Knicole Colon, astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, seen with the James Webb Space Telesocpe at Northrop Grumman Corporation in Redondo Beach, California. Credit: Knicole Colon

With more than 4,000 planets known that orbit other stars, scientists have discovered that many of these exoplanets are quite unlike our own. NASA has a whole fleet of spacecraft that look at different aspects of these planets. Currently TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, is checking out nearby stars for possible planets. It is helping to identify candidates that future telescopes will explore further. The upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will examine the atmospheres of exoplanets and look for clues about whether they are habitable. NASA astrophysicist Knicole Colon describes her work on the Kepler, Hubble, TESS and Webb missions, and takes us on a tour of some of her favorite planets.

Jim Green: After James Webb gets launched, it’s going to find all kinds of fantastic things and enhance our understanding of habitability. But what are the real measurements that it needs to make to tell us that these planets may be habitable?

Knicole Colon: Any information we can get is really going to help us move forward in pause our understanding of the universe, really.

Jim Green: Hi, I’m Jim Green, chief scientist at NASA, and this “Gravity Assist.” On this season of “Gravity Assist” we’re looking for life beyond Earth.

Jim Green: I’m here with Dr. Knicole Colon, and she’s a research scientist, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, where she leads projects on the search for planets outside the solar system using the TESS space craft, and also planning for the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope. Welcome, Knicole, to Gravity Assist.

Knicole Colon: Thanks for having me

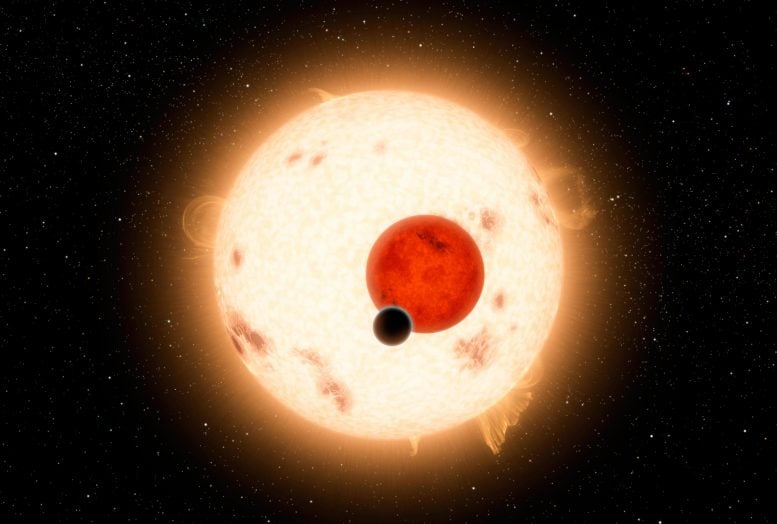

In 2011, NASA’s Kepler mission discovered a planet called Kepler-16b where two suns set over the horizon instead of just one. It is informally called a “Tatooine-like” planet because Tatooine is the name of Luke Skywalker’s home world in the science fiction movie Star Wars. But unlike in the film, Kepler-16b is not thought to be habitable. This is an illustration of Kepler-16b (shown in black) and its host stars. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt

Jim Green: Knicole, why are you so excited about exoplanets in particular?

Knicole Colon: I love exoplanets. I love thinking about exoplanets and what they could be made of, what their surfaces could be like, what kind of clouds they have, what plant life they have. I think all of that is fascinating, because we have eight planets in our solar system, plus a lot of other small bodies, and now we know of thousands of exoplanets, so that’s just a vast number, and so far they all seem really different, so that’s why I’m excited constantly to learn more and more and more about them.

Jim Green: Well, you know, I grew up in the ’60s, and we didn’t really have a good view of the Earth until Apollo 8, when we saw the Earth rise above the moon, and it completely changed my world view to where I understood this was my home, and it is a planet, and it can be compared against the others, and it really changed my perspective. So, you’ve grown up with that perspective already.

Knicole Colon: That’s right. I mean, I still was born before any exoplanets had been discovered, so I remember vaguely a time before exoplanets, but I definitely grew up knowing that it wasn’t science fiction anymore. There really were exoplanets out there and we probably are not alone.

Jim Green: Right. And one of them might look like the beautiful blue marble we call Earth.

Jim Green: Well, we’ve used a variety of telescopes, and you in particular have used ground-based in addition to the space-based telescopes, both optical and near infrared to look for planets. You know, telescopes like the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope Transit Survey Telescope has really been used by you and your group. Can you tell me more about this ground-based telescope and what are you looking for?

Knicole Colon: Sure. The KELT Transit Survey is this really fun project I became involved in about seven years ago, and the goal of the survey was to find giant planets around bright stars, to understand just how common these types of planets are. Because we don’t really have planets like these in our own solar system. These are planets that open within just a few days, so their year is a few days long, if you want to think about it like that. And with the KELT Survey, it’s actually a really cute little telescope, hence the name, we said it’s called the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope for a reason. It basically uses cameras with 42-millimeter, which is about 1.86-inch aperture, and it’s looking for transits, which is really just measuring the brightness of stars and looking for periodic dips in their brightness.

Knicole Colon: And that dip tells us that there’s a planet there around that star, and that we can see that from our point of view, all the way on Earth.

Jim Green: So, when did you start observing with this telescope, and how many planets have you found?

Knicole Colon: The KELT Survey in total has found 26 exoplanets. So, I joined the survey probably about halfway through, so it operated for about 14, 15 years.

Jim Green: Wow.

Knicole Colon: Yeah. It’s quite a long journey, but actually it just recently shut down operations, and that was partly because of the success of the TESS Satellite, the all-sky Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. So, KELT was really powerful in its heyday. But…

Jim Green: I see.

Knicole Colon: Now TESS kind of took over, but that’s okay.

Jim Green: Well, before you got involved in TESS, you were involved in another spectacular exoplanet mission, and that was the Kepler space telescope.

Jim Green: In fact, Kepler lasted far longer than what we call its nominal mission, and it made all kinds of planet observations. Thousands of planets now. So, what discovery that Kepler made got you really excited? What was the most exciting discovery in your opinion?

Knicole Colon: Yeah. For me, I think I’d have to say it was the discovery of the first circumbinary planet. So, this was called Kepler-16b, and this is a planet that orbits around two stars. And to me, it’s one thing to imagine that in science fiction, you know, in Star Wars, right?

Jim Green: That’s right. Tatooine.

Knicole Colon: But to have direct evidence from the Kepler mission of such a planetary system was so exciting. And now we’ve discovered a bunch more circumbinary planets, so it’s just all the more exciting.

Jim Green: Right. We shouldn’t be. Yeah. We should expect the unexpected when it comes to these things. Yeah, absolutely. Well, you’ve also been a member of the Hubble Space Telescope science team. What were some of your activities with that team and how did you get involved with HST?

Knicole Colon: Yeah, so a couple of years ago I ended up working… I moved from NASA Ames and working on Kepler to NASA Goddard, and again, the opportunity kind of fell in my lap to work on the Hubble team. Partly because I have an exoplanet background and the current team didn’t have anyone with that particular expertise, so I was there to really do a lot of outreach, both in terms of the public and the scientific community. And first of all, let people know that Hubble was still going strong after 30 years in space for one, so that was a big part of it, but also just making sure that the scientific community had the resources they needed to collect and analyze data from Hubble. And with a particular mindset toward exoplanet science in my role.

Jim Green: Now you’re involved in the TESS mission. Tell us more about TESS.

Knicole Colon: Yes. There are so many exciting missions right now. TESS is really… It’s building on Kepler’s legacy. So, Kepler discovered thousands of exoplanets, but TESS now, it’s been up in space since 2018, so we just had the two-year anniversary of its launch, and in that time it’s discovered also hundreds to actually over a thousand candidate planets right now as well, too. But the difference with Kepler is that it’s discovering a lot of these planets around bright nearby stars, so stars that we can follow up then with other facilities, like Hubble, and really characterize these planets in detail and study their atmospheres.

Jim Green: So, indeed, Kepler looked at planets around stars that are very far away, and with the bright stars, which is what TESS is looking for, these are typically closer to the Earth. Are there any planets that are emerging from the TESS surveys that are exciting you?

Knicole Colon: Definitely. I may be a little biased here, but I will say one of the most exciting discoveries was one that a team I am part of made, and it’s a three-planet system around a small star. But one of the planets is smaller than Earth, and it’s just incredible that we’re seeing that around these bright nearby stars, and they’re already being studied with the Hubble telescope, as well, to start to get a glimpse of what their atmosphere may be composed of.

Jim Green: Well, you know, as you say, these kind of space telescopes will see these transits, that means watch the light of the star go down and then go back up because the planet moves in front of that star, but what we’d really like to do is confirm that, and that means figure out that orbit and then watch it happen again.

Jim Green: Kepler observed so many planets, and we were able with Kepler to determine the distribution of planets. Were there any surprises that came out of that?

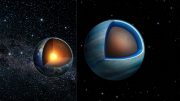

Knicole Colon: So my goal in being an exoplanet scientist has been to understand how common planets are from our own solar system. So, how common are Jupiters? How common are Earths, right? But Kepler comes along and says, “Wait a minute. The most common size planet is actually smaller than Neptune in our own solar system.” So, it’s between the size of Earth and Neptune, and we have nothing like that in our solar system. So how is it that the most common-size planet is not found in our solar system? That blows my mind, and that means we have so much more to learn.

Jim Green: Yeah. Actually, that was the big surprise for me, too. You know, approaching it as a planetary scientist, I thought, “Okay, when nebulas collapse, we’re going to get stars, but there are also going to be some big planets.” I would have thought there would be a lot of Jupiters, but that isn’t the case. These bigger planets that you call super Earths, or mini Neptunes, that are between the size of Earth and Neptune, really are these new planets that are so exciting to study.

Jim Green: Well, you mentioned this new type of planet. Is that what I would call your favorite type of planet that you’re looking for, a super-Earth?

Knicole Colon: You know, it’s one of them. I have a lot of favorites. That is certainly one, just because it is so different from our solar system, but there is kind of another emerging class that I’m pretty interested in, and these are what are called extremely low-density planets, or I like to just call them puffy planets. Where they’re so low density, imagine having the density of styrofoam, basically. And that’s what we’re talking about here.

Knicole Colon: And they’re Jupiters in size, though, so it’s kind of deceiving. You think, “Oh, they’re just giant planets.” But then they have really low masses, and I’m curious to know how did these guys form and evolve, and retain this really fluffy atmosphere, because that’s presumably what’s happening here. So, finding that out-

Jim Green: That’s right.

Knicole Colon: … is interesting.

Jim Green: Indeed. Jupiter, if it was a big fish bowl, you could put a thousand Earths in that fish bowl, and yet Jupiter, its mass is only about 300 times the mass of the Earth. So, that means its density is much less than Earth’s. So, there’s something about what’s in the core, what the composition of that is, whether there’s rocky material there or not, and so there’s a lot of physics yet in terms of planetary formation that these puffy, large planets will tell us about.

Knicole Colon: Absolutely.

NASA astrophysicists Knicole Colon and Elisa Quintana with stickers from some of NASA’s exoplanet missions. Credit: Knicole Colon

Jim Green: Well, another activity that you’re very much involved in is our new, fantastic telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope. What’s your role in that particular mission?

Knicole Colon: Yeah. I’m very excited to have this role. It basically revolves around everything exoplanets, so I engage with the community on all things exoplanets, both in terms of doing public outreach, but also really communicating with scientists about how Webb can study exoplanets, and how it’s already being planned to study exoplanets. So, we already have programs in the works to study exoplanets, so making sure they’re aware of what’s in the plan for its first year of science, for instance.

Knicole Colon: And really, I also work with the rest of the Webb team to make sure that we have all the necessary tools in place to analyze that exoplanet data once we get it, so that we can be sure to extract the scientific results and learn from them. You know, that’s the end goal.

Knicole Colon: It’s basically going to be able to access these long infrared wavelengths that we cannot currently access with space telescopes. And not only that, but it has improved sensitivity, so we can make really these measurements of really small signals. For instance, from atmospheres of exoplanets. But beyond you know, science and those types of observational capabilities, it’s really neat to think about the technological aspects of Webb. I mean, Webb has this huge, 6.5-meter (21-foot) primary mirror, and it’s actually made up of 18 separate segments that will unfold after the telescope launches and then they’ll serve as a single mirror.

Knicole Colon: So, that whole unfolding in space thing is really fascinating, and making sure it works is a whole ‘nother game. And then not to mention Webb also has a sun shield that’s literally the size of a tennis court, and that’s going to help keep Webb cool, so that it can make these really sensitive measurements. So, all these different special kind of components come together to make sure we can do some really groundbreaking science.

Jim Green: Yeah, so Webb is the largest space telescope that we’ve ever put into orbit, and it should be absolutely fantastic in terms of its ability to see different objects in that infrared range. Anything that’s in space that’s hot will generate a signal it can see, and so all our planets are still cooling off from when they were made, 4.6 billion years ago. So, I’m too really excited about what Webb can do. Not only looking within our solar system, but well looking out at a variety of exoplanets. So, what do you think the biggest contribution Webb’s going to be making in terms of looking at these exoplanets?

Knicole Colon: Webb is going to look at really a variety of planets, ranging from ones as small as Earth, that orbit stars much smaller than our own sun, to giant planets that orbit giant stars. So, I think Webb is really going to be able to give us new information beyond what Hubble has given us already. With Webb, we’re going to be able to look for concrete evidence of methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, these types of chemicals in exoplanet atmospheres, and these are really important to understand how these exoplanets form, how their atmospheres form, how did they evolve? Because all of this, again, helps us with that journey to understand our own solar system planets. So, any information we can get is really going to help us move forward in our understanding of the universe, really.

Jim Green: So, indeed, if Webb sees these exoplanets and their atmospheres, what will it be looking for in the infrared?

Knicole Colon: Yeah, so there are actually two ways that Webb looks at exoplanets, and so we already talked about the one where Webb will look at transiting exoplanets. So, Webb will see a planet pass in front of, or sometimes it looks when the planet passes behind the star, and in that case, either way, you’re measuring the dip in brightness from the system, and then you’re extracting that information as a function of wavelength of light. And so, in the infrared, you end up looking for, basically, dips in the light that is telling you, “Oh, there’s methane absorbing in the atmosphere of this planet.” And that’s something that we can see with Webb, and we can do this for all size exoplanets, from giant ones to small ones, so that’s really exciting. And Webb will be able to do that for a lot of planets.

Knicole Colon: But then on the flip side, Webb also has the ability to take direct images of planets. So, it’s basically like someone might take a picture with the camera on their phone. Of course, though, the instruments on Webb are designed differently, so that when you’re taking a picture of a star with a planet, the instrument is designed so you suppress that starlight, because it’s super bright compared to the planet, and you just want that faint little glow from the planet, and that’s what we’re trying to get at here. And from that, similarly, you can say, “Oh, is there methane, carbon dioxide, whatnot in the atmosphere?” From that little pale dot.

Knicole Colon: The difficulty, of course, is that the atmospheres of rocky planets are really, really thin, and so Webb will be able to provide… we’ll say like a first glimpse into the atmospheres of rocky small planets that might be also the right temperature to have liquid water on their surface, and might be the right conditions to have life on their surface. But I think Webb is really the first step in a journey here, where we have future telescopes being designed right now and considered, that might be built, that could really push the boundaries even further and provide us with that really definitive evidence of, “Okay, this has an atmosphere conducive to life.”

Jim Green: Well, that’s really exciting. Do you personally think there’s life beyond Earth?

Knicole Colon: You know, I do. I do think that. I have no idea what type of life there could be, if it’s anything whatsoever like what’s found on Earth, but at the same time, Earth has so many different types of life that exist in so many different environments, that I just don’t see how there can’t be life outside of Earth. Maybe we’ll discover it in my lifetime. One can hope. But-

Jim Green: No. We’ve got to be able to do that. We’re hot on the trail.

Knicole Colon: That’s right.

Jim Green: So, don’t give up. Get going and let’s do that.

Jim Green: Well, Knicole, I always like to ask my guest to tell me what was that event or person, place, or thing that happened to them that got them so excited that they became the scientist they are today. I call that event a gravity assist. So, Knicole, what was your gravity assist?

Knicole Colon: Is it okay if I give two answers?

Jim Green: Of course. Yeah, sometimes we all need a little extra.

Knicole Colon: Yeah. Well, for me, it was kind of two simultaneous events. And really, it boils down to being a young teenager, and I fell in love with science fiction at the same time that my dad started encouraging me to have an interest in astronomy, and his interest came from the fact that he was just interested in everything, so he saw I started liking science fiction, and certain movies really inspired me, and he encouraged me to pursue astronomy. And those things really had me excited about the idea of being a scientist, and now to this day, I still am excited about being a scientist, so I guess it all worked out.

Jim Green: Well, I can see now, as you say the science fiction part of it, why you were so excited to find Tatooine, a planet orbiting two stars. But I had heard that you were really excited about the book that Carl Sagan wrote, Contact, and then the subsequent movie about finding life beyond Earth.

Knicole Colon: Yes. 100%. That is one of the first books and movies that just really floored me. I mean, I was wondering what would it really be like if we found life? How would humanity react? How would we communicate with them? Could I actually do something like this myself when I grow up? And here I am, however many years later.

Jim Green: That’s right.

Knicole Colon: Working on that goal with TESS and Webb.

Jim Green: That’s right. Indeed. Actually, you’re right. We need to also start thinking ahead a little bit of what has to happen, or what will happen when we announce for sure that there is life beyond Earth, and how we’re going to explain it, how we’re going to interact with the public, what we think their interactions will be, their reactions, and try to anticipate those.

Knicole Colon: Yeah. It’s going to be really interesting. That’s why I hope I’m around when that happens, too. In my lifetime.

Jim Green: Well, just make it happen. I want you to do that. I want you to find it.

Knicole Colon: I’ll work on that.

Jim Green: All right. Well, good. Great. Well, Knicole, thanks so much. I really enjoyed talking to you today about all your vast experience and the progress that we’re making in looking for life beyond Earth with exoplanets.

Knicole Colon: Thank you so much for having me. I really enjoyed talking with you.

Jim Green: Well, join me next time as we continue our journey to look for life beyond Earth. I’m Jim Green, and this is your “Gravity Assist.”

Be the first to comment on "NASA Gravity Assist: Puffy Planets and Powerful Telescopes"