For this study, researchers created fruit flies carrying the same genetic mutation that causes the disease.

A new study from scientists at the University of North Carolina suggests that previous assumptions regarding the SMN gene, which is linked with spinal muscular atrophy, are wrong. They found that instead of faulty processing, a separate role of the SMN gene is likely responsible for the disease’s manifestations.

Over 15 years ago, researchers linked a defect in a gene called survival motor neuron – or SMN – with the fatal disease spinal muscular atrophy. Because SMN had a role in assembling the intracellular machinery that processes genetic material, it was assumed that faulty processing was to blame.

Now, University of North Carolina scientists have discovered that this commonly held assumption is wrong and that a separate role of the SMN gene – still not completely elucidated – is likely responsible for the disease’s manifestations. The research was published on Thursday, June 21, 2012, in the journal Cell Reports.

“There are a number of gene therapies and RNA therapies in the pipeline that may still work regardless of the underlying cause of the disease,” said senior study author Gregory Matera, PhD, professor in the departments of biology and genetics and a member of the Program in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology in the UNC School of Medicine.

“But if those approaches don’t pan out, it could be that the therapy isn’t reaching the precise tissues where defective SMN is most damaging,” he added. “Our result is exciting because we now have a starting point to uncover what is truly causing this disease so we can more effectively treat it.”

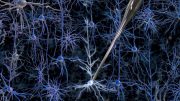

Spinal muscular atrophy is characterized by muscle weakness and wasting (atrophy) resulting from the progressive loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord. The disease is due to a partial loss of function in the SMN gene that normally loads up the “splicing” machinery with the proteins necessary for cutting and pasting the cell’s genetic instructions together. Cells that completely lack SMN fail to correctly generate and process the genetic blueprint for the proteins needed to carry out the rest of the body’s activities.

But in addition to roles in splicing, SMN has been implicated in a number of other processes that occur only in specific tissues, such as the formation of the junction between muscle and nerve cells or the maintenance of muscle architecture. Thus Matera and his colleagues wondered if defective splicing was really responsible for spinal muscular atrophy or if one of these tissue-specific roles was the cause.

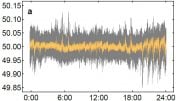

In this study, the researchers investigated whether they could disconnect SMN’s “primary” role in splicing from the physical characteristics typical of spinal muscular atrophy. To do so, they first created fruit flies carrying the same genetic mutation that causes the disease. The mutant flies didn’t survive to the larval stage and showed significant defects in locomotion as well as reductions in those important splicing proteins.

But when the researchers re-introduced functional SMN, only the larval lethality and locomotor defects — not the level of splicing factors –were rescued. Therefore, this splicing function of SMN is not a major contributor to spinal muscular atrophy. Right now Matera and colleagues are using a number of highly sophisticated “–omics” methods such as proteomics and RNomics to pin down the real culprit.

Reference: “A Drosophila Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Uncouples snRNP Biogenesis Functions of Survival Motor Neuron from Locomotion and Viability Defects” by Kavita Praveen, Ying Wen and A. Gregory Matera, 21 June 2012, Cell Reports.

DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.05.014

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. Study co-authors from UNC were Kavita Praveen and Ying Wen.

The initial paragraph of this article is totally wrong. The research paper does not question the well-established link between spinal muscular atrophy and the SMN1/SMN2 genes. This links has been undoubtedly demonstrated in 1995 and is not being debated as far as I am aware of.

What this article brought is unlinking the splicing role of the SMN protein and the disease phenotype. That is, the level of SMN-mediated splicing is not related to the severity of the disease. As the authors have put it, “the observed decreases in snRNA levels in Smn null animals are not major contributors to organismal phenotype.” All this with a silent (but not guaranteed correct) assumption that the genetically modified drosophila cells work in an exactly the same way as cells of SMN patients…

So, to all SMA patients, the link between SMA and SMN-coding genes (SMN1/SMN2) remains. The link between SMA and a certain molecular role of SMN protein is disputed.

Thank you very much for your input. I have revised the paragraph, and hopefully it is more clear now. (We use that initial paragraph to summarize the article in layman’s terms. I believe it was correct to begin with, but unfortunately worded in such a way that a different and incorrect interpretation was possible.)