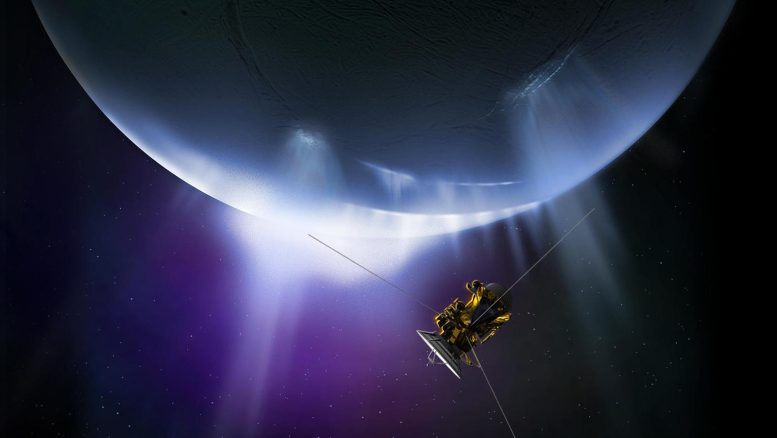

Artist’s impression of the Cassini spacecraft flying through plumes erupting from the south pole of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. These plumes are much like geysers and expel a combination of water vapor, ice grains, salts, methane, and other organic molecules. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Phosphorus, a key chemical element for many biological processes, has been found in icy grains emitted by the small moon and is likely abundant in its subsurface ocean.

Phosphorus, a vital element for life, has been discovered in icy grains emitted from Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, by NASA’s Cassini mission. This first-time discovery in an ocean beyond Earth hints at the potential for life-supporting conditions in Enceladus’ subsurface ocean and possibly other icy ocean worlds. However, the presence of life is yet to be confirmed.

Using data collected by NASA’s Cassini mission, an international team of scientists has discovered phosphorus – an essential chemical element for life – locked inside salt-rich ice grains ejected into space from Enceladus.

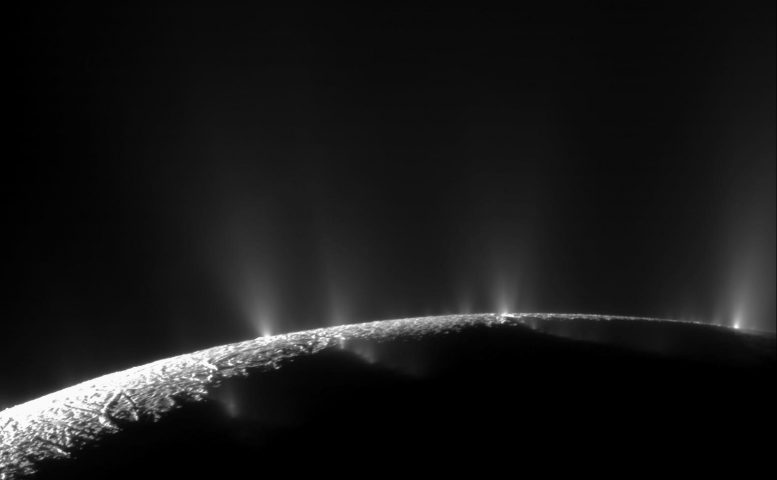

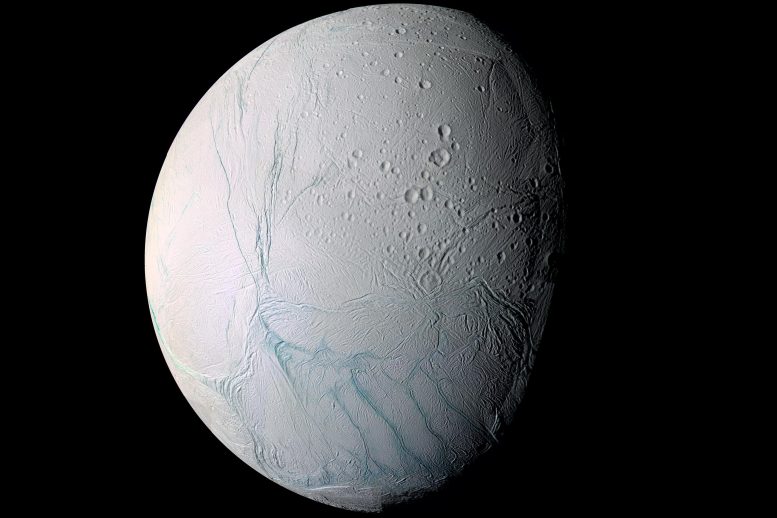

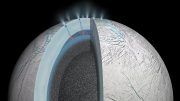

The small moon is known to possess a subsurface ocean, and water from that ocean erupts through cracks in Enceladus’ icy crust as geysers at its south pole, creating a plume. The plume then feeds Saturn’s E ring (a faint ring outside of the brighter main rings) with icy particles.

A dramatic plume sprays water ice and vapor from the south polar region of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Cassini’s fist hint of this plume came during the spacecraft’s first close flyby of the icy moon on February 17, 2005. Credits: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

During its mission at the gas giant from 2004 to 2017, Cassini flew through the plume and E ring numerous times. Scientists found that Enceladus’ ice grains contain a rich array of minerals and organic compounds – including the ingredients for amino acids – associated with life as we know it.

Phosphorus, the least abundant of the essential elements necessary for biological processes, hadn’t been detected until now. The element is a building block for DNA, which forms chromosomes and carries genetic information, and is present in the bones of mammals, cell membranes, and ocean-dwelling plankton. Phosphorus is also a fundamental part of energy-carrying molecules present in all life on Earth. Life wouldn’t be possible without it.

Seen as a bright arc in this 2006 observation by Cassini, Saturn’s E ring is fed with icy particles from Enceladus’ plume, creating wispy fingers of bright material that is backlit by the Sun. The shadowed hemisphere of the moon can be seen as a dark dot inside the ring. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

“We previously found that Enceladus’ ocean is rich in a variety of organic compounds,” said Frank Postberg, a planetary scientist at Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, who led the new study, published on June 14, in the journal Nature. “But now, this new result reveals the clear chemical signature of substantial amounts of phosphorus salts inside icy particles ejected into space by the small moon’s plume. It’s the first time this essential element has been discovered in an ocean beyond Earth.”

Previous analysis of Enceladus’ ice grains revealed concentrations of sodium, potassium, chlorine, and carbonate-containing compounds, and computer modeling suggested the subsurface ocean is of moderate alkalinity – all factors that favor habitable conditions.

Enceladus and Beyond

For this latest study, the authors accessed the data through NASA’s Planetary Data System, a long-term archive of digital data products returned from the agency’s planetary missions. The archive is actively managed by planetary scientists to help ensure its usefulness and usability by the worldwide planetary science community.

The authors focused on data collected by Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer instrument when it sampled icy particles from Enceladus in Saturn’s E ring. Many more ice particles were analyzed when Cassini flew through the E ring than when it went through just the plume, so the scientists were able to examine a much larger number of compositional signals there. By doing this, they discovered high concentrations of sodium phosphates – molecules of chemically bound sodium, oxygen, hydrogen, and phosphorus – inside some of those grains.

During a 2005 flyby, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft took high-resolution images of Enceladus that were combined into this mosaic, which shows the long fissures at the moon’s south pole that allow water from the subsurface ocean to escape into space. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Co-authors in Europe and Japan then carried out laboratory experiments to show that Enceladus’ ocean has phosphorus, bound inside different water-soluble forms of phosphate, in concentrations of at least 100 times that of our planet’s oceans. Further geochemical modeling by the team demonstrated that an abundance of phosphate may also be possible in other icy ocean worlds in the outer solar system, particularly those that formed from primordial ice containing carbon dioxide, and where liquid water has easy access to rocks.

“High phosphate concentrations are a result of interactions between carbonate-rich liquid water and rocky minerals on Enceladus’ ocean floor and may also occur on a number of other ocean worlds,” said co-investigator Christopher Glein, a planetary scientist and geochemist at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. “This key ingredient could be abundant enough to potentially support life in Enceladus’ ocean; this is a stunning discovery for astrobiology.”

Although the science team is excited that Enceladus has the building blocks for life, Glein stressed that life has not been found on the moon – or anywhere else in the solar system beyond Earth: “Having the ingredients is necessary, but they may not be sufficient for an extraterrestrial environment to host life. Whether life could have originated in Enceladus’ ocean remains an open question.”

Cassini’s mission came to an end in 2017, with the spacecraft burning up in Saturn’s atmosphere, but the trove of data it collected will continue to be a rich resource for decades to come. When it was launched, Cassini’s mission was to explore Saturn, its rings, and moons. The flagship mission’s array of instruments ended up making discoveries that continue to impact far more than planetary science.

“This latest discovery of phosphorus in Enceladus’ subsurface ocean has set the stage for what the habitability potential might be for the other icy ocean worlds throughout the solar system,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, who was not involved in the study. “Now that we know so many of the ingredients for life are out there, the question becomes: Is there life beyond Earth, perhaps in our own solar system? I feel that Cassini’s enduring legacy will inspire future missions that might, eventually, answer that very question.”

For more on this discovery:

- Critical Ingredient for Life Discovered at Saturn’s Moon Enceladus

- First Direct Evidence of Phosphorus on an Extraterrestrial Ocean World

- Study Proves Existence of Key Element for Life in the Outer Solar System

Reference: “Detection of phosphates originating from Enceladus’s ocean” by Frank Postberg, Yasuhito Sekine, Fabian Klenner, Christopher R. Glein, Zenghui Zou, Bernd Abel, Kento Furuya, Jon K. Hillier, Nozair Khawaja, Sascha Kempf, Lenz Noelle, Takuya Saito, Juergen Schmidt, Takazo Shibuya, Ralf Srama and Shuya Tan, 14 June 2023, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05987-9

More About the Mission

The Cassini-Huygens mission was a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency), and the Italian Space Agency. JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, managed the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. JPL designed, developed, and assembled the Cassini orbiter.

There are at least two reasons this is huge.

First, it makes Enceladus the prime site for astrobiology research. Second, it turns the usual biochemistry ideas of protocell evolution on its head. The minor biochemist part of astrobiology research has maintained that organic orthophosphates shouldn’t be around in the global ocean all other data says it evolved in.

On the first, Carolyn Porko notes:

“The finding makes Enceladus “the most promising place, the lowest-hanging fruit, in our solar system to search for extraterrestrial life,” Carolyn Porco, a planetary scientist who was not involved in the research, tells National Geographic’s Charles Q. Choi.” [Smithsonian Magazine]

On the second, the team notes:

Still, the team was not sure how Enceladus had gotten such high amounts of phosphates in the first place. So, they performed some lab experiments that suggested the moon’s ocean hosts lots of dissolved carbonates, just like soda. In this way, the so-called soda ocean can dissolve phosphate-filled rocks, leading to the high concentrations of phosphates in the water, per the New York Times’ Katrina Miller. “No one would be surprised if there’s phosphate in the rock of Enceladus. There’s phosphates on comets … it is not a big deal,” Postberg tells Space.com. “The big deal is that it is dissolved in the ocean, and with that, [it’s] readily available for the potential formation of life.”” [Smithsonian Magazine]

I should add for clarity that the early Earth ocean was likely dominantly acidic (precisely because of the CO2 dissolved from the atmosphere). But the early crust turnover produced local alkaline hydrothermal vent systems analogous to what we see today. Closer to mantle upwelling (today in the ocean: MORBs) the hydrothermal vents are acidic while they leach out hydrogen and iron, but then the crust modifies towards less iron compounds further away along a crustal dynamic ocean floor the vents are alkaline.