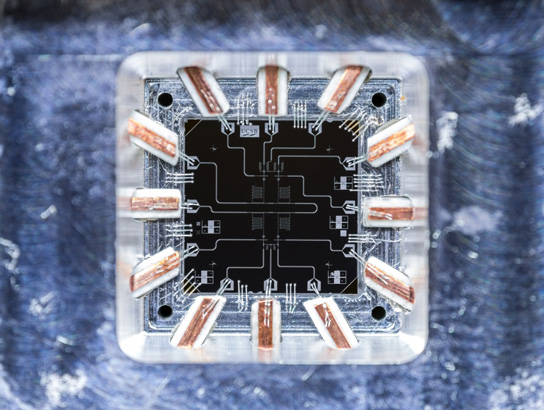

UCSB physicists worked on a new qubit architecture, which is an essential ingredient for quantum simulation, and allowed them to master the seven parameters necessary for complete control of a two-qubit system. Credit: Michael Fang, Martinis Lab

In a newly published study, UCSB physicists demonstrate the high level of controllability needed to explore ideas in quantum simulations.

While the Martinis Lab at UC Santa Barbara has been focusing on quantum computation, former postdoctoral fellow Pedram Roushan and several colleagues have been exploring qubits (quantum bits) for quantum simulation on a smaller scale. Their research appears in the current edition of the journal Nature.

“While we’re waiting on quantum computers, there are specific problems from various fields ranging from chemistry to condensed matter that we can address systematically with superconducting qubits,” said Roushan, who is now a quantum electronics engineer at Google. “These quantum simulation problems usually demand more control over the qubit system.” Earlier this year, John M. Martinis and several members of his UCSB lab joined Google, which established a satellite office at UCSB.

In conjunction with developing a general-purpose quantum computer, Martinis’ team worked on a new qubit architecture, which is an essential ingredient for quantum simulation, and allowed them to master the seven parameters necessary for complete control of a two-qubit system. Unlike a classical computer bit with only two possible states — 0 and 1 — a qubit can be in either state or a superposition of both at the same time, creating many possibilities of interaction.

One of the crucial specifications — Roushan refers to them as control knobs or switches — is the connectivity, which determines whether or not, and how, the two qubits interact. Think of the two qubits as people involved in a conversation. The researchers have been able to control every aspect — location, content, volume, tone, accent, etc. — of the communication. In quantum simulation, full control of the system is a holy grail and becomes more difficult to achieve as the size of the system grows.

“There are lots of technological challenges, and hence learnings involved in this project,” Roushan said. “The icing on the cake is a demonstration that we chose from topology.” Topology, the mathematical study of shapes and spaces, served as a good demonstration of the power of full control of a two-qubit system.

In this work, the team demonstrates a quantum version of Gauss’s law. First came the 19th-century Gauss-Bonnet theorem, which relates the total local curvature of the surface of a geometrical object, such as a sphere or a doughnut, to the number of holes in the object (zero for the sphere and one for the doughnut). “Gauss’s law in electromagnetism essentially provides the same relation: Measuring curvature on the surface — in this case, an electric field — tells you something about what is inside the surface: the charge,” Roushan explained.

The novelty of the experiment is how the curvature was measured. Project collaborators at Boston University suggested an ingenious method: sensing the curvature through movement. How local curvature affects the motion can be understood from another analogy with electromagnetism: the Lorentz force law, which says that a charged particle in a magnetic field, which curves the space, is deflected from the straight pass. In their quantum system, the researchers measured the amount of deflection along one meridian of a sphere’s curve and deduced the local curvature from that.

“When you think about it, it is pretty amazing,” Roushan said. “You do not need to go inside to see what is in there. Moving on the surface tells you all you need to know about what is inside a surface.”

This kind of simulation — arbitrary control over all parameters in a closed system — contributes to a body of knowledge that is growing, and the paper describing that demonstration is a key step in that direction. “The technology for quantum computing is in its infancy in a sense that it’s not fully clear what platform and what architecture we need to develop,” Roushan said. “It’s like a computer 50 years ago. We need to figure out what material to use for RAM and for the CPU. It’s not obvious so we try different architectures and layouts. One could argue that what we’ve shown is very crucial for coupling qubits when you’re asking for a full-fledged quantum computer.”

Reference: “Observation of topological transitions in interacting quantum circuits” by P. Roushan, C. Neill, Yu Chen, M. Kolodrubetz, C. Quintana, N. Leung, M. Fang, R. Barends, B. Campbell, Z. Chen, B. Chiaro, A. Dunsworth, E. Jeffrey, J. Kelly, A. Megrant, J. Mutus, P. J. J. O’Malley, D. Sank, A. Vainsencher, J. Wenner, T. White, A. Polkovnikov, A. N. Cleland and J. M. Martinis, 12 November 2014, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/nature13891

Lead co-authors are UCSB’s Charles Neill and Yu Chen, of Google Inc., Santa Barbara. Other UCSB co-authors include Rami Barends, Brooks Campbell, Zijun Chen, Ben Chiaro, Andrew N. Cleland, Andrew Dunsworth, Michael Fang, Julian Kelly, Nelson Leung, Anthony Megrant, Josh Mutus, Peter O’Malley, Chris Quintana, Amit Vainsencher, Jim Wenner and Ted White, as well as Evan Jeffrey, Martinis and Daniel Sank of Google Inc., Santa Barbara, and Michael Kolodrubetz and Anatoli Polkovnikov of Boston University.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity. Devices were made at the UCSB Nanofabrication Facility, part of the NSF-funded National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network and the NanoStructures Cleanroom Facility.

Be the first to comment on "Physicists Demonstrate Control of a Two-Qubit System"