravity, triggering the formation of new stars and galaxies. Dark matter — an enigmatic substance far outweighing “normal” matter in the universe — was intermingled with the stars and galaxies, and helped usher along the process of creating stars. But how these large clusters were ultimately assembled and grew is still a mystery.

The new findings offer astronomers a portal back to this early time, about 10 to 11 billion light-years ago. About 200 candidate objects were identified, many of which were magnified by other galaxies lying in front of them via a process called gravitational lensing.

To find the galactic gems, the astronomers first mined the Planck all-sky maps, looking for the most luminous distant sources of light in the submillimeter-wavelength range. Herschel data, which sees submillimeter and far-infrared light, were then used to home in on the targets. The results showed that some of the objects were bright, young galaxies that had been gravitationally lensed, and others were clusters of galaxies churning out new stars.

According to the science team, there is still more treasure to dig up.

“Even when we combined the powerful capabilities of Planck and Herschel, we were only scratching the surface of the phenomena taking place at this critical era in the history of our universe, when stars, galaxies, and clusters seem to be forming simultaneously,” said George Helou, director of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “That’s one of the reasons this finding is exciting. It shows us that there is so much more to be learned.”

This study also included data from the Infrared Astronomical Satellite, a former project of the U.S., United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. The Infrared Processing and Analysis Center is the NASA-designated archive center for infrared astronomy missions, including the Infrared Astronomical Satellite, Planck, and some Herschel data.

Reference: “Planck intermediate results. XXVII. High-redshift infrared galaxy overdensity candidates and lensed sources discovered by Planck and confirmed by Herschel-SPIRE” by N. Aghanim, B. Altieri, M. Arnaud, M. Ashdown, J. Aumont, C. Baccigalupi, A. J. Banday, R. B. Barreiro, N. Bartolo, E. Battaner, A. Beelen, K. Benabed, A. Benoit-Lévy, J.-P. Bernard, M. Bersanelli, M. Bethermin, P. Bielewicz, L. Bonavera, J. R. Bond, J. Borrill, F. R. Bouchet, F. Boulanger, C. Burigana, E. Calabrese, R. Canameras, J.-F. Cardoso, A. Catalano, A. Chamballu, R.-R. Chary, H. C. Chiang, P. R. Christensen, D. L. Clements, S. Colombi, F. Couchot, B. P. Crill, A. Curto, L. Danese, K. Dassas, R. D. Davies, R. J. Davis, P. de Bernardis, A. de Rosa, G. de Zotti, J. Delabrouille, J. M. Diego, H. Dole, S. Donzelli, O. Doré, M. Douspis, A. Ducout, X. Dupac, G. Efstathiou, F. Elsner, T. A. Enßlin, E. Falgarone, I. Flores-Cacho, O. Forni, M. Frailis, A. A. Fraisse, E. Franceschi, A. Frejsel, B. Frye, S. Galeotta, S. Galli, K. Ganga, M. Giard, E. Gjerløw, J. González-Nuevo, K. M. Górski, A. Gregorio, A. Gruppuso, D. Guéry, F. K. Hansen, D. Hanson, D. L. Harrison, G. Helou, C. Hernández-Monteagudo, S. R. Hildebrandt, E. Hivon, M. Hobson, W. A. Holmes, W. Hovest, K. M. Huffenberger, G. Hurier, A. H. Jaffe, T. R. Jaffe, E. Keihänen, R. Keskitalo, T. S. Kisner, R. Kneissl, J. Knoche, M. Kunz, H. Kurki-Suonio, G. Lagache, J.-M. Lamarre, A. Lasenby, M. Lattanzi, C. R. Lawrence, E. Le Floc’h, R. Leonardi, F. Levrier, M. Liguori, P. B. Lilje, M. Linden-Vørnle, M. López-Caniego, P. M. Lubin, J. F. Macías-Pérez, T. MacKenzie, B. Maffei, N. Mandolesi, M. Maris, P. G. Martin, C. Martinache, E. Martínez-González, S. Masi, S. Matarrese, P. Mazzotta, A. Melchiorri, A. Mennella, M. Migliaccio, A. Moneti, L. Montier, G. Morgante, D. Mortlock, D. Munshi, J. A. Murphy, P. Natoli, M. Negrello, N. P. H. Nesvadba, D. Novikov, I. Novikov, A. Omont, L. Pagano, F. Pajot, F. Pasian, O. Perdereau, L. Perotto, F. Perrotta, V. Pettorino, F. Piacentini, M. Piat, S. Plaszczynski, E. Pointecouteau, G. Polenta, L. Popa, G. W. Pratt, S. Prunet, J.-L. Puget, J. P. Rachen, W. T. Reach, M. Reinecke, M. Remazeilles, C. Renault, I. Ristorcelli, G. Rocha, G. Roudier, B. Rusholme, M. Sandri, D. Santos, G. Savini, D. Scott, L. D. Spencer, V. Stolyarov, R. Sunyaev, D. Sutton, J.-F. Sygnet, J. A. Tauber, L. Terenzi, L. Toffolatti, M. Tomasi, M. Tristram, M. Tucci, G. Umana, L. Valenziano, J. Valiviita, I. Valtchanov, B. Van Tent, J. D. Vieira, P. Vielva, L. A. Wade, B. D. Wandelt, I. K. Wehus, N. Welikala, A. Zacchei and A. Zonca, 30 September 2015, Astronomy & Astrophysics.

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201424790

arXiv: 1503.08773

What the hay, I’m not doing anything, so this’s for what it’s worth. I hate science writing like this. This’s intended as constructive criticism, fwiw.

Start with the caption of the photo at the top. That caption means nothing to me. It doesn’t tell me what direction I’m looking at, nor tell me what I’m seeing. Either I’m looking at the Milky Way, or I’m looking away from our galactic centre. Which is it?

The writing then carries on from an equally shallow plane. So many articles I’ve read attempt to find some meaning in the distribution of galaxy groups. What’s wrong with random? Dump a bag of marbles, and there they are. What are you really trying to see here? God? You never explain what is the real problem you think you’re looking at. What?!? So what if you’ve detected a honking big wall of galaxies over there. What’s that mean to you? To me, it means nothing or at best a random distribution. Can you say the numbers confirm otherwise?

“10 to 11 billion light-years ago”? What?

That’s like answering the question “When did you last have a date?” with:

“Oh, about 250,000 kilometres ago.”

Weird.