Ubiquitin plays a crucial role in cellular processes by regulating protein stability, but USP28 inhibitors, aimed at inhibiting cancer growth, also affect USP25, causing significant side effects. Researchers at the University of Würzburg discovered why USP28 and USP25 inhibitors are non-specific and are now working on developing more precise inhibitors.

Ubiquitin-related enzymes USP28 and USP25 play critical roles in cell processes, but their similar structures lead to challenges in cancer treatment with current inhibitors. Research at the University of Würzburg aims to refine these inhibitors to target more specifically and reduce side effects.

Ubiquitin, a small protein, plays a crucial role in nearly every cellular process by regulating the stability and function of most proteins. When ubiquitin attaches to other proteins, it typically marks them for degradation. However, this process can be reversed by specific enzymes. One such enzyme, USP28, helps stabilize proteins that are essential for cell growth and division, which can also contribute to the development of cancer.

In order to reduce the stability of these proteins and thus inhibit cancer growth, inhibitors of USP28 have been developed. These inhibitors, which form the basis of many anti-cancer drugs currently in development, disrupt cell division by blocking the USP28 enzyme. The problem is that they often act not only against USP28 but also against USP25, a closely related enzyme that separates ubiquitin from other proteins and is considered a key protein of the immune system. Further development of USP28 inhibitors into therapeutics that can be used in the clinic is therefore very difficult because of the foreseeable side effects – ranging from gastrointestinal problems to nerve damage and even autoimmune diseases.

Risk of Confusion Between the Two Enzymes

Researchers at the University of Würzburg (JMU) have now discovered why inhibitors not only target USP28, but also USP25: “Apparently, there is a high risk of confusion between USP28 and USP25,” explains Caroline Kisker, Chair of Structural Biology at the Rudolf Virchow Centre in Würzburg and Vice President for Research and Young Scientists. “We have been able to show that the two enzymes are very similar or even identical in many areas, including precisely where the inhibitors act.”

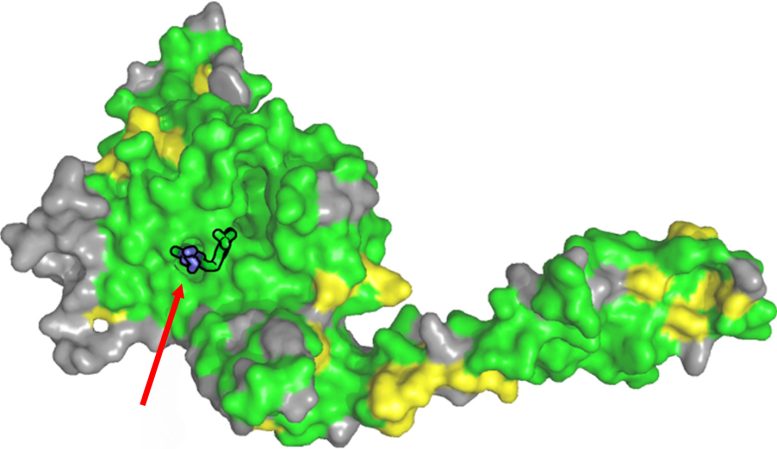

The structure of USP28 in complex with the inhibitor AZ1. All amino acids that are similar (yellow) or identical (green) to USP25 are highlighted. In particular, the region where the inhibitor binds (marked with a red arrow) is identical in both proteins. Credit: Kisker/JMU

As part of her research, the biochemist’s team used X-ray crystallography to analyze the structure of USP28 in combination with the three inhibitors “AZ1,” “Vismodegib” and “FT206” – and thus determine the spatial binding site. Further biochemical experiments on USP25 showed that the sites where the inhibitors bind to USP28 and USP25 are identical. “The inhibitors are therefore unable to distinguish where they bind,” says Kisker. “This explains the non-specific effect.”

Discovery Paves the Way for the Development of Precise Inhibitors

The new scientific findings provide an important basis for the search for more specific drugs with fewer side effects. Their development is the next major goal of the Würzburg researchers. “Our structural biology data allows us to modify existing inhibitors so that they only work against either USP25 or USP28,“ says Kisker. “We also want to look for inhibitors that bind to less similar enzyme sites. This will give these molecules greater targeting precision.”

Reference: “Structural basis for the bi-specificity of USP25 and USP28 inhibitors” by Jonathan Vincent Patzke, Florian Sauer, Radhika Karal Nair, Erik Endres, Ewgenij Proschak, Victor Hernandez-Olmos, Christoph Sotriffer and Caroline Kisker, 30 May 2024, EMBO Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s44319-024-00167-w

The research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Be the first to comment on "Cancer’s Molecular Achilles Heel: Key to Improving Cancer Treatments Discovered"