Newly created strontium, an element used in fireworks, detected in space for the first time following observations with ESO telescope.

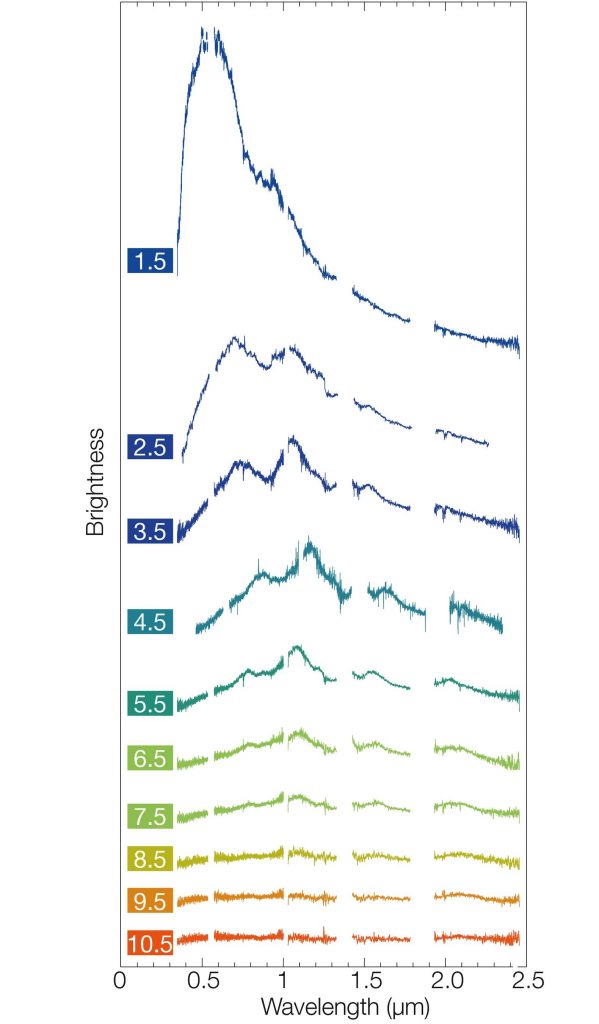

This montage of spectra taken using the X-shooter instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope shows the changing behavior of the kilonova in the galaxy NGC 4993 over a period of 12 days after the explosion was detected on August 17, 2017. Each spectrum covers a range of wavelengths from the near-ultraviolet to the near-infrared and reveals how the object became dramatically redder as it faded. Credit: ESO/E. Pian et al./S. Smartt & ePESSTO

For the first time, a freshly made heavy element, strontium, has been detected in space, in the aftermath of a merger of two neutron stars. This finding was observed by ESO’s X-shooter spectrograph on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and is published on October 23, 2019, in Nature. The detection confirms that the heavier elements in the Universe can form in neutron star mergers, providing a missing piece of the puzzle of chemical element formation.

In 2017, following the detection of gravitational waves passing the Earth, ESO pointed its telescopes in Chile, including the VLT, to the source: a neutron star merger named GW170817. Astronomers suspected that, if heavier elements did form in neutron star collisions, signatures of those elements could be detected in kilonovae, the explosive aftermaths of these mergers. This is what a team of European researchers has now done, using data from the X-shooter instrument on ESO’s VLT.

Following the GW170817 merger, ESO’s fleet of telescopes began monitoring the emerging kilonova explosion over a wide range of wavelengths. X-shooter in particular took a series of spectra from the ultraviolet to the near-infrared. Initial analysis of these spectra suggested the presence of heavy elements in the kilonova, but astronomers could not pinpoint individual elements until now.

“By reanalyzing the 2017 data from the merger, we have now identified the signature of one heavy element in this fireball, strontium, proving that the collision of neutron stars creates this element in the Universe,” says the study’s lead author Darach Watson from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. On Earth, strontium is found naturally in the soil and is concentrated in certain minerals. Its salts are used to give fireworks a brilliant red color.

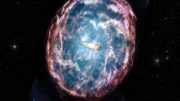

Newly created strontium, an element used in fireworks, has been detected in space for the first time following observations with ESO’s Very Large Telescope. The detection confirms that the heavier elements in the Universe can form in neutron star mergers, providing a missing piece of the puzzle of chemical element formation. Credit: ESO

Astronomers have known the physical processes that create the elements since the 1950s. Over the following decades, they have uncovered the cosmic sites of each of these major nuclear forges, except one. “This is the final stage of a decades-long chase to pin down the origin of the elements,” says Watson. “We know now that the processes that created the elements happened mostly in ordinary stars, in supernova explosions, or in the outer layers of old stars. But, until now, we did not know the location of the final, undiscovered process, known as rapid neutron capture, that created the heavier elements in the periodic table.”

Rapid neutron capture is a process in which an atomic nucleus captures neutrons quickly enough to allow very heavy elements to be created. Although many elements are produced in the cores of stars, creating elements heavier than iron, such as strontium, requires even hotter environments with lots of free neutrons. Rapid neutron capture only occurs naturally in extreme environments where atoms are bombarded by vast numbers of neutrons.

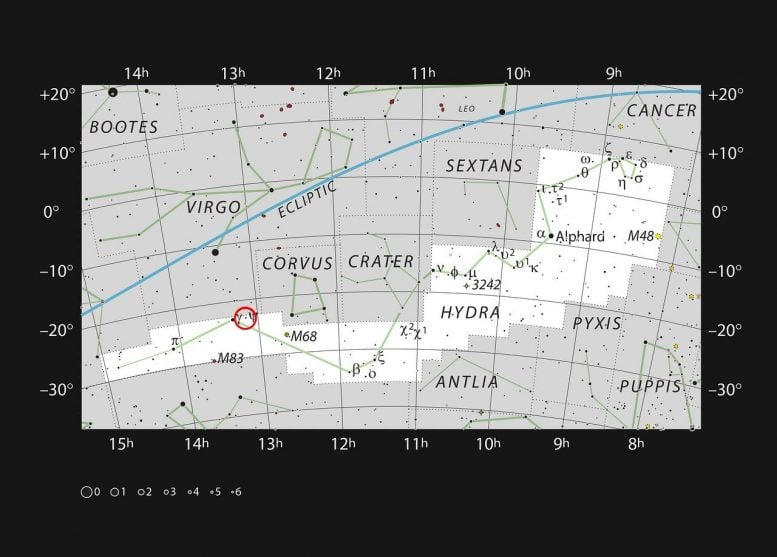

This chart shows the sprawling constellation of Hydra (The Female Sea Serpent), the largest and longest constellation in the sky. Most stars visible to the naked eye on a clear dark night are shown. The red circle marks the position of the galaxy NGC 4993, which became famous in August 2017 as the site of the first gravitational wave source that was also identified in light visible light as the kilonova GW170817. NGC 4993 can be seen as a very faint patch with a larger amateur telescope. Credit: ESO, IAU and Sky & Telescope

“This is the first time that we can directly associate newly created material formed via neutron capture with a neutron star merger, confirming that neutron stars are made of neutrons and tying the long-debated rapid neutron capture process to such mergers,” says Camilla Juul Hansen from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, who played a major role in the study.

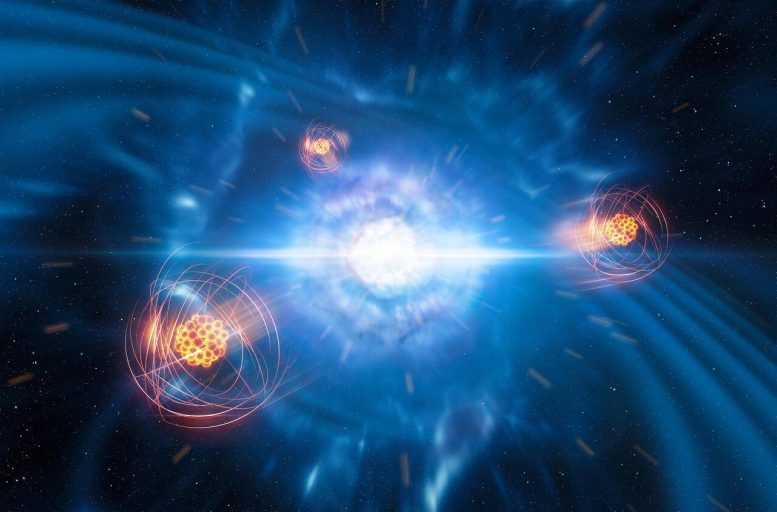

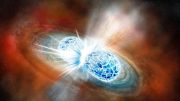

This artist’s impression shows two tiny but very dense neutron stars merging and exploding as a kilonova. Such objects are the main source of very heavy chemical elements, such as gold and platinum, in the Universe. The detection of one element, strontium (Sr), has now been confirmed using data from the X-shooter instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

Scientists are only now starting to better understand neutron star mergers and kilonovae. Because of the limited understanding of these new phenomena and other complexities in the spectra that the VLT’s X-shooter took of the explosion, astronomers had not been able to identify individual elements until now.

This wide-field image generated from the Digitized Sky Survey 2 shows the sky around the galaxy NGC 4993. This galaxy was the host to a merger between two neutron stars, which led to a gravitational wave detection, a short gamma-ray burst, and an optical identification of a kilonova event. Credit: ESO and Digitized Sky Survey 2

“We actually came up with the idea that we might be seeing strontium quite quickly after the event. However, showing that this was demonstrably the case turned out to be very difficult. This difficulty was due to our highly incomplete knowledge of the spectral appearance of the heavier elements in the periodic table,” says University of Copenhagen researcher Jonatan Selsing, who was a key author on the paper.

This animation is based on a series of spectra of the kilonova in NGC 4993 observed by the X-shooter instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. They cover a period of 12 days after the initial explosion on 17 August 2017. The kilonova is very blue initially but then brightens in the red and fades. Credit: ESO/E. Pian et al./S. Smartt & ePESSTO/L. Calçada

The GW170817 merger was the fifth detection of gravitational waves, made possible thanks to the NSF’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the US and the Virgo Interferometer in Italy. Located in the galaxy NGC 4993, the merger was the first, and so far the only, gravitational wave source to have its visible counterpart detected by telescopes on Earth.

With the combined efforts of LIGO, Virgo, and the VLT, we have the clearest understanding yet of the inner workings of neutron stars and their explosive mergers.

This research was presented in a paper published in Nature on October 23, 2019.

Reference: “Identification of strontium in the merger of two neutron stars” by Darach Watson, Camilla J. Hansen, Jonatan Selsing, Andreas Koch, Daniele B. Malesani, Anja C. Andersen, Johan P. U. Fynbo, Almudena Arcones, Andreas Bauswein, Stefano Covino, Aniello Grado, Kasper E. Heintz, Leslie Hunt, Chryssa Kouveliotou, Giorgos Leloudas, Andrew J. Levan, Paolo Mazzali and Elena Pian, 23 October 2019, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1676-3

PDF

The team is composed of D. Watson (Niels Bohr Institute & Cosmic Dawn Center, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), C. J. Hansen (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany), J. Selsing (Niels Bohr Institute & Cosmic Dawn Center, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), A. Koch (Center for Astronomy of Heidelberg University, Germany), D. B. Malesani (DTU Space, National Space Institute, Technical University of Denmark, & Niels Bohr Institute & Cosmic Dawn Center, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), A. C. Andersen (Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), J. P. U. Fynbo (Niels Bohr Institute & Cosmic Dawn Center, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), A. Arcones (Institute of Nuclear Physics, Technical University of Darmstadt, Germany & GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung, Darmstadt, Germany), A. Bauswein (GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung, Darmstadt, Germany & Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies, Germany), S. Covino (Astronomical Observatory of Brera, INAF, Milan, Italy), A. Grado (Capodimonte Astronomical Observatory, INAF, Naples, Italy), K. E. Heintz (Center for Astrophysics and Cosmology, Science Institute, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland & Niels Bohr Institute & Cosmic Dawn Center, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), L. Hunt (Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory, INAF, Florence, Italy), C. Kouveliotou (George Washington University, Physics Department, Washington DC, USA & Astronomy, Physics and Statistics Institute of Sciences), G. Leloudas (DTU Space, National Space Institute, Technical University of Denmark, & Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), A. Levan (Department of Physics, University of Warwick, UK), P. Mazzali (Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, UK & Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Garching, Germany), E. Pian (Astrophysics and Space Science Observatory of Bologna, INAF, Bologna, Italy).

Above the news the strengten the signal of cosmic rays can be spectre view of time lapse