Overview of an area near Fukushima used for temporary storage of contaminated land. Credit: Evrard et al., SOIL 2019

Following the accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in March 2011, the Japanese authorities decided to carry out major decontamination works in the affected area, which covers more than 9,000 km2 (3,500 m2). On December 12, 2019, with most of this work having been completed, the scientific journal SOIL of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) is publishing a synthesis of approximately sixty scientific publications that together provide an overview of the decontamination strategies used and their effectiveness, with a focus on radiocesium. This work is the result of an international collaboration led by Olivier Evrard, researcher at the Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement [Laboratory of Climate and Environmental Sciences] (LSCE – CEA/CNRS/UVSQ, Université Paris Saclay).

Overview of a decontaminated area used for flower recultivation experiments. Credit: Evrard et al., SOIL 2019

Soil decontamination, which began in 2013 following the accident at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant, has now been nearly completed in the priority areas identified[1]. Indeed, areas that are difficult to access have not yet been decontaminated, such as the municipalities located in the immediate vicinity of the nuclear power plant. Olivier Evrard, a researcher at the Laboratory of Climate and Environmental Sciences and coordinator of the study (CEA/CNRS/UVSQ), in collaboration with Patrick Laceby of Alberta Environment and Parks (Canada) and Atsushi Nakao of Kyoto Prefecture University (Japan), compiled the results of approximately sixty scientific studies published on the topic.

This synthesis focuses mainly on the fate of radioactive cesium in the environment because this radioisotope was emitted in large quantities during the accident, contaminating an area of more than 9,000 km2 (3,500 m2). In addition, since one of the cesium isotopes (137Cs) has a half-life of 30 years, it constitutes the highest risk to the local population in the medium and long term, as it can be estimated that in the absence of decontamination it will remain in the environment for around three centuries. “The feedback on decontamination processes following the Fukushima nuclear accident is unprecedented,” according to Olivier Evrard, “because it is the first time that such a major clean-up effort has been made following a nuclear accident. The Fukushima accident gives us valuable insights into the effectiveness of decontamination techniques, particularly for removing cesium from the environment.”

Overview of a decontaminated area used for rice recultivation experiments. Credit: Evrard et al., SOIL 2019

This analysis provides new scientific lessons on decontamination strategies and techniques implemented in the municipalities affected by the radioactive fallout from the Fukushima accident. This synthesis indicates that removing the surface layer of the soil to a thickness of 5 cm (2 in), the main method used by the Japanese authorities to clean up cultivated land, has reduced cesium concentrations by about 80% in treated areas. Nevertheless, the removal of the uppermost part of the topsoil, which has proved effective in treating cultivated land, has cost the Japanese state about €24 billion. This technique generates a significant amount of waste, which is difficult to treat, transport, and store for several decades in the vicinity of the power plant, a step that is necessary before it is shipped to final disposal sites located outside Fukushima prefecture by 2050. By early 2019, Fukushima’s decontamination efforts had generated about 20 million cubic meters of waste.

Decontamination activities have mainly targeted agricultural landscapes and residential areas. The review points out that the forests have not been cleaned up – because of the difficulty and very high costs that these operations[2] would represent – as they cover 75% of the surface area located within the radioactive fallout zone. These forests constitute a potential long-term reservoir of radiocesium, which can be redistributed across landscapes as a result of soil erosion, landslides, and floods, particularly during typhoons that can affect the region between July and October. Atsushi Nakao, co-author of the publication, stresses the importance of continuing to monitor the transfer of radioactive contamination at the scale of coastal watersheds that drain the most contaminated part of the radioactive fallout zone. This monitoring will help scientists understand the fate of residual radiocesium in the environment in order to detect possible recontamination of the remediated areas due to flooding or intense erosion events in the forests.

The analysis recommends further research on:

- the issues associated with the recultivation of decontaminated agricultural land[3],

- the monitoring of the contribution of radioactive contamination from forests to the rivers that flow across the region,

- and the return of inhabitants and their reappropriation of the territory after evacuation and decontamination.

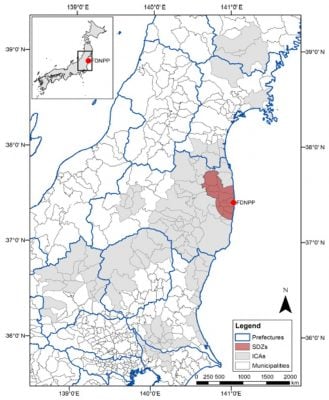

Map of Fukushima prefecture (showing the special decontamination zone, SDZ, delineated in red) and the intensive contamination areas where monitoring is conducted (ICAs, grey areas). FDNPP: Fukushima. Credit: Evrard et al., SOIL 2019

This research will be the subject of a Franco-Japanese and multidisciplinary international research project, MITATE (Irradiation Measurement Human Tolerance viA Environmental Tolerance), led by the CNRS in collaboration with various French (including the CEA) and Japanese organizations, which will start on January 1, 2020, for an initial period of 5 years.

Complementary approaches

This research is complementary to the project to develop bio- and eco-technological methods for the rational remediation of effluents and soils, in support of a post-accident agricultural rehabilitation strategy (DEMETERRES), led by the CEA, and conducted in partnership with INRA and CIRAD Montpellier.

Decontamination techniques

- In cultivated areas within the special decontamination zone, the surface layer of the soil was removed to a depth of 5 cm (2 in) and replaced with a new “soil” made of crushed granite available locally. In areas further from the plant, substances known to fix or substitute for radiocesium (potassium fertilizers, zeolite powders) have been applied to the soil.

- As far as woodland areas are concerned, only those that were within 20 meters of the houses were treated (cutting branches and collecting litter).

- Residential areas were also cleaned (ditch cleaning, roof and gutter cleaning, etc.), and (vegetable) gardens were treated as cultivated areas.

1 In Fukushima prefecture and the surrounding prefectures, the decision to decontaminate the landscapes affected by the radioactive fallout was made in November 2011 for 11 districts that were evacuated after the accident (special decontamination zone – SDZ – 1,117 km2 or 431 m2) and for 40 districts affected by lower, but still significant levels of radioactivity and that had not been evacuated in 2011 (areas of intensive monitoring of the contamination – ICA, 7,836 km2 or 3,025 m2).

2 128 billion euros according to one of the studies appearing in the review to be published on December 12, 2019, in SOIL.

3 Relating to soil fertility and the transfer of radiocesium from the soil to plants, for example.

This research is presented in the paper “Effectiveness of landscape decontamination following the Fukushima nuclear accident: a review” published in the EGU open access journal SOIL on December 12, 2019.

Reference: “Effectiveness of landscape decontamination following the Fukushima nuclear accident: a review” by Olivier Evrard, J. Patrick Laceby and Atsushi Nakao, 12 December 2019, SOIL.

DOI: 10.5194/soil-5-333-2019

The study was conducted by Olivier Evrard (Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement (LSCE/IPSL), Unité Mixte de Recherche 8212 (CEA/CNRS/UVSQ), Université Paris-Saclay), J. Patrick Laceby (Environmental Monitoring and Science Division (EMSD), Alberta Environment and Parks (AEP)), and Atsushi Nakao (Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Kyoto Prefectural University).

We have real experience and real suggestions for cleaning the soil in Fukushima. This is stated in my book.

https://www.amazon.com/%D0%A2%D0%B5%D1%85%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B5-%D0%B0%D1%81%D0%BF%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82%D1%8B-%D0%BF%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B4%D1%8F%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B9-%D0%BF%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%BC%D1%8B-Russian/dp/6200095841

Unfortunately, it does not receive development.

I thought certain fungi were known to concentrate certain radioactive isotopes. Could this not be exploited in some way to help?