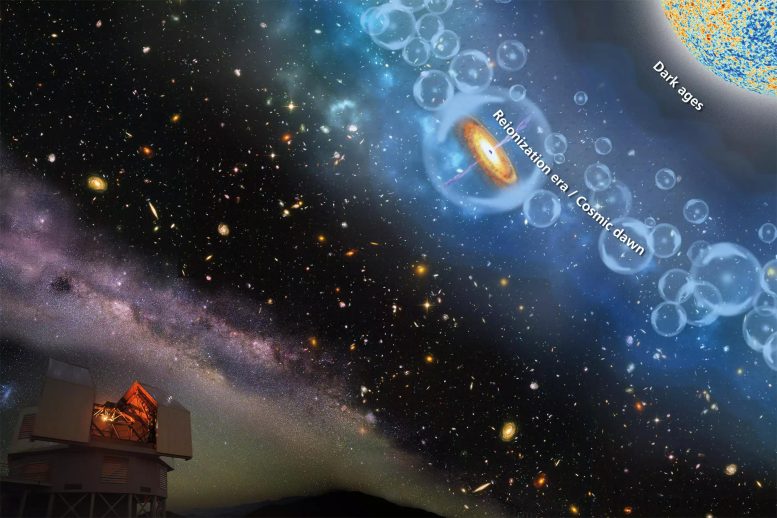

Schematic representation of the view into cosmic history provided by the bright light of distant quasars. Observing with a telescope (bottom left) allows us to gain information about the so-called reionization epoch (“bubbles” top right) that followed the Big Bang phase (top right). Credit: Carnegie Institution for Science / MPIA (annotations)

Astronomers determine the time when all the neutral hydrogen gas between galaxies produced by the Big Bang became fully ionized.

A group of astronomers has robustly timed the end of the epoch of reionization of the neutral hydrogen gas to approximately 1.1 billion years after the Big Bang. Reionization began when the first generation of stars formed after the cosmic “dark ages,” a long period when the Universe was filled with neutral gas alone without any sources of light. The new finding settles a debate that lasted for two decades and follows from the radiation signatures of 67 quasars with imprints of the hydrogen gas the light passed through before it reached Earth. Pinpointing the end of this “cosmic dawn” will help identify the ionizing sources: the first stars and galaxies.

From its inception to its current state, the Universe has undergone different phases. During the first 380,000 years after the Big Bang, it was a hot and dense ionized plasma. It cooled down enough after this period for the protons and electrons that filled the Universe to combine into neutral hydrogen atoms. The Universe had no sources of visible light for the most part during these “dark ages.”

With the advent of the first stars and galaxies roughly 100 million years later, that gas gradually became ionized by the stars’ ultra-violet (UV) radiation again. This process separates the electrons from the protons, leaving them as free particles. This era is commonly known as the “cosmic dawn.” Today, all the hydrogen spread out between galaxies, known as intergalactic gas, is fully ionized. However, when that occurred is a heavily discussed topic among scientists and a highly competitive field of research.

A late end of the cosmic dawn

Now, an international team of astronomers led by Sarah Bosman from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany, has precisely timed the end of the reionization epoch to 1.1 billion years after the Big Bang. “I am fascinated by the idea of the different phases which the Universe went through leading to the formation of the Sun and Earth. It is a great privilege to contribute a new small piece to our knowledge of cosmic history,” says Sarah Bosman. She is the main author of the research article that was recently published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Frederick Davies, also an MPIA astronomer and co-author of the paper, comments, “Until a few years ago, the prevailing wisdom was that reionization completed almost 200 million years earlier. Here we now have the strongest evidence yet that the process ended much later, during a cosmic epoch more readily observable by current generation observational facilities.” This time correction may appear marginal considering the billions of years since the Big Bang. However, a few hundred million years more was sufficient to produce several dozens of stellar generations in the early cosmic evolution. The timing of the “cosmic dawn” era constrains the nature and lifetime of the ionizing sources present during the hundreds of million years it lasted.

This indirect approach is currently the only way to characterize the objects that drove the process of reionization. Observing those first stars and galaxies directly is beyond the capabilities of contemporary telescopes. They are simply too faint to obtain useful data within a reasonable amount of time. Even next-generation facilities like ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) or the James Webb Space Telescope may struggle with such a task.

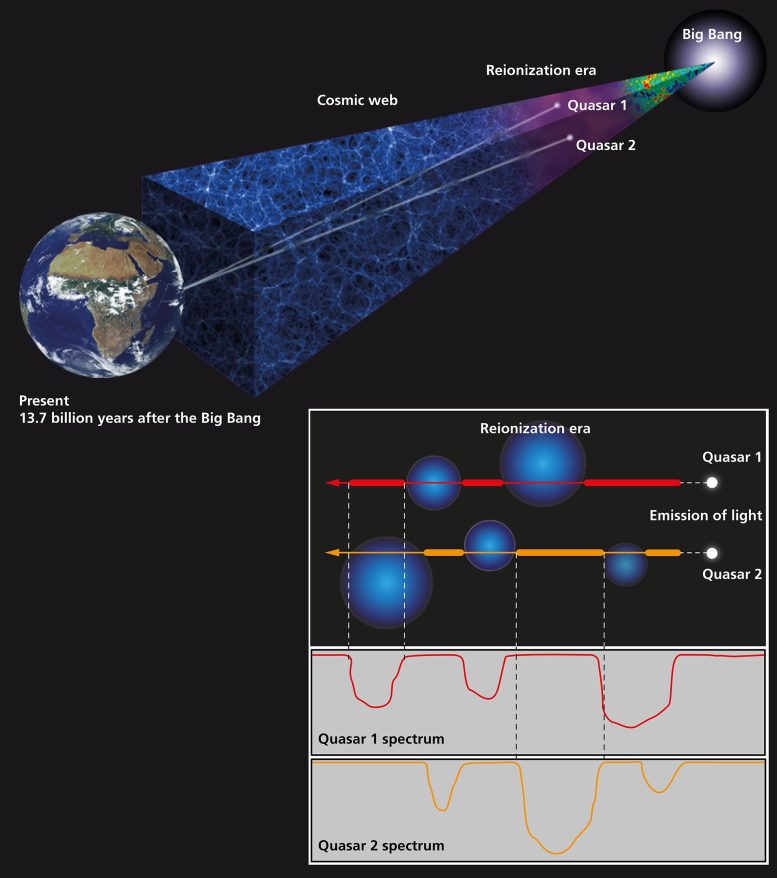

From Earth, we are always looking into the past of the cosmos. The light from distant quasars from the early universe passed through the already partially ionized gas of the reionization epoch, arranged around early galaxies. The neutral hydrogen gas between the galaxies produces the signatures of absorption. Due to the expansion of the Universe, absorption lines appear differently redshifted from the UV range. Credit: MPIA graphics department

Quasars as cosmic probes

To investigate when the Universe was fully ionized, scientists apply different methods. One is to measure the emission of neutral hydrogen gas at the famous 21-centimeter spectral line. Instead, Sarah Bosman and her colleagues analyzed the light received from strong background sources. They employed 67 quasars, the bright disks of hot gas surrounding the central massive black holes in distant active galaxies. Looking at a quasar spectrum, which visualizes its intensity laid out across the observed wavelengths, astronomers find patterns where light seems to be missing. That is what scientists call absorption lines. Neutral hydrogen gas absorbs this portion of light along its journey from the source to the telescope. The spectra of those 67 quasars are of an unprecedented quality, which was crucial for the success of this study.

The method involves looking at a spectral line equivalent to a wavelength of 121.6 nanometers (one nanometer is one-billionth of a meter). This wavelength belongs to the UV range and is the strongest hydrogen spectral line. However, the cosmic expansion shifts the quasar spectrum to longer wavelengths the farther the light travels. Therefore, the redshift of the observed UV absorption line can be translated into the distance from Earth. In this study, the effect had moved the UV line into the infrared range as it reached the telescope.

Depending on the fraction between neutral and ionized hydrogen gas, the degree of absorption, or inversely, the transmission through such a cloud, attains a particular value. When the light encounters a region with a high fraction of ionized gas, it cannot absorb UV radiation that efficiently. This property is what the team was looking for.

The quasar light passes through many hydrogen clouds at different distances on its path, each of them leaving its imprint at smaller redshifts from the UV range. In theory, analyzing the change in transmission per redshifted line should yield the time or distance at which the hydrogen gas was fully ionized

Models help disentangle competing influences

Unfortunately, the circumstances are even more complicated. Since the end of reionization, only the intergalactic space is fully ionized. There is a network of partially neutral matter that connects galaxies and galaxy clusters, called the “cosmic web.” Where the hydrogen gas is neutral, it leaves its mark in the quasar light, too.

To disentangle these influences, the team applied a physical model that reproduces variations measured in a much later epoch when the intergalactic gas was already fully ionized. When they compared the model with their results, they discovered a deviation at a wavelength where the 121.6 nanometers line was shifted by a factor of 5.3 times corresponding to a cosmic age of 1.1 billion years. This transition indicates the time when changes in the measured quasar light become inconsistent with fluctuations from the cosmic web alone. Therefore, that was the latest period when neutral hydrogen gas must have been present in intergalactic space and subsequently became ionized. It was the end of the “cosmic dawn.”

The future is bright

“This new dataset provides a crucial benchmark against which numerical simulations of the Universe’s first billion years will be tested for years to come,” says Frederick Davies. They will help characterize the ionizing sources, the very first generations of stars.

“The most exciting future direction for our work is expanding it to even earlier times, toward the mid-point of the reionization process,” Sarah Bosman points out. “Unfortunately, greater distances mean that those earlier quasars are significantly fainter. Therefore, the expanded collecting area of next-generation telescopes such as the ELT will be crucial.”

Additional information

Of the 67 quasars used in this study, 25 stem from the XQR-30 survey. It is a large observational program of almost 250 hours to obtain high-quality spectra of 30 quasars with the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) X-shooter spectrograph mounted at UT3 of the Very Large Telescope (VLT). XQR-30 is an international cooperation project between 17 institutes across five continents headed by MPIA, INAF in Trieste, Italy (home institute of the Principal Investigator and co-author Valentina D’Odorico), and the University of Swinburne in Australia. X-shooter has been built by a consortium of institutes in Denmark, France, Italy, and The Netherlands together with ESO.

Reference: “Hydrogen reionization ends by z = 5.3: Lyman-a optical depth measured by the XQR-30 sample” by Sarah E I Bosman, Frederick B Davies, George D Becker, Laura C Keating, Rebecca L Davies, Yongda Zhu, Anna-Christina Eilers, Valentina D’Odorico, Fuyan Bian, Manuela Bischetti, Stefano V Cristiani, Xiaohui Fan, Emanuele P Farina, Martin G Haehnelt, Joseph F Hennawi, Girish Kulkarni, Andrei Mesinger, Romain A Meyer, Masafusa Onoue, Andrea Pallottini, Yuxiang Qin, Emma Ryan-Weber, Jan-Torge Schindler, Fabian Walter, Feige Wang and Jinyi Yang, 7 June 2022, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stac1046

The MPIA team consists of Sarah E. I. Bosman, Frederick B. Davies, Romain A. Meyer (MPIA), Masafusa Onoue (now Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Peking University, Beijing, China), Jan-Torge Schindler (now Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, The Netherlands) and Fabian Walter.

Other team members are George D. Becker (Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of California, Riverside, USA [UCR]), Laura C. Keating (Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik, Potsdam, Germany [AIP]), Rebecca L. Davies (Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Australia [CAS] and ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D), Australia [ARC]), Yongda Zhu (UCR), Anna-Christina Eilers (MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, Cambridge, USA), Valentina D’Odorico (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste, Italy [INAF Trieste] and Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, Italy [SNS]), Fuyan Bian (European Southern Observatory, Vitacura, Santiago, Chile [ESO]), Manuela Bischetti (INAF Trieste and INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, Italy), Stefano V. Cristiani (INAF Trieste), Xiaohui Fan (Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA [Steward]), Emanuele P. Farina (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Garching bei München, Germany), Martin G. Haehnelt (Institute of Astronomy and Kavli Institute for Cosmology, University of Cambridge, UK), Joseph F. Hennawi (Department of Physics, Broida Hall, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA and Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, The Netherlands), Girish Kulkarni (Department of Theoretical Physics, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, India), Andrei Mesinger (SNS), Andrea Pallottini (INAF Trieste), Yuxiang Qin (School of Physics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia and ARC), Emma Ryan-Weber (CAS and ARC), Feige Wang (Steward), and Jinyi Yang (Steward).

Be the first to comment on "The End of the Cosmic Dawn: Settling a Two-Decade Debate"