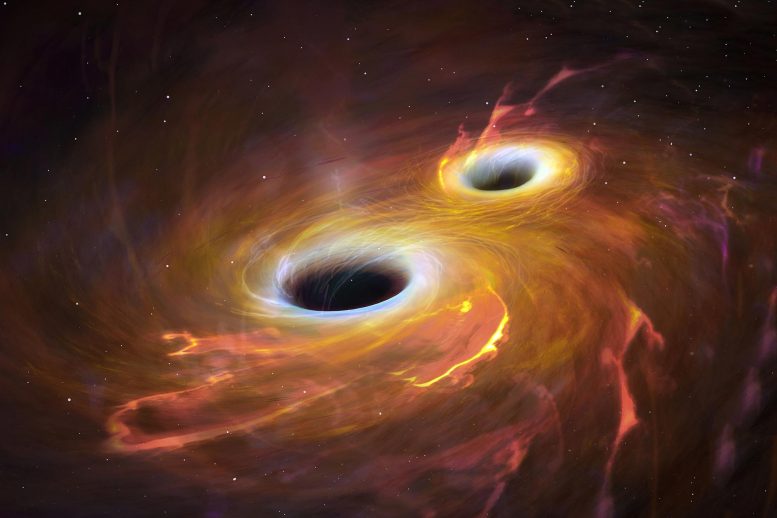

An artist’s impression of two black holes about to collide and merge.

Mysterious and inescapable, black holes rank among the most extraordinary entities in the universe. Scientists at HITS, Germany, have predicted that the ‘chirp’ noise generated when two black holes merge preferentially occurs in two universal frequency ranges.

The 2015 detection of gravitational waves, a phenomenon Einstein had hypothesized a century earlier, paved the way for the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics and initiated the dawn of gravitational-wave astronomy. The merger of two stellar-mass black holes releases gravitational waves with escalating frequency, known as the chirp signal, which can be detected on Earth. By analyzing the progression of this frequency (the chirp), scientists can calculate the “chirp mass,” a mathematical representation of the combined mass of the two black holes.

So far, it has been assumed that the merging black holes can have any mass. The team’s models, however, suggest that some black holes come in standard masses that then result in universal chirps.

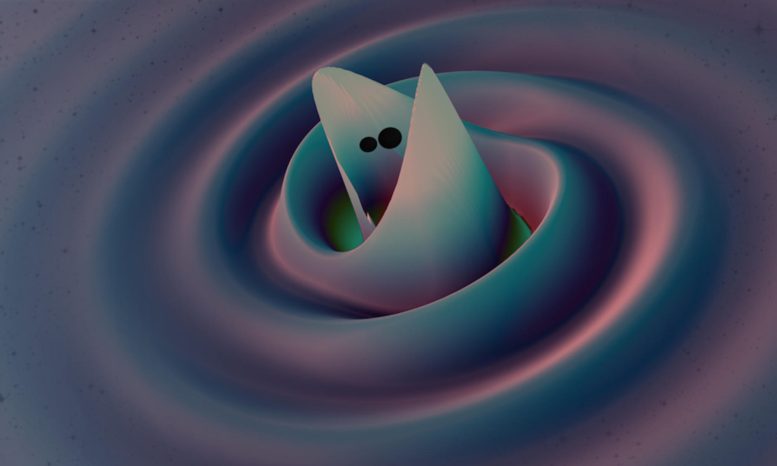

Ripples in the spacetime around a merging binary black-hole system from a numerical relativity simulation. Credit: Deborah Ferguson, Karan Jani, Deirdre Shoemaker, Pablo Laguna, Georgia Tech, MAYA Collaboration

“The existence of universal chirp masses not only tells us how black holes form,” says Fabian Schneider, who led the study at HITS, “it can also be used to infer which stars explode in supernovae.”Apart from that it provides insights into the supernova mechanism, uncertain nuclear and stellar physics, and provides a new way for scientists to measure the accelerated cosmological expansion of the Universe.

“Severe consequences for the final fates of stars”

Stellar-mass black holes with masses of approximately 3-100 times our Sun are the endpoints of massive stars that do not explode in supernovae but collapse into black holes. The progenitors of black holes that lead to mergers are originally born in binary star systems and experience several episodes of mass exchange between the components: in particular, both black holes are from stars that have been stripped off their envelopes.

“The envelope stripping has severe consequences for the final fates of stars. For example, it makes it easier for stars to explode in a supernova and it also leads to universal black hole masses as now predicted by our simulations,” says Philipp Podsiadlowski from Oxford University, second author of the study and currently Klaus Tschira Guest Professor at HITS.

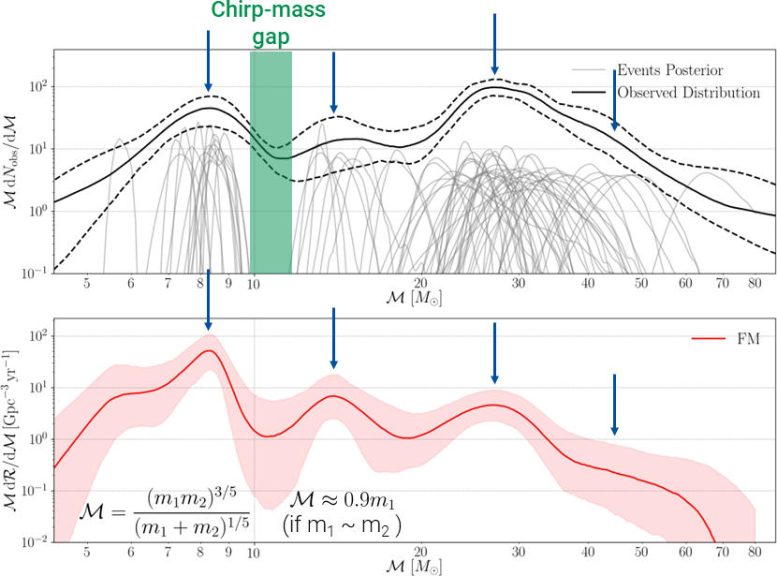

Distribution of the chirp masses of all binary black-hole mergers observed today. The top panel shows the raw data and probability distributions of the chirp masses of each individual event while the bottom panel shows a model inferred from the combined observations. The gap in chirp masses at 10–12 solar masses and the so-far identified features at about 8, 14, 27, and 45 solar masses are indicated. Figure reproduced from Abbott et al. 2021. Credit: Abbott et al., 2021.

The “stellar graveyard” – a collection of all known masses of the neutron star and black-hole remains of massive stars – is quickly growing thanks to the ever-increasing sensitivity of the gravitational-wave detectors and ongoing searches for such objects. In particular, there seems to be a gap in the distribution of the chirp masses of merging binary black holes, and evidence emerges for the existence of peaks at roughly 8 and 14 solar masses. These features correspond to the universal chirps predicted by the HITS team.

“Any features in the distributions of black-hole and chirp masses can tell us a great deal about how these objects have formed,” says Eva Laplace, the study’s third author.

Not in our galaxy: Black holes with much larger masses

Ever since the first discovery of merging black holes, it became evident that there are black holes with much larger masses than the ones found in our Milky Way. This is a direct consequence of these black holes originating from stars born with a chemical composition different from that in our Milky Way Galaxy. The HITS team could now show that – regardless of the chemical composition – stars that become envelope-stripped in close binaries form black holes of <9 and >16 solar masses but almost none in between.

In merging black holes, the universal black-hole masses of approximately 9 and 16 solar masses logically imply universal chirp masses, i.e. universal sounds. “When updating my lecture on gravitational-wave astronomy, I realized that the gravitational-wave observatories had found first hints of an absence of chirp masses and an overabundance at exactly the universal masses predicted by our models,” says Fabian Schneider. “Because the number of observed black-hole mergers is still rather low, it is not clear yet whether this signal in the data is just a statistical fluke or not.”

Whatever the outcome of future gravitational-wave observations: the results will be exciting and help scientists understand better where the singing black holes in this ocean of voices come from.

Reference: “Bimodal Black Hole Mass Distribution and Chirp Masses of Binary Black Hole Mergers” by Fabian R. N. Schneider, Philipp Podsiadlowski and Eva Laplace, 15 June 2023, The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/acd77a

The study was funded by the H2020 European Research Council.

Be the first to comment on "Echoes Across Space: The Universal Sound of Black Holes"