Æthelstan biographer says England’s first king deserves to be remembered as anniversaries near.

A new biography of Æthelstan, recently published to mark the 1,100th anniversary of his coronation in 925AD, reaffirms his claim as the first king of England and sheds light on why his achievements remain underappreciated. The book’s author, Professor David Woodman, argues that Æthelstan’s unification of England in 927AD deserves far greater recognition.

While events such as the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and the signing of Magna Carta in 1215 are household knowledge, the pivotal years of 925 and 927AD are far less remembered. Woodman, a University of Cambridge historian and author of The First King of England, is determined to change this. Together with other scholars, he is advocating for a lasting memorial to a ruler he considers unjustly forgotten.

“As we approach the anniversaries of Æthelstan’s coronation in 925 and the birth of England itself in 927, I would like his name to become much better known. He really deserves that,” says Woodman, a Professor at Robinson College and Cambridge’s Faculty of History.

Woodman is collaborating with fellow historians to plan a memorial, which could take the form of a statue, plaque, or portrait in a significant location such as Westminster, Eamont Bridge (where Æthelstan’s authority was acknowledged by other rulers in 927), or Malmesbury (his burial place). He is also pressing for Æthelstan’s reign to be more prominently included in school curricula.

“There has been so much focus on 1066, the moment when England was conquered. It’s about time we thought about its formation, and the person who brought it together in the first place,” Professor Woodman says.

Why his legacy faded

Why is Æthelstan not more widely remembered? According to Woodman’s new book, released by Princeton University Press, the answer lies in the absence of effective publicity. “Æthelstan didn’t have a biographer writing up his story,” Woodman explains. “His grandfather, Alfred the Great, had the Welsh cleric Asser to praise his deeds. And within a few decades of Æthelstan’s death, propaganda campaigns elevated King Edgar’s reputation for reforming the church. That completely eclipsed Æthelstan’s earlier efforts to revive learning and strengthen religious life.”

In more recent centuries, many historians have also downplayed Æthelstan’s claim to be England’s first king, pointing to the kingdom’s fragmentation after his death in 939AD. Instead, attention has often shifted toward Edgar. Woodman strongly disputes this view.

“Just because things broke down after Æthelstan’s death doesn’t mean that he didn’t create England in the first place,” Woodman says. “He was so ahead of his time in his political thinking, and his actions in bringing together the English kingdom were so hard-won, that it would have been more surprising if the kingdom had stayed together. We need to recognise that his legacy, his ways of governing and legislating, continued to shape kingship for generations afterwards.”

Woodman cites a wealth of evidence to resurrect Æthelstan’s reputation.

Military success

“Militarily, Æthelstan was supremely strong,” Woodman says. “He had to be very robust to expand the kingdom and then to defend it”.

Æthelstan had to contend with major Viking settlement in the north and the east. In 927AD, he acquired authority over the Viking stronghold at York, and, in bringing Northumbria within his dominion, became the first to rule over an area recognisable as ‘England’.

As Æthelstan expanded his kingdom, he drew Welsh and Scottish kings into his royal assemblies. Large-scale surviving original diplomas, housed in the British Library, list the very many nobles he compelled to attend. The meetings of Æthelstan’s assemblies must have been incredibly grand affairs, involving hundreds of people in total.

“These Welsh and Scottish kings must have bitterly resented being brought so far out of their territories,” Woodman says. “An incredible tenth-century Welsh poem, The Great Prophecy of Britain, calls for the English to be slaughtered. It’s difficult to date, but it may be a direct response to this expansion of Æthelstan’s power.”

Then, in 937AD, at the famous Battle of Brunanburh, Æthelstan brutally crushed a formidable Viking coalition, supported by Scots and the Strathclyde Welsh, determined to overthrow him.

“Brunanburh should be as well-known as the Battle of Hastings,” Woodman says. “Every major chronicle, in England, Wales, Ireland and Scandinavia took note of this battle, its outcome, and how many people were slaughtered. It was a critically important episode in the history of the newly-formed English kingdom”.

Numerous locations have been proposed for the battle. Woodman is confident that it happened at what is now Bromborough on the Wirral. “That location makes sense strategically and the etymology of the name fits,” he says.

Revolution of government

Æthelstan’s most powerful legacy rests in his “revolution of government”, Woodman suggests. Legal documents from Æthelstan’s reign survive in relative abundance and, Woodman argues, take us right to the heart of the type of king he was.

“King Alfred must have been a role model for his grandson,” Woodman says. “Æthelstan saw that a king should legislate and he really did. He took crime very seriously.”

Once Æthelstan had created the English kingdom, royal documents known as ‘diplomas’ (in essence a grant of land by the king to a beneficiary) were suddenly transformed. Formerly short and straightforward, they were transformed into grandiose statements of royal power.

“They’re written in a much more professional script and in amazingly learned Latin, full of literary devices like rhyme, alliteration, chiasmus,” Woodman says. “They were designed to show off, he’s trumpeting his success.”

But Woodman also argues that government became increasingly efficient during Æthelstan’s reign. “We can see him sending law codes out to different parts of the kingdom, and then reports coming back to him about what was working and what changes needed to be made.”

“There is also some of the clearest evidence we have for centralised oversight of the production of royal documents, with one royal scribe put in charge of their production. No matter where the king and the royal assembly travelled, the royal scribe went too.”

Woodman points out that Æthelstan brought England together just as parts of continental Europe were fragmenting. “Nobles across Europe were rising up and taking territory for themselves,” he says. “Æthelstan made sure that he was well placed to take advantage of the unfolding of European politics by marrying a number of his half-sisters into continental ruling houses.”

Legacy of learning and religion

Woodman argues that Æthelstan reversed a decline in learning brought by the Vikings and their destruction of churches. “Æthelstan was intellectually curious and scholars from all over Europe came to his court,” Woodman says. “He sponsored learning and was a keen supporter of the church.”

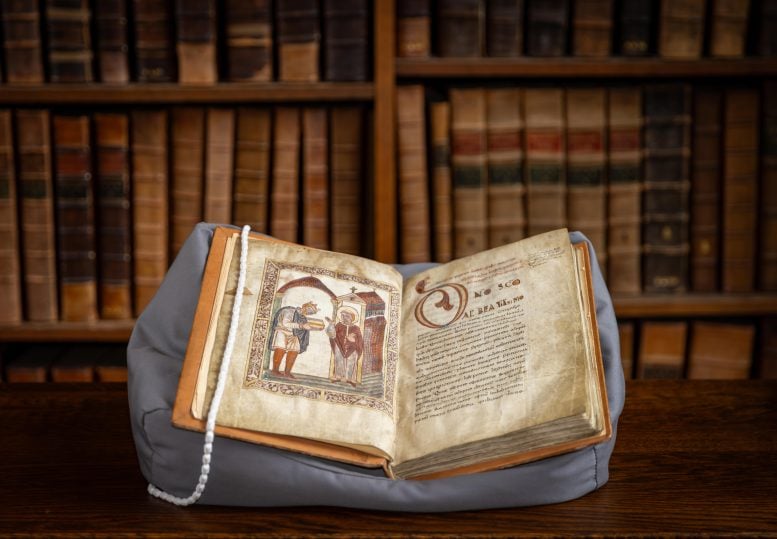

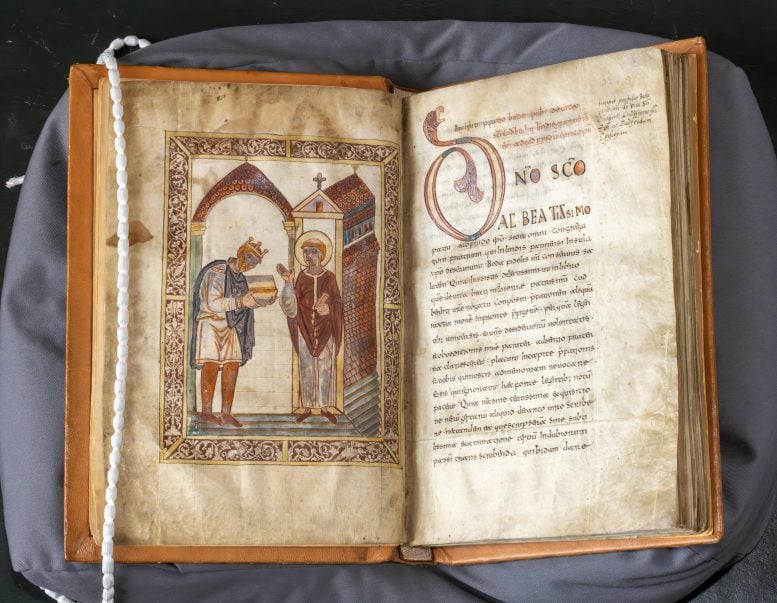

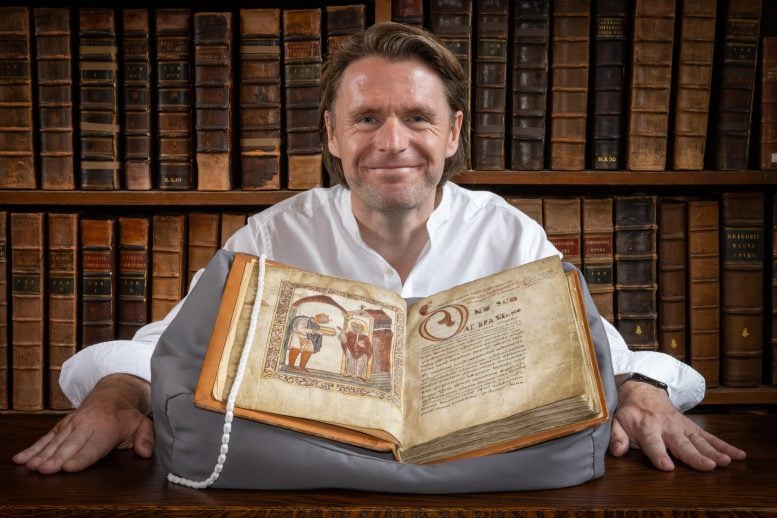

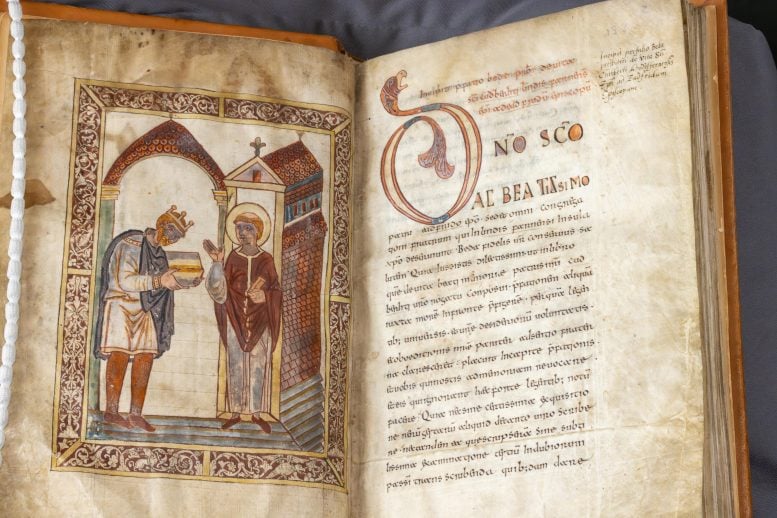

Two of Woodman’s favourite pieces of evidence relate to Saint Cuthbert. The first, the earliest surviving manuscript portrait of any English monarch, appears in a 10th-century manuscript now cared for by The Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Æthelstan’s head is bowed as he stands before the saint. “Everyone should know about this portrait, it’s one of the most important images in English history,” says Woodman.

The manuscript was originally designed as a gift for the Community of Saint Cuthbert. “Æthelstan had just expanded into Northumbria and this manuscript cleverly includes a life of Saint Cuthbert,” Woodman says. “He was trying to win them over to his cause.”

Woodman felt even closer to Æthelstan while studying the Durham Liber Vitae. Begun in the ninth century, this manuscript chronologically lists the people who had a special connection to the Community of Saint Cuthbert, in alternating gold and silver lettering.

“If Æthelstan is going to appear, he should be many pages in, but in the tenth century someone visited Saint Cuthbert’s Community and wrote ‘Æthelstan Rex’ right at the top. Seeing that was breathtakingly exciting. It’s feasible that someone in his entourage was responsible. We know they visited the Community in 934 and this manuscript may have been on prominent display there, perhaps on its high altar.”

Reference: “The First King of England: Æthelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom” by David Woodman, 2 September 2025.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

7 Comments

Well if you are going to go back to that King – why not go further into the 600’s and incorporate as much about King Arthur & what has been dug up about that era. That’s my fascination, and instead of just calling every written word a fable and imagination, how about believing what those of succeeding years could tell us about that ?

I think there going off of straight facts here

Lies.. I’ve always known/heard of this man..

The idea that England’s first king was “erased” from history is more of a popular myth than a factual claim. Athelstan was a well-documented and celebrated ruler in his own time,

I don’t think it is about lies. I learned about Athelstan in my Scottish Primary School in the 1950s and 1960s. It seems to be about which parts of history the ‘powers that be’ include in the curriculum. Historians know that William of Normandy was able to establish control in England so quickly because of the systems already in place.

I do not think that it is lies as I did not learn about Athelstan at school. The first time that I heard about him was watching Michael Wood’s excellent “In search of the Dark Ages” in the early 1980s, when I was in my mid twenties. In his episode on Athelstan, Michael acknowledged that Athelstan was largely unknown today. I have copied a link to the episode below.

https://youtu.be/0g9fVikZ8nk?si=cvAk1CzC8FLv2l6P

He was celebrate in Kingstone upon Thames on 6th Sept. with Prince Edward coming to unveil a plaque to his memory. He was crowned at the King stone which is located next to the Police Station.

Because he called Charlie Kirk a scum sucking fascist pig?