(A) “Portrait of a Bearded Man” (Walters Art Museum #32.6), dated c. 170-180 CE from Roman Imperial Egypt; (B) The portrait under ultraviolet light. The purple clavi on the shoulders appear pink-orange, indicated by an arrow. Credit: The Walters Art Museum

Scientific analysis of an ancient portrait pigment reveals long-lost artistic details.

How much information can you get from a speck of purple pigment, no bigger than the diameter of a hair, plucked from an Egyptian portrait that’s nearly 2,000 years old? Plenty, according to a new study. Analysis of that speck can teach us about how the pigment was made, what it’s made of—and maybe even a little about the people who made it. The study is published in the International Journal of Ceramic Engineering and Science.

“We’re very interested in understanding the meaning and origin of the portraits, and finding ways to connect them and come up with a cultural understanding of why they were even painted in the first place,” says materials scientist Darryl Butt, co-author of the study and dean of the College of Mines and Earth Sciences.

Faiyum mummies

The portrait that contained the purple pigment came from an Egyptian mummy, but it doesn’t look the same as what you might initially think of as a mummy—not like the golden sarcophagus of Tutankhamen, nor like the sideways-facing paintings on murals and papyri. Not like Boris Karloff, either.

The portrait, called “Portrait of a Bearded Man,” comes from the second century when Egypt was a Roman province, hence the portraits are more lifelike and less hieroglyphic-like than Egyptian art of previous eras. Most of these portraits come from a region called Faiyum, and around 1,100 are known to exist. They’re painted on wood and were wrapped into the linens that held the mummified body. The portraits were meant to express the likeness of the person, but also their status—either actual or aspirational.

That idea of status is actually very important in this case because the man in the portrait we’re focusing on is wearing purple marks called clavi on his toga. “Since the purple pigment occurred in the clavi—the purple mark on the toga that in Ancient Rome indicated senatorial or equestrian rank- it was thought that perhaps we were seeing an augmentation of the sitter’s importance in the afterlife,” says Glenn Gates of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, where the portrait resides.

The color purple, Butt says, is viewed as a symbol of death in some cultures and a symbol of life in others. It was associated with royalty in ancient times, and still is today. Paraphrasing the author Victoria Finlay, Butt says that purple, located at the end of the visible color spectrum, can suggest the end of the known and the beginning of the unknown.

“So the presence of purple on this particular portrait made us wonder what it was made of and what it meant,” Butt says. “The color purple stimulates many questions.”

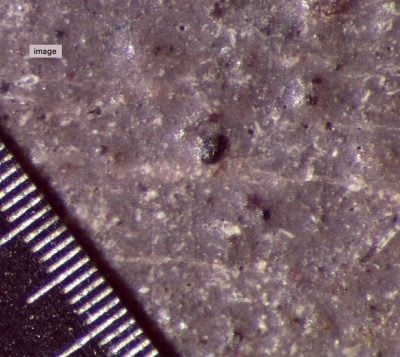

A magnified detail of the left clavus, showing a large purple pigment particle with a rough gem-like appearance. Credit: University of Utah

Lake pigments

Through a microscope, Gates saw that the pigment looked like crushed gems, containing particles ten to a hundred times larger than typical paint particles. To answer the question of how it was made, Gates sent a particle of the pigment to Butt and his team for analysis. The particle was only 50 microns in diameter, about the same as a human hair, which made keeping track of it challenging.

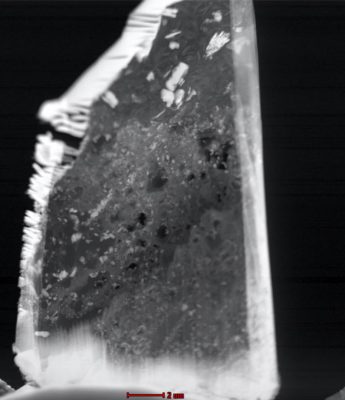

“The particle was shipped to me from Baltimore, sandwiched between two glass slides,” Butt says, “and because it had moved approximately a millimeter during transit, it took us two days to find it.” In order to move the particle to a specimen holder, the team used an eyelash with a tiny quantity of adhesive at its tip to make the transfer. “The process of analyzing something like this is a bit like doing surgery on a flea.”

With that particle, as small as it was, the researchers could machine even smaller samples using a focused ion beam and analyze those samples for their elemental composition.

What did they find? To put the results in context, you’ll need to know how dyes and pigments are made.

Pigments and dyes are not the same things. Dyes are pure coloring agents, and pigments are the combination of dyes, minerals, binders, and other components that make up what we might recognize as paint.

Initially, purple dyes came from a gland of a genus of sea snails called Murex. Butt and his colleagues hypothesize that the purple used in this mummy painting is something else—a synthetic purple.

The researchers also hypothesize that the synthetic purple could have originally been discovered by accident when red dye and blue indigo dye were mixed together. The final color may also be due to the introduction of chromium into the mix.

From there, the mineralogy of the pigment sample suggests that the dye was mixed with clay or a silica material to form a pigment. According to Butt, an accomplished painter himself, pigments made in this way are called lake pigments (derived from the same root word as lacquer). Further, the pigment was mixed with a beeswax binder before finally being painted on Linden wood.

The pigment showed evidence suggesting a crystal structure in the pigment. “Lake pigments were thought to be without crystallinity prior to this work,” Gates says. “We now know crystalline domains exist in lake pigments, and these can function to ‘trap’ evidence of the environment during pigment creation.”

Bottom of the barrel, er, vat

One other detail added a bit more depth to the story of how this portrait was made. The researchers found significant amounts of lead in the pigment as well and connected that finding with observations from a late 1800s British explorer who reported that the vats of dye in Egyptian dyers’ workshops were made of lead.

“Over time, a story or hypothesis emerged,” Butt says, “suggesting that the Egyptian dyers produced red dye in these lead vats.” And when they were done dyeing at the end of the day, he says, there may have been a sludge that developed inside the vat that was a purplish color. “Or, they were very smart and they may have found a way to take their red dye, shift the color toward purple by adding a salt with transition metals and a mordant [a substance that fixes a dye] to intentionally synthesize a purple pigment. We don’t know.”

Broader impacts

This isn’t Butt’s first time using scientific methods to learn about ancient artwork. He’s been involved with previous similar investigations and has drawn on both his research and artistic backgrounds to develop a class called “The Science of Art” that included studies and discussions on topics that involved dating, understanding, and reverse engineering a variety of historical artifacts ranging from pioneer newspapers to ancient art.

“Mixing science and art together is just fun,” he says. “It’s a great way to make learning science more accessible.”

And the work has broader impacts as well. Relatively little is known about the mummy portraits, including whether the same artist painted multiple portraits. Analyzing pigments on an atomic level might provide the chemical fingerprint needed to link portraits to each other.

“Our results suggest one tool for documenting similarities regarding time and place of production of mummy portraits since most were grave-robbed and lack archaeological context,” Gates says.

“So we might be able to connect families,” Butt adds. “We might be able to connect artists to one another.”

Reference: “Microstructural and chemical characterization of a purple pigment from a Faiyum mummy portrait” by Glenn Gates, Yaqiao Wu, Jatuporn Burns, Jennifer Watkins and Darryl P. Butt, 28 October 2020, International Journal of Ceramic Engineering and Science.

DOI: 10.1002/ces2.10075

Well I thought about it.would you want people to dig up your remains in the future, our your family. Dead bodys should not be mest with,imagine digging up old diseases, craaazy.Gewizz.leave the dead bodys, alone, you disrespect,and meddle,whoever’s disrupts the dead brings. down troubles on themselves.

You can barely spell, no one cares what you think.

Poor spelling or not, I kinda have to agree that it is disrespectful to the dead to disturb their grades and poke their corpses to satisfy curiosity. What they learn from them had no bearing on how we live in our current time and is a waste of effort. Put these “scientists” through school to work on cures for cancer.

Totally agree with C Green, all human remains should be laid to rest. As they are not objects they are humans. Click pictures and display only pictures put them back to rest.

They are scientists, not “scientists” – and science and technology is mutually reinforcing. Those scanners *are* from medical technology developments, conversely study of mummies reveal medical insights [c.f. “2000-year-old pathogen genomes reconstructed from metagenomic analysis of Egyptian mummified individuals”, BMC Biology: “Analyses of the microbiome of ancient human samples may provide insights into human health and disease, as well as pathogen evolution…”].

One *may* at this point suggest: “Put these science site “readers” through school to learn about science.”

That was auto correct, I know Hive to spell graves….

That was auto correct, I know give to spell graves….

Nah,I love digging up mummies. Finding the origins of our race

That is grave robbery in a sense but science does reveal. I never met a purple pigment human, 2,000 years ago, who knows.

I think Nanan is right. Let the dead be dead and left alone. If it has been a few thousand years then it’s up for discussion. There is little to no value in some five hundred year old grave?

There is value: c.f. “2000-year-old pathogen genomes reconstructed from metagenomic analysis of Egyptian mummified individuals”, BMC Biology: “Analyses of the microbiome of ancient human samples may provide insights into human health and disease, as well as pathogen evolution…”.

This painting looks like a relative of Colin Kapernick 🤔

I literally came here just to say that…

I find it tremendous to be able to dig up mummies and learn from their culture! When the two men found king Tuts grave it was marvelous, and what did he see? I see beautiful things , many beautiful things, he said. We knew nothing about them from those days , how did they live ? What did they eat ? How did they die ? What diseases were around then that we have erratically cured in modern times and the vaccine’s that we have now that could’ve cured them ? The art on the tombs and the writing’s , the scientists had to learn their language by figuring out the writing on the walls that explained their exhistance. It’s fascinating!!!

It’s history that we in modern times can learn from them !!! It’s history! The jewelry that they wore and the clothes that they covered themselves with ! I don’t recall people saying let the dead alone when they found the shroud of Turin ! With Jesus image on the linen cloth ! I don’t think they know if it’s real or not , they are still trying to figure it out . King Tuts tomb is very small for a king he was only 19 when he died . BUT there is another tomb behind King Tuts wall and they believe it’s his mother’s tomb , I can hardly wait !

Can’t you ?

What scientist and media need to do is stop “brightening” the pigment of the images skin to make them appear Caucasoid instead of African….and what else do we need to “learn” from Egypt that they must continue to disrespect ancient graves or risk unleashing wrath!! No boundaries, grave robbing.

What scientist and media need to do is stop “brightening” the pigment of the images skin to make them appear Caucasoid instead of African and presenting this image to the world (purple skin is black or as we say ‘blurple’ skin, i.e. the Congo)….and what else do we need to “learn” from Egypt that they must continue to disrespect ancient graves or risk unleashing wrath!! No boundaries, grave robbing.

Boo, you’re incredibly ignorant. I’m not going to go into why,I’d be here writing all day if I did. However, it’s quite evident that you hold zero degrees in any area of the sciences. As a matter of fact, judging by your own post–I doubt you even finished grade school. Smh×2. How ignorant. Making it a race issue when it just ISN’T. Go crawl back from where you came and stay there. Fun fact: Most of northern Africa ISN’T black.

Hahaha… Self-awareness not for all. I GUESS:

As a matter of fact, judging by your own post–I doubt you even finished grade school. Smh×2. How ignorant. Making it a race issue when it just ISN’T.

??? YOU GOOD

Now that the great smart mouth is leaving the auditorium, can you all stop scratching at each other. Nanan, there is a saying that goes, ‘good writers are poor spellers’, so keep at it. What does any of this have to do with grave robbery, anyway?

Nothing – Egypt wants it for science, tourism et cetera.

How many on these comments actually read the article? They were analyzing a paint chip for the person who said they’d never seen a purple person, not the person’s skin. Also, the painting was wrapped in the same bandaging as the mummy, I’m presuming that the mummy was wrapped first then the painting then together. So this meant the painting was laid on top of the body. Then I see the skin color brought into the issue. The article points out that Egypt was a Roman Province at the time in which this person died. He is most likely from a Roman, not Egyptian. Another thing, how do we, as modern humans, know what color Africans skin was even 2000 years ago. Science tells us why their skin color is darker than someone living in Europe at the same time. I’m from German, Irish, Scottish and Welsh descent. For example: I’m light complected with freckles. But if I stay out in the sun during the summer all day, I turn darker. I get more freckles and my hair bleaches out. Does that mean because I’m dark with blonde hair from being in the sun, my descent line changes. Only to those whose perceived it without knowing the facts. Stop bringing race into everything. Science tells us why we are the way we are. And without scientist being so inquisitive, not many of us would be here today since a lot of family lines would have perished from diseases of the past.

Can someone explain to me how mixing natural dye colours, and a mordant or metal salt, now makes the resulting purple “synthetic”? The terminology use is not clear. Natural dyers mix colours all the time, use morddants and modifiers and do not consider the results to be “synthetic”.

Scientists do not consider “natural” dyes natural, since most are synthesized by humans as opposed to organism colors.

And it color makes are using arguable terminology anyway, since there is no principle difference among synthetic dyes or pigments. It’s just labeling “what I personally like (versus dislike)”.

Lacquer and lake do NOT come from the same word!!!

Lake comes from Proto-Indo-European *lakw-, Proto-Indo-European *lokus, and later Proto-Indo-European *lókus (Pond, pool.).

https://etymologeek.com/dlm/lac

Lacquer comes from Sanskrit लक्ष, Sanskrit लाक्षा, Sanskrit लक्षं, and later Hindi लाख (One hundred thousand, lakh, lac.). A kind of red dye, lac (obtained from the cochineal or a similar insect as well as from the resin of a particular tree). The insect or animal which produces the red dye.

https://etymologeek.com/eng/lacquer

It’s a different “lake” than lake, obviously. Wikipedia may have the correct etymology:

“The term “lake” is derived from the term lac, the secretions of the Indian wood insect Laccifer lacca (formerly known as the Coccus lacca).[3][4] It has the same root as the word lacquer, and comes originally from the Hindi word lakh, through the Arabic word lakk and the Persian word lak.” [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_pigment ]

Other examples would be (baseball) bat and (animal) bat, et cetera.

The problem is that the apparent universal common ancestor of languages are about as old as the Indo-European cultures, so the language coalescent becomes a mess at about the same time as the gene flows do. C.f. how the common ancestor of dogs recently suddenly became much older.

What an unfortunate last name

Haha, my thoughts exactly!

He’s black and they make him look like a pale Arab .

It’s possible to learn, they get respected by modern thinking learning’s.so dig they were smart to make what they did eternal life.