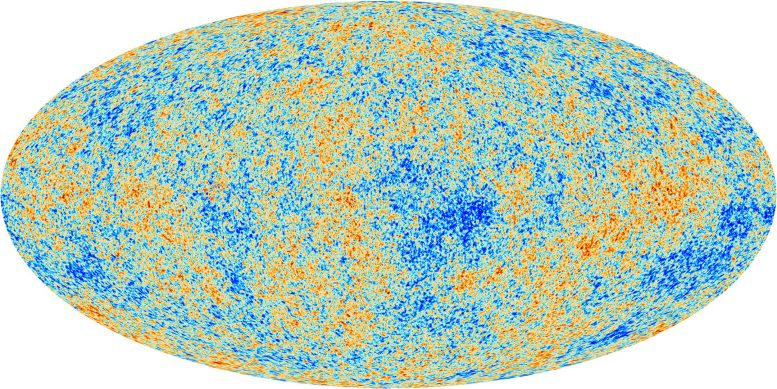

The Planck satellite mission mapped light temperature differences on the oldest surface known — the background sky left billions of years ago when our universe first became transparent to light. Those differences helped to recreate the sound of the Big Bang. Credit: ESA and the Planck Collaboration

Using new data from the ESA’s Planck Mission analysis of the CMB, physicist John Cramer from the University of Washington provides a new “high-fidelity” rendition of the Sound of the Big Bang.

A decade ago, spurred by a question for a fifth-grade science project, University of Washington physicist John Cramer devised an audio recreation of the Big Bang that started our universe nearly 14 billion years ago.

Now, armed with more sophisticated data from a satellite mission observing the cosmic microwave background – a faint glow in the universe that acts as sort of a fossilized fingerprint of the Big Bang – Cramer has produced new recordings that fill in higher frequencies to create a fuller and richer sound. (The sound files run from 20 seconds to a little longer than 8 minutes.)

The effect is similar to what seismologists describe as a magnitude 9 earthquake causing the entire planet to actually ring. In this case, however, the ringing covered the entire universe – before it grew to such gargantuan proportions.

“Space-time itself is ringing when the universe is sufficiently small,” Cramer said.

In 2001, Cramer wrote a science-based column for Analog Science Fiction & Fact magazine describing the likely sound of the Big Bang based on cosmic microwave background radiation observations taken from balloon experiments and satellites.

A couple of years later that article prompted a question from a mother in Pennsylvania whose 11-year-old son was working on a project about the Big Bang: Is the sound of the Big Bang actually recorded anywhere?

Cramer answered that it wasn’t – but then began thinking that it could be. He used data from the cosmic microwave background on temperature fluctuations in the very early universe. The data on those wavelength changes were fed into a computer program called Mathematica, which converted them to sound. A 100-second recording represents the sound from about 380,000 years after the Big Bang until about 760,000 years after the Big Bang.

“The original sound waves were not temperature variations, though, but were real sound waves propagating around the universe,” he said.

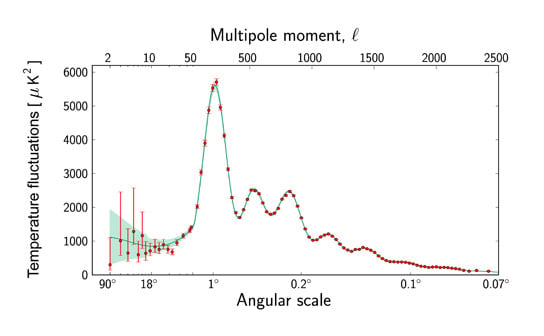

Cramer noted, however, that the 2003 data lacked high-frequency structure. More complete data were recently gathered by an international collaboration using the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite mission, which has detectors so sensitive that they can distinguish temperature variations of a few millionths of a degree in the cosmic microwave background. That data were released in late March and led to the new recordings.

Credit: Planck Multipole Spectrum

As the universe cooled and expanded, it stretched the wavelengths to create “more of a bass instrument,” Cramer said. The sound gets lower as the wavelengths are stretched farther, and at first it gets louder but then gradually fades. The sound was, in fact, so “bass” that he had to boost the frequency 100 septillion times (that’s a 100 followed by 24 more zeroes) just to get the recordings into a range where they can be heard by humans.

Cramer is a UW physics professor who has been part of a large collaboration studying what the universe might have been like moments after the Big Bang by causing collisions between heavy ions such as gold in the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York.

Creating a sound profile for the Big Bang was something to do on the side, Cramer said.

“It was an interesting thing to do that I wanted to share. It’s another way to look at the work these people are doing,” he said.

If the big bang happens and no one’s around, Etc., Etc.

No one was around and it happened and we able to “hear” the sounds, thanks to the collaboration of many scientists! At least that is my humble interpretation.

The sound of the Big Bang, Planck’s version 2013, says prof.Cramer of Washington University, that the original Big Bang waves to the order of a fraction of the Universe size , which should be with very very low frequency

multiplied by 100 septillion times comes to give an audible level of human ears gives this sound. If there is an atomic explosion on Moon, you cannot hear it on Earth and can see only its light effect. Actual sound waves cannot travel in vacuum and there is no point in calling this as sound heard while Big Bang was going on 14 billion years ago. It is only a mathematical plotting in a frequency graph and enjoying its sound in computer. Thank You.

Perhaps thinking Big Bang as an explosion is incorrect from the start. I am more inclined to think it as a Higgs boson field transition from a higher energy state to lower and propagating through the Universe and causing effects we still see today. It would explain rapid expansion of the early Universe better than elaborate Inflation theory. Purely a personal believe: Universe was there before this so-called ”Big Bang”, but it was very different.