New research has found that children with autism experience significant memory challenges, impacting their ability to recall faces and other information. These memory impairments, observed through distinct brain wiring patterns, extend beyond just social memory, suggesting that autism therapies need a broader approach.

Stanford Medicine researchers have demonstrated that memory challenges in autism are not limited to facial recognition. This discovery indicates a broader involvement of memory in the neurobiology of the condition.

Children with autism face memory challenges that impact not only their recall of faces but also their ability to remember various types of information, a study from the Stanford School of Medicine reveals. These impairments are reflected in distinct wiring patterns in the children’s brains, the study found.

The study, published in the journal Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, sheds light on the ongoing discussion concerning memory capabilities in children with autism. It demonstrates that their memory challenges extend beyond forming social memories. The finding should prompt broader thinking about autism in children and about the treatment of the developmental disorder, according to the scientists who conducted the study.

“Many high-functioning kids with autism go to mainstream schools and receive the same instruction as other kids,” said lead author Jin Liu, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in psychiatry and behavioral sciences. Memory is a key predictor of academic success, said Liu, adding that memory challenges may put kids with autism at a disadvantage.

The study’s findings also raise a philosophical debate about the neural origins of autism, the researchers said. Social challenges are recognized as a core feature of autism, but it’s possible that memory impairments significantly contribute to the ability to engage socially.

“Social cognition cannot occur without reliable memory,” said senior author Vinod Menon, PhD, the Rachael L. and Walter F. Nichols, MD, Professor and a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

“Social behaviors are complex, and they involve multiple brain processes, including associating faces and voices to particular contexts, which require robust episodic memory,” Menon said. “Impairments in forming these associative memory traces could form one of the foundational elements in autism.”

Comprehensive memory tests

Autism, which affects about one in every 36 children, is characterized by social impairments and restricted repetitive behaviors. The condition exists on a wide spectrum. The most severely affected individuals cannot speak or care for themselves, and about one-third of people with autism have intellectual impairments. On the other end of the spectrum, many people with high-functioning autism have a normal or high IQ, complete higher education, and work in a variety of fields.

Research has shown that children with autism have difficulty remembering faces. Some research has also suggested that children with autism have broader memory difficulties, but these studies were small and did not thoroughly assess participants’ memory abilities. They included children with wide ranges of age and IQ, both of which influence memory.

To clarify the impact of autism on memory, the new study included 25 children with high-functioning autism and normal IQs who were 8 to 12 years old, and a control group of 29 typically developing children with similar ages and IQs.

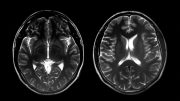

All participants completed a comprehensive evaluation of their memory skills, including their ability to remember faces; written material; and non-social photographs, or photos without any people. The scientists tested participants’ ability to accurately recognize information (identifying whether they had seen an image or heard a word before) and recall it (describing or reproducing details of information they had seen or heard before). The researchers tested participants’ memory after delays of varying lengths. All participants also received functional magnetic resonance imaging scans of their brains to evaluate how regions known to be involved in memory are connected to each other.

Distinct brain networks drive memory challenges

In line with prior research, children with autism had more difficulty remembering faces than typically developing children, the study found.

The research showed they also struggled to recall non-social information. On tests about sentences they read and non-social photos they viewed, their scores for immediate and delayed verbal recall, immediate visual recall, and delayed verbal recognition were lower.

“The study participants with autism had fairly high IQ, comparable to typically developing participants, but we still observed very obvious general memory impairments in this group,” said Liu, adding that the research team had not anticipated such large differences.

Among typically developing children, memory skills were consistent. If a child had a good memory for faces, he or she was also good at remembering non-social information.

This wasn’t the case in children with autism. “Among children with autism, some kids seem to have both impairments and some have more severe impairment in one area of memory or the other,” Liu said.

The researchers had not expected this result, either.

“It was a surprising finding that these two dimensions of memory are both dysfunctional, in ways that seem to be unrelated — and that maps onto our analysis of the brain circuitry,” Menon said.

The brain scans showed that, among the children with autism, distinct brain networks drive different types of memory difficulty.

For children with autism, the ability to retain non-social memories was predicted by connections in a network centered on the hippocampus — a small structure deep inside the brain that is known to regulate memory. But face memory in kids with autism was predicted by a separate set of connections centered on the posterior cingulate cortex, a key region of the brain’s default mode network, which has roles in social cognition and distinguishing oneself from other people.

“The findings suggest that general and face-memory challenges have two underlying sources in the brain which contribute to a broader profile of memory impairments in autism,” Menon said.

In both networks, the brains of children with autism showed over-connected circuits relative to typically developing children. Over-connectivity — likely due to too little selective pruning of neural circuits — has been found in other studies of brain networks in children with autism.

New autism therapies should account for the breadth of memory difficulties the research uncovered, as well as how these challenges affect social skills, Menon said. “This is important for functioning in the real world and for academic settings.”

Reference: “Replicable Patterns of Memory Impairments in Children With Autism and Their Links to Hyperconnected Brain Circuits” by Jin Liu, Lang Chen, Hyesang Chang, Jeremy Rudoler, Ahmad Belal Al-Zughoul, Julia Boram Kang, Daniel A. Abrams and Vinod Menon, 15 May 2023, Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging.

DOI: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2023.05.002

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and by the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute.

Be the first to comment on "Beyond Faces: Stanford Study Reveals Broader Memory Challenges in Children With Autism"