A new research study has revealed the most intense heatwaves ever across the world – and remarkably some of these went almost unnoticed decades ago.

The research, led by the University of Bristol, also shows heatwaves are projected to get hotter in the future as climate change worsens.

The western North America heatwave last summer was record-breaking with an all-time Canadian high of 49.6 °C (121.3 °F) in Lytton, British Columbia, on June 29, an increase of 4.6 °C (8.3 °F) from the previous peak.

The new findings, published on May 4, 2022, in the journal Science Advances, uncovered five other heatwaves around the world which were even more severe, but went largely underreported.

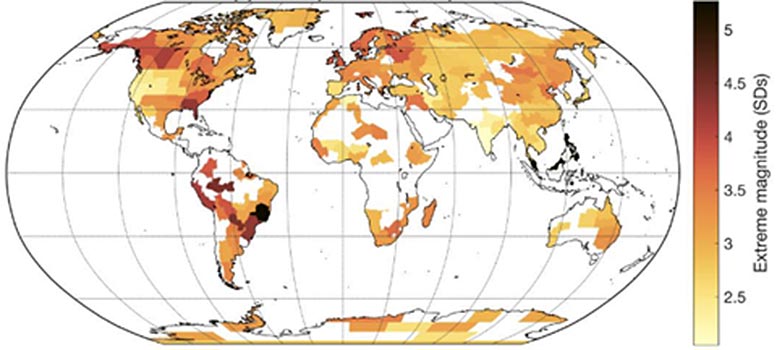

Map showing the magnitude of the greatest extreme since 1950 in each region, expressed in terms of deviation from average temperatures, with climate change trend removed. Darker colors indicate greater extremes. Credit: University of Bristol

Lead author, climate scientist Dr. Vikki Thompson at the University of Bristol, said: “The recent heatwave in Canada and the United States shocked the world. Yet we show there have been some even greater extremes in the last few decades. Using climate models, we also find extreme heat events are likely to increase in magnitude over the coming century – at the same rate as the local average temperature.”

Heatwaves are one of the most devastating extreme weather events. The western North America heatwave was the most deadly weather event ever in Canada, resulting in hundreds of fatalities. The associated raging wildfires also led to extensive infrastructure damage and loss of crops.

But the study, which calculated how extreme heatwaves were relative to the local temperature, showed the top three hottest-ever in the respective regions were in Southeast Asia in April 1998, which hit 32.8 °C (91.0 °F), Brazil in November 1985, peaking at 36.5 °C (97.7 °F), and Southern USA in July 1980, when temperatures rose to 38.4 °C (101.1 °F).

Dr. Vikki Thompson, from the university’s Cabot Institute for the Environment, said: “The western North America heatwave will be remembered because of its widespread devastation. However, the study exposes several greater meteorological extremes in recent decades, some of which went largely under the radar likely due to their occurrence in more deprived countries. It is important to assess the severity of heatwaves in terms of local temperature variability because both humans and the natural eco-system will adapt to this, so in regions where there is less variation, a smaller absolute extreme may have more harmful effects.”

The team of scientists also used sophisticated climate model projections to anticipate heatwave trends for the rest of this century. The modeling indicated levels of heatwave intensity are set to rise in line with increasing global temperatures.

Although the highest local temperatures do not necessarily cause the biggest impacts, they are often related. Improving understanding of climate extremes and where they have occurred can help prioritize measures to help tackle this in the most vulnerable regions.

Co-author Professor Dann Mitchell, Professor in Climate Sciences at the University of Bristol, said: “Climate change is one of the greatest global health problems of our time, and we have shown that many heatwaves outside of the developed world have gone largely unnoticed. The country-level burden of heat on mortality can be in the thousands of deaths, and countries which experience temperatures outside their normal range are the most susceptible to these shocks.”

In recognition of the dangerous consequences of climate change and a clear commitment to help tackle this, in 2019 the University of Bristol became the first UK university to declare a climate emergency.

Reference: “The 2021 western North America heat wave among the most extreme events ever recorded globally” by Vikki Thompson, Alan T. Kennedy-Asser, Emily Vosper, Y. T. Eunice Lo, Chris Huntingford, Oliver Andrews, Matthew Collins, Gabrielle C. Hegerl and Dann Mitchell, 4 May 2022, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abm6860

“Using climate models, we also find extreme heat events are likely to increase in magnitude over the coming century – at the same rate as the local average temperature.”

These “sophisticated” climate models need to be tested against reality before their predictions can be trusted. There is an old adage that “All non-trivial computer programs have bugs. All potentially useful programs are non-trivial.”

They didn’t go back far enough to catch the North American heat waves of the 1930s. Average annual global temperatures were flat to declining until the end of the 1970s. However, some of their record heat waves occurred before global temperatures started to rise. That brings into question their assertion, “The modeling indicated levels of heatwave intensity are set to rise in line with increasing global temperatures.”

Empirical data trumps model outputs. I have shown that there is no empirical evidence to support increasing severity or frequency of global heatwaves in recent decades, despite increasing global temperatures.

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2019/09/06/the-gestalt-of-heat-waves/

They speculate that soil moisture played an important role in the Canadian heat wave. Therefore, they should have used a soil map, or as a proxy, the Köppen climate classification for the region of the heat wave. Instead, they used the blunt axe approach of a simple, convenient box. Had they used a detailed soil map, they could have perhaps shed light on the probability of their conjecture that soil moisture played an important role.

https://www.britannica.com/science/Koppen-climate-classification

Incidentally, all the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phases have run warm, with CMIP6, which they used, running the warmest of the lot. This should give readers further pause in accepting the claims.

They remark in their article, “Extreme events, by their very definition, occur infrequently.” This is all the more reason to look back more than 70 years, which only defines the equivalent of two climate periods.

My assessment it that they were anxious to publish something that was novel, without really thinking through the design to be sure that what they ended up with was reliable.