DEET may chemically ‘cloak’ humans from malaria-carrying mosquitos, rather than repel them.

Since its invention during the Second World War for soldiers stationed in countries where malaria transmission rates were high, researchers have worked to pinpoint precisely how DEET actually affects mosquitos. Past studies have analyzed the chemical structure of the repellent, studied the response in easier insects to work with, such as fruit flies, and experimented with genetically engineered mosquito scent receptors grown inside frog eggs. However, the Anopheles mosquito’s neurological response to DEET and other repellents remained largely unknown because directly studying the scent-responsive neurons in the mosquito itself was technically challenging and labor-intensive work.

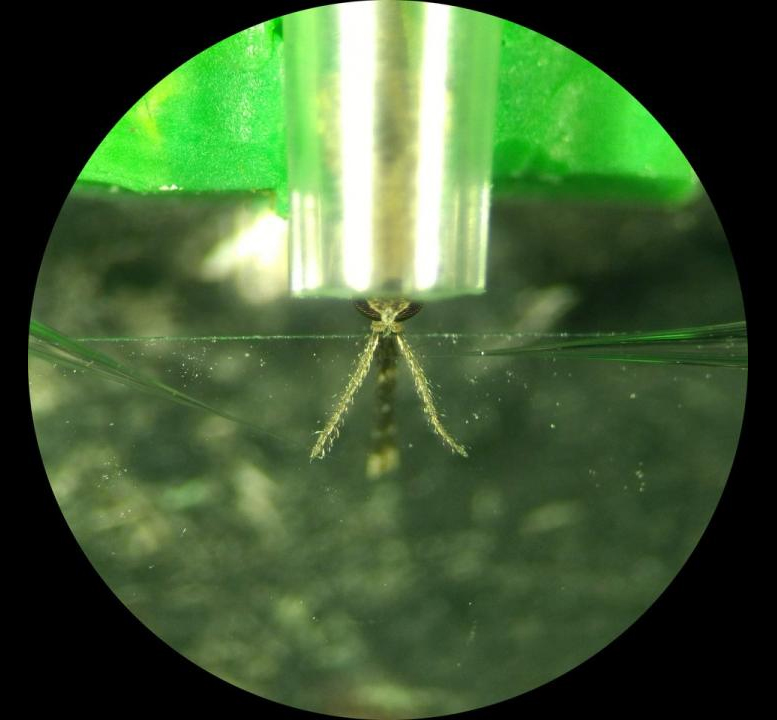

Johns Hopkins researchers have now applied a genetic engineering technique to the malaria-transmitting Anopheles mosquito, allowing them to peer at the inner workings of the insect’s nose.

“Repellents are an amazing group of odors that can prevent mosquito bites, but it’s been unclear as to how they actually work. Using our new, engineered strains of Anopheles mosquitoes, we can finally ask the question, How do the smell neurons of a mosquito respond to repellent odors?” says Christopher Potter, Ph.D., associate professor of neuroscience in the Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“Our results from Anopheles mosquitoes took us by surprise. We found that Anopheles mosquitos ‘smell’ neurons did not directly respond to DEET or other synthetic repellents, but instead, these repellents prevented human-skin odors from being able to be detected by the mosquito. In other words, these repellents were masking, or hiding, our skin odors from Anopheles.”

The group’s research was published today (October 17, 2019) in Current Biology.

“We found that DEET interacts with and masks the chemicals on our skin rather than directly repelling mosquitoes. This will help us develop new repellents that work the same way,” says Ali Afify, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the first author of this paper.

When researchers then puffed a scent that the mosquitoes could detect, such as the chemicals that make up the scent of human skin, onto the insects’ antennae, fluorescent molecules engineered by the group to be expressed in the antenna would light the neurons up and be recorded by a camera, showing that the mosquito’s nose detected the signal.

Using this odor-detecting setup, the researchers found that different scents, including chemical bug repellents such as DEET, natural repellents such as lemongrass, and chemicals found in human scent had different effects on the neurons.

When the researchers puffed the scent of DEET alone onto the mosquitoes’ antennae, the fluorescent molecules in the mosquitoes’ neurons did not light up, a sign that the mosquitoes could not directly “smell” the chemical. When exposed to the chemicals known to make up human scent, the neurons “lit up like a Christmas tree,” says Potter. And notably, when the human scent was mixed with DEET, simulating the effect of applying the repellant to the skin, the neuronal response to the mixture was tempered, resulting in a much lower response. About 20 percent of the power of the response to human scent alone.

Looking to gain insight into why this happened, the researchers measured the number of scent molecules in the air reaching the antenna to find out how much ‘smell’ was present for the insects to respond. They found that when combined with DEET, the number of human scent molecules in the air decreased to 15 percent of their previous amounts. “We, therefore, think that DEET traps human scents and prevents them from reaching the mosquitoes,” says Afify.

Potter and his team say they suspect that this effect is enough to mask the human scent and keep it from ever reaching the mosquito’s odor detectors.

The investigators caution that their study did not address the possibility that DEET and similar chemicals likely also act as contact repellents, possibly deterring Anopheles through taste or touch. The group also did not look at DEET’s effect on other species of mosquito — issues the researchers say they plan to tackle in future experiments.

“The sense of smell in insects is quite remarkable in its variety, and it is certainly possible that other types of mosquitoes such as Aedes mosquitoes, which can transmit Zika or Dengue, might actually be able to detect DEET. A key question to address would be if this detection is linked to repulsion, or if it’s perceived as just another odor by the mosquito,” says Potter.

The researchers say they also plan to study the specific chemical receptors in the brain responsible for detecting natural odors like lemongrass.

Anopheles mosquitos are the most prevalent carrier of the malaria-causing parasite Plasmodium, which spreads from person to person through infected bites. Malaria killed an estimated 435,000 people in 2017, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Reference: “Commonly Used Insect Repellents Hide Human Odors from Anopheles Mosquitoes” by Ali Afify, Joshua F. Betz, Olena Riabinina, Chloé Lahondère and Christopher J. Potter, 17 October 2019, Current Biology.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.09.007

Other researchers involved in this study include Joshua Betz of the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Olena Riabinina of Durham University, and Chloé Lahondère of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

This research was funded by the Department of Defense (W81XWH-17-PRMRP), The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI137078), a Johns Hopkins 2018 Catalyst Award, a Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute Pilot Fund and a Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.