A record-shattering lightning bolt traveled an astonishing 515 miles from Texas to near Kansas City, becoming the longest ever recorded.

This megaflash was only uncovered years later by satellites in orbit equipped with advanced lightning mappers, revealing the scale and mystery of these rare electrical phenomena.

Record-Shattering Lightning Flash

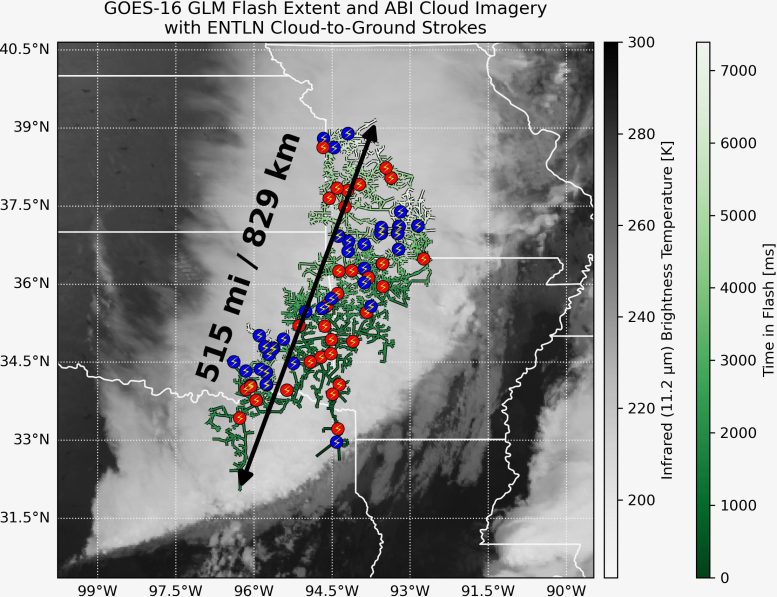

A single lightning bolt stretched an incredible 515 miles across the Great Plains, beginning in eastern Texas and reaching nearly to Kansas City. This massive flash has now been confirmed as the longest lightning event ever recorded.

“We call it megaflash lightning and we’re just now figuring out the mechanics of how and why it occurs,” said Randy Cerveny, an Arizona State University President’s Professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning.

Cerveny and his team identified the record-breaking megaflash using satellite-based tools that captured the event during a powerful thunderstorm in October 2017. The bolt’s extraordinary length exceeded the previous record of 477 miles, set in April 2020 during a storm in the southern United States, by a full 38 miles. The 2017 flash had gone unnoticed until researchers reviewed archived satellite data years later.

Expect More Lightning Extremes Ahead

“It is likely that even greater extremes still exist, and that we will be able to observe them as additional high-quality lightning measurements accumulate over time,” said Cerveny, who serves as rapporteur of weather and climate extremes for the World Meteorological Organization, the weather agency of the United Nations.

Before satellite technology, scientists relied on ground-based antenna networks to detect lightning. These systems worked by picking up radio signals from lightning strikes and calculating their path using the time it took signals to reach different locations.

That changed in 2017, when satellites equipped with advanced lightning detectors began providing continuous, large-scale coverage from space. These instruments made it possible to track lightning flashes across entire continents with precise timing and detail.

“Our weather satellites carry very exacting lightning detection equipment that we can use document to the millisecond when a lightning flash starts and how far it travels,” Cerveny said.

Global Lightning Coverage Expands

Parked in geostationary orbit, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency’s GOES-16 satellite detects around one million lightning flashes per day. It is the first of four NOAA satellites equipped with geostationary lightning mappers, joined by similar satellites launched by Europe and China.

“Adding continuous measurements from geostationary orbit was a major advance,” said Michael Peterson at the Georgia Tech Research Institute. “We are now at a point where most of the global megaflash hotspots are covered by a geostationary satellite, and data processing techniques have improved to properly represent flashes in the vast quantity of observational data at all scales.” Peterson is first author of a report in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society documenting the new lightning record.

What Makes a Flash ‘Mega’?

Most lightning flashes are limited to less than 10 miles in reach. When a lightning bolt reaches beyond 60 miles (100 kilometers to be exact), it’s considered a megaflash. Less than 1 percent of thunderstorms produce megaflash lightning, according to satellite observations analyzed by Peterson. They arise from storms that are long-lived, typically brewing for 14 hours or more, and massive in size, covering an area comparable in square miles to the state of New Jersey. The average megaflash shoots off five to seven ground-striking branches from its horizontal path across the sky.

While megaflashes that extend hundreds of miles are rare, it’s not at all unusual for lightning to strike 10 or 15 miles from its storm-cloud origin, Cerveny said. And that adds to the danger. Cerveny said people don’t realize how far lightning can reach from its parent thunderstorm.

Lightning Danger Often Comes After the Storm

Lightning kills 20 to 30 people each year in the U.S. and injures hundreds more. Most lightning strike injuries occur before and after the thunderstorm has peaked, not at the height of the storm.

“That’s why you should wait at least a half an hour after a thunderstorm passes before you go out and resume normal activities,” Cerveny said. “The storm that produces a lightning strike doesn’t have to be over the top of you.”

Reference: “A New WMO-Certified Single Megaflash Lightning Record Distance: 829 km (515 mi) occurring on 22 October 2017” by Michael J. Peterson, Rachel Albrecht, Sven-Erik Enno, Ronald L. Holle, Timothy Lang, Timothy Logan, Walter A. Lyons, Joan Montanya, Shriram Sharma, Yoav Yair, Jessica Losego and Randall S. Cerveny, 31 July 2025, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

DOI: 10.1175/BAMS-D-25-0037.1

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

2 Comments

When my son played baseball, league officials would only stop the game if lightning was seen. These facts about lightning need to be circulated nationally, especially to the administrations of outdoor sport leagues to keep players safe, especially kids.

what state / latitude is that?