Astronomers detected a giant planet orbiting a small star. The planet has much more mass than theoretical models predict. While this surprising discovery was made by a Spanish-German team at an observatory in southern Spain, researchers at the University of Bern studied how the mysterious exoplanet might have formed.

The red dwarf GJ 3512 is located 30 light-years from us. Although the star is only about a tenth of the mass of the Sun, it possesses a giant planet – an unexpected observation. “Around such stars there should only be planets the size of the Earth or somewhat more massive Super-Earths,” says Christoph Mordasini, professor at the University of Bern and member of the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS: “GJ 3512b, however, is a giant planet with a mass about half as big as the one of Jupiter, and thus at least one order of magnitude more massive than the planets predicted by theoretical models for such small stars.”

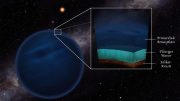

The exoplanet GJ 3512b was discovered by the CARMENES consortium with an instrument installed at the Calar Alto Observatory in southern Spain. Credit: Pedro Amado/Marco Azzaro – IAA/CSIC

The mysterious planet was detected by a Spanish-German research consortium called CARMENES, which has set itself the goal of discovering planets around the smallest stars. For this purpose, the consortium built a new instrument, which was installed at the Calar Alto Observatory at 2100 m altitude in southern Spain. Observations with this infrared spectrograph showed that the small star regularly moved towards and away from us – a phenomenon triggered by a companion who had to be particularly massive in this case. Because this discovery was so unexpected, the consortium contacted, among others, the Bern research group of Mordasini, one of the world’s leading experts in the theory of planet formation, to discuss plausible formation scenarios for the giant exoplanet. The paper with all contributions has now been published in the journal Science.

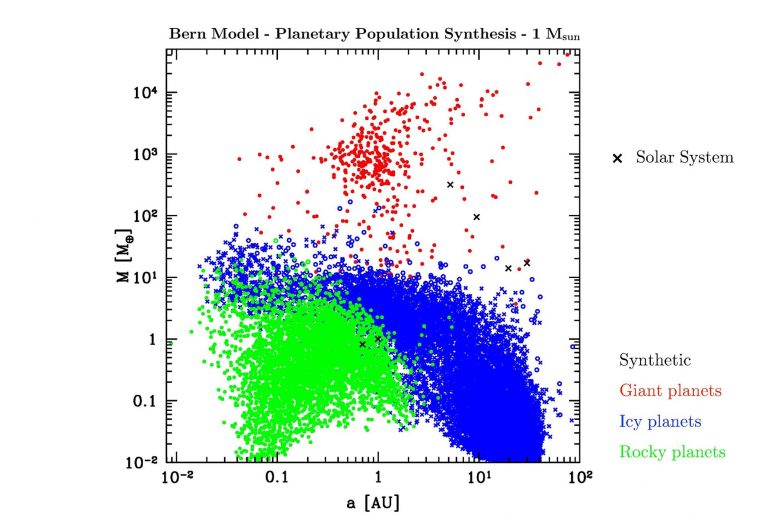

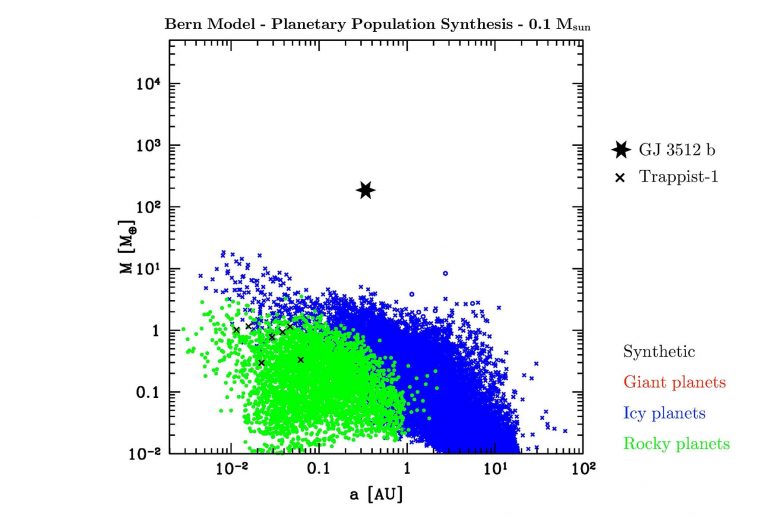

Comparison of the planetary population synthesis of the Bern Model with the solar system, and with Trappist 1 and GJ 3512b. The solar system and Trappist 1 are in accordance with the model, GJ 3512b is much more massive than the predictions of the model. Credit: University of Bern, graphics: Christoph Mordasini

Bottom-up process or collapse?

“Our model of the formation and evolution of planets predicts that around small stars a large number of small planets will be formed,” Mordasini summarizes, referring to another well-known planetary system as an example: Trappist-1. This star comparable to GJ 3512 has seven planets with masses roughly equal to or even less than the mass of the Earth. In this case, the calculations of the Bern model agree well with the observation. Not so with GJ 3512. “Our model predicts that there should be no giant planets around such stars,” says Mordasini. One possible explanation for the failure of the current theory could be the mechanism underlying the model, known as core accretion. Planets are formed by the gradual growth of small bodies into ever-larger masses. The experts call this a “bottom-up process.”

Maybe the giant planet GJ 3512b was formed by a fundamentally different mechanism, a so-called gravitational collapse. “A part of the gas disk in which the planets are formed collapses directly under its own gravitational force,” explains Mordasini: “A top-down process.” But even this explanation poses problems. “Why hasn’t the planet continued to grow and migrate closer to the star in this case? You would expect both if the gas disk had enough mass to become unstable under its gravity,” says the expert and adds: “The planet GJ 3512b is therefore an important discovery that should improve our understanding of how planets form around such stars.”

Christoph Mordasini Physics Institute, University of Bern. Credit: University of Bern

Reference: “A giant exoplanet orbiting a very-low-mass star challenges planet formation models” by J. C. Morales, A. J. Mustill, I. Ribas, M. B. Davies, A. Reiners, F. F. Bauer, D. Kossakowski, E. Herrero, E. Rodríguez, M. J. López-González, C. Rodríguez-López, V. J. S. Béjar, L. González-Cuesta, R. Luque, E. Pallé, M. Perger, D. Baroch, A. Johansen, H. Klahr, C. Mordasini, G. Anglada-Escudé, J. A. Caballero, M. Cortés-Contreras, S. Dreizler, M. Lafarga, E. Nagel, V. M. Passegger, S. Reffert, A. Rosich, A. Schweitzer, L. Tal-Or, T. Trifonov, M. Zechmeister, A. Quirrenbach, P. J. Amado, E. W. Guenther, H.-J. Hagen, T. Henning, S. V. Jeffers, A. Kaminski, M. Kürster, D. Montes, W. Seifert, F. J. Abellán, M. Abril, J. Aceituno, F. J. Aceituno, F. J. Alonso-Floriano, M. Ammler-von Eiff, R. Antona, B. Arroyo-Torres, M. Azzaro, D. Barrado, S. Becerril-Jarque, D. Benítez, Z. M. Berdiñas, G. Bergond, M. Brinkmöller, C. del Burgo, R. Burn, R. Calvo-Ortega, J. Cano, M. C. Cárdenas, C. Cardona Guillén, J. Carro, E. Casal, V. Casanova, N. Casasayas-Barris, P. Chaturvedi, C. Cifuentes, A. Claret, J. Colomé, S. Czesla, E. Díez-Alonso, R. Dorda, A. Emsenhuber, M. Fernández, A. Fernández-Martín, I. M. Ferro, B. Fuhrmeister, D. Galadí-Enríquez, I. Gallardo Cava, M. L. García Vargas, A. Garcia-Piquer, L. Gesa, E. González-Álvarez, J. I. González Hernández, R. González-Peinado, J. Guàrdia, A. Guijarro, E. de Guindos, A. P. Hatzes, P. H. Hauschildt, R. P. Hedrosa, I. Hermelo, R. Hernández Arabi, F. Hernández Otero, D. Hintz, G. Holgado, A. Huber, P. Huke, E. N. Johnson, E. de Juan, M. Kehr, J. Kemmer, M. Kim, J. Klüter, A. Klutsch, F. Labarga, N. Labiche, S. Lalitha, M. Lampón, L. M. Lara, R. Launhardt, F. J. Lázaro, J.-L. Lizon, M. Llamas, N. Lodieu, M. López del Fresno, J. F. López Salas, J. López-Santiago, H. Magán Madinabeitia, U. Mall, L. Mancini, H. Mandel, E. Marfil, J. A. Marín Molina, E. L. Martín, P. Martín-Fernández, S. Martín-Ruiz, H. Martínez-Rodríguez, C. J. Marvin, E. Mirabet, A. Moya, V. Naranjo, R. P. Nelson, L. Nortmann, G. Nowak, A. Ofir, J. Pascual, A. Pavlov, S. Pedraz, D. Pérez Medialdea, A. Pérez-Calpena, M. A. C. Perryman, O. Rabaza, A. Ramón Ballesta, R. Rebolo, P. Redondo, H.-W. Rix, F. Rodler, A. Rodríguez Trinidad, S. Sabotta, S. Sadegi, M. Salz, E. Sánchez-Blanco, M. A. Sánchez Carrasco, A. Sánchez-López, J. Sanz-Forcada, P. Sarkis, L. F. Sarmiento, S. Schäfer, M. Schlecker, J. H. M. M. Schmitt, P. Schöfer, E. Solano, A. Sota, O. Stahl, S. Stock, T. Stuber, J. Stürmer, J. C. Suárez, H. M. Tabernero, S. M. Tulloch, G. Veredas, J. I. Vico-Linares, F. Vilardell, K. Wagner, J. Winkler, V. Wolthoff, F. Yan and M. R. Zapatero Osorio, 27 September 2019, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.aax3198

Read more about this unusual planet:

I am amazed to see people do so much research about our worlds!

My life has made to 66. Just another veteran with 8 tours of duty in the Bosnian crisis.

All I saw in the sky was fire rockets and smoke! the earth around me was destroyed! I look in the sky today, and still see fire and mayhem down below. 8500 years of human conflict on earth.

Do you think you will find peace out there? Hope so. keep up the good work!

The researchers seem fundamentally predisposed to conclude that the planet formed as a natural satellite of the planet it now orbits. This seems like a baseless conclusion, to me.

If you want to see evidence of rogue planets wandering the galaxy, look at OGLE-2016-BLG-1928.

If you want to see evidence supporting the notion that rogue satellites can become gravitationally bound to another body, look up at night. You might see the rocky body of a moon up there that may not have formed naturally in our orbit.

Two plus two does not equal eight, but investigating whether or not this star would have been fundamentally capable of supporting the development of such a planet either through ordinary processes or the gravitational collapse of a gas disk is a valid process. It just seems that the possibility of the planet forming elsewhere and then becoming fixed in an orbit around this star represents an equal or greater probability.