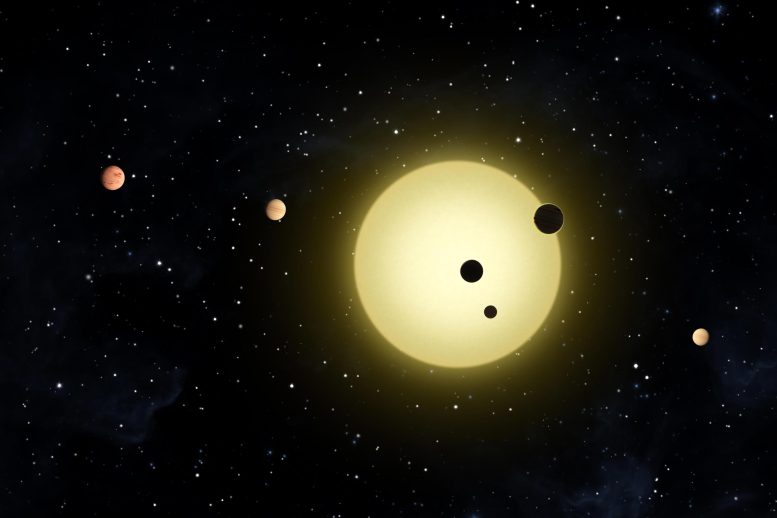

This artistic rendering depicts Kepler-11, which has six stars in tight orbit around it. Daniel Fabrycky, UChicago assistant professor in astronomy & astrophysics, was a member of the team that discovered Kepler-11 in 2009. Credit: Tim Pyle

Aided by technology, astronomers at the University of Chicago search for far-off planets like Earth.

When astronomers discovered planet GJ 1214b circling a star more than 47 light-years from Earth in 2009, their data presented two possibilities: Either it was a mini-Neptune shrouded in a thick atmosphere of hydrogen and helium, or it was a water world nearly three times the size of Earth.

Along came Jacob Bean, now an assistant professor in astronomy & astrophysics at the University of Chicago, who used a new method called multi-object spectroscopy to analyze the planet’s atmosphere from large, ground-based telescopes. Aided by technology, Bean and his colleagues are surmounting the challenge of inferring the atmospheric composition of planets that were invisible to humans just a few years ago.

Asst. Prof. Daniel Fabrycky explains how his work with the Kepler space telescope is helping to find far-off planets like our own. Credit: UChicago Creative

“We’re trying to distinguish whether it’s like the gas giants we know about, or something fundamentally different from what we’ve seen in our solar system — an atmosphere predominantly composed of water,” Bean says.

The search for exoplanets—planets beyond our own solar system—has taken off over the last decade, and is now a growing component of UChicago’s research agenda in astronomy. One estimate published in January calculated that our Milky Way galaxy alone contains at least 17 billion Earth-sized planets, with a vast potential for life-sustaining worlds. Pursuing the exoplanet search via complementary methods are Bean and Daniel Fabrycky, another assistant professor in astronomy & astrophysics.

Bean has received a 60-orbit allocation on the Hubble Space Telescope to continue his observations on GJ 1214b, a sign of the work’s importance. Previous HST studies of planetary atmospheres encompassed 10 to 20 orbits. Bean will use a technique called transmission spectroscopy to measure the chemical composition of the planet’s atmosphere with unprecedented precision.

A big prize

A definitive assessment of the planet’s atmosphere could lead to a larger prize: learning how to detect potential signs of alien life on more Earthlike worlds. The atmospheric signature of life on an exoplanet presumably would contain some mixture of oxygen and various other gases. Planetary scientists are conducting theoretical studies to narrow the range of possibilities.

“It’s interesting to note that all the instruments astronomers have used to study exoplanet atmospheres so far were never designed for that,” Bean says. “We’re using them in very unusual ways. We do what we can with what we have.”

But now Bean aims to build a system that is optimized to study exoplanet atmospheres, including that of GJ 1214b.

“The current data suggest an atmosphere predominately composed of water, but it’s not a definitive result yet,” Bean says. “There could be even more exotic scenarios possible that we’re not able to rule out.”

If GJ 1214b is a water world, “It would be very different than anything in our own solar system,” says Harvard University astronomy Professor David Charbonneau, whose team discovered the planet.

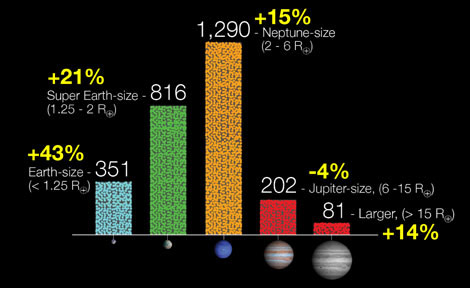

The Kepler Mission’s 2,740 planet candidates represented in this bar graph range from Earth-size at far left to larger than Jupiter at far right. Most of the planet candidates are Neptune-size. Credit: Illustration courtesy of NASA Kepler Mission

Deep questions

The search taps into some of modern science’s deepest questions: Are humans alone in the cosmos, and is our life-sustaining world unique? One of the earliest writers to speculate about exoplanets was the Italian philosopher and scientist Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake in 1600 for espousing beliefs that the Catholic Church deemed heretical.

In one prescient passage, Bruno wrote, “In space, there are countless constellations, suns, and planets; we see only the suns because they give light; the planets remain invisible, for they are small and dark. There are also numberless earths circling around their suns, no worse and no less than this globe of ours.”

Discoveries of new exoplanets have flowed like oil from a gushing wellhead in recent years. The number has topped 850 and continues to climb.

Starting in the 1990s, exoplanet hunters initially were only able to find giant, Jupiter-like gas planets because they were bigger and thus easier to find. “They were closer to their stars than Jupiter is from the sun, so we nicknamed them ‘hot Jupiters,’” Charbonneau says.

But in recent years, scientists have refined their techniques to find smaller planets like Earth. One major push along that front was the $600 million Kepler mission, launched in 2009. This mission, encompassing a 100-member science team, is conducting a survey of planets orbiting other sun-like stars.

“Kepler is on the cusp of finding small planets in the habitable zone around both sun-like and small stars,” Fabrycky says. “This is the goal of the mission, and it’s almost there.”

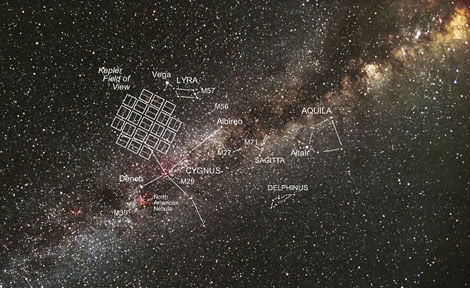

The Kepler spacecraft’s field of view is superimposed on the night sky in the image above. Launched in 2009, Kepler so far has 105 confirmed planet discoveries to its credit, and has identified 2,740 additional planet candidates. Credit: Illustration courtesy of Carter Roberts

New research frontiers at University of Chicago

A Kepler research veteran, Fabrycky began his UChicago faculty appointment last October. Fabrycky precisely measures the timing of transits, the mini eclipses that planets cause as they pass in front of their stars. Variations in the timing of transits often result from the gravitational influence of other planets. Such data allow Fabrycky to infer the structure of distant solar systems.

So far Kepler has 105 confirmed planet discoveries to its credit, and has identified 2,740 planet candidates. As a postdoctoral scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, two years ago, Fabrycky was a member of a team that discovered six planets orbiting a single star called Kepler-11. “Kepler-11 is hanging on—for the moment—as the one with the most number of planet signals” among exoplanetary systems, Fabrycky says.

Bean and his colleagues have made the best observations of planetary atmospheres so far using the Hubble Telescope, the Spitzer Space Telescope, and, in Chile, the Very Large Telescope array and the twin Magellan Telescopes. But the planned Giant Magellan Telescope, of which UChicago is a founding partner, and the forthcoming James Webb Space Telescope should eclipse the capabilities of today’s observatories when they go into service late this decade.

The new telescopes will be able to do the same sort of exoplanetary atmospheric studies underway now, “but actually do it for the smaller planets that might even be habitable,” Charbonneau says.

Please let me go visit some of those planets that may/likely hold lifeforms. I fear no “alien” lifeforms. I know I can communicate a mission of peace and coexistence in the unfathomable universes–known and unknown.

GJ1214B with just 47 light years away may hold a planet like earth with water.Similarly 107 confirmed earth like planets and suspected 2740 planets identified and yet to be confirmed are in the list by Kepler’s Mission. It is still calculated that about 17 billion earths or exoplanets are there in the Milky Way Galaxy containing about a trillion stars and a diameter of about 1,00,000 light years. However our human life is such a tiny fraction in the time scale of the universe that we exist only for about 5 minutes in a 24 hour day of this time scale of the universe compressed to a day of duration. The balance 23 hours and 55 minutes they remain as a barren land of planet chemistry which is biologically dead.The same fraction is true for any planet earth like in the galaxy. The communication in a real time for both the civilizations to exist and talk to each other is mathematically not probable. This is nothing but pure mathematics and no amount of future discovery can gainsay this truth. Even to send and receive a communication at light speed will take 94 years for such a planet which is 47 light years away. To travel physically by any mode would be still out of question. We can at the best compute number of such exoplanets by our scientific skill. Let us be happy with our updated knowledge in astronomy and any whims we can imagine in only films.Thank YOu.