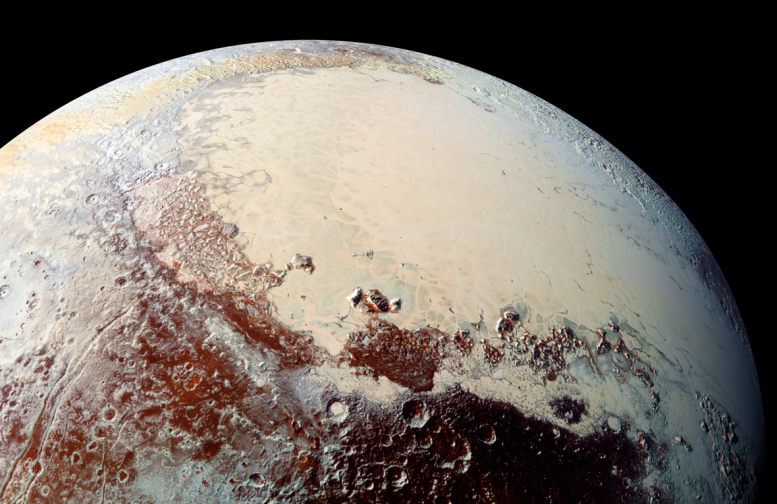

This high-resolution image captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft combines blue, red, and infrared images taken by the Ralph/Multispectral Visual Imaging Camera (MVIC). Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft made history this year giving us a close-up view of Pluto for the first time. Now it will start the New Year some 125 million miles (200 million kilometers) beyond Pluto, far removed from the excitement and activity that accompanied its historic flight through the Pluto system just five months ago.

The intrepid probe continues to send volumes of pictures and other data from the July 14 encounter – stashed on its digital recorders – over a radio link to Earth stretching billions of miles. As the pictures reach home, they remind us that 2015 was the year a small world on the planetary frontier captured our imagination, thanks to an inspired team of government, academic, and commercial partners determined to expand the frontiers of science and explore an entirely new realm of the solar system.

“The year 2015 had been in our team’s future for so long, it’s hard to believe that it’s soon to be in our past,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado. “But what a year it was – we explored Pluto, and made history doing it; we found that small planets can be as complex as big ones like Mars.”

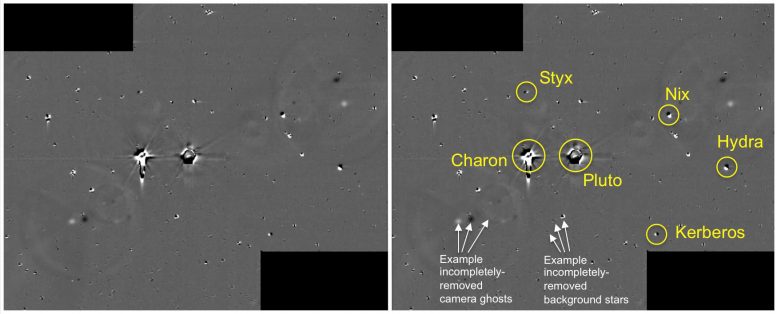

This movie was made from images taken January 25-31, 2015, as part of a New Horizons optical navigation campaign to better refine the locations of Pluto and Charon in preparation for the spacecraft’s close encounter with the small planet and its five moons. Credit: NASA/APL/SwRI

As the Encounter Began . . .

New Horizons began its long-awaited encounter with Pluto in January – nine years after launch – entering the first of several approach phases that culminated with the first close-up flyby of the Pluto system six months later.

A long-range photo shoot that began January 25 provided mission scientists with a continually improving look at the dynamics of Pluto and its moons – and those images played a critical role in navigating the spacecraft across the remaining 135 million miles (220 million kilometers) to Pluto, and helping mission scientists search for debris that might have impeded New Horizons at flyby.

Over the next few months, the onboard Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (known as LORRI) took hundreds of pictures of Pluto against star fields to refine the team’s estimates of New Horizons’ distance to Pluto. Though the Pluto system resembled little more than bright dots in the camera’s view until May, mission navigators used those pictures to design course-correction maneuvers and aim the spacecraft toward its flyby target point.

In April the team added several significant observations of the Pluto system, including the first color and spectral observations of Pluto and its moons, and the first ultraviolet observations to study the surface and atmosphere of Pluto and the surface of its largest moon, Charon. New Horizons also started the series of long-exposure images designed to help the team spot additional moons or rings in the Pluto system – which they never found.

After seven weeks of detailed searches for dust clouds, rings, and other potential hazards, the New Horizons team decided the spacecraft would remain on its original path through the Pluto system instead of making a late course correction to detour around any hazards. Because New Horizons was traveling at approximately 31,000 miles (about 50,000 kilometers) per hour, a particle as small as a grain of rice could have been lethal.

This illustration shows some of the final images used to determine that the coast was clear for New Horizons’ flight through the Pluto system. These images show the difference between two sets of 48 combined 10-second exposures with the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), taken June 26, 2015, from a range of 21.5 million kilometers (approximately 13 million miles) to Pluto. Credit: NASA/APL/SwRI

A Mission Save

New Horizons had traveled farther than any spacecraft to reach its primary target — and while it spent about two-thirds of that long journey in hibernation, the team was designing and practicing every maneuver and science operation of the Pluto encounter, and getting to know its spacecraft inside and out.

That preparation paid off just before the flyby. On July 4, while attempting to process commands sent from home and compress stored science data at the same time, the spacecraft’s main computer overloaded and, as designed, switched to its backup processor. This put New Horizons into a “safe mode” where it stopped performing science, pointed to Earth, and quietly awaited word from operators on the next move.

The recovery was fast and thorough; mission engineers immediately identified the problem and reestablished contact within two hours. By July 7, the intricate set of flyby commands — the critical directions for New Horizons’ science instruments — was reloaded and ready to go.

“Looking back over the last year, there are many things that stand out, but the most revealing to me is the awesome power of a team,” said APL’s Alice Bowman, the New Horizons mission operations manager. “In my opinion, it was and continues to be the reason for the huge success of New Horizons. As exemplified by New Horizons, a team is so much more than the sum of its members.”

Celebrating Science and Exploration

New Horizons mission central, for the week of July 12-18, was the Kossiakoff Center at APL. Nearly 250 members of the media, 1,600 guests and hundreds of staff were on hand for panel discussions, press conferences, and related activities; a full NASA TV set was built on the auditorium floor for the flyby coverage that was broadcast and webcast to the world.

New Horizons was actually out of contact with Earth during its closest approach to Pluto at approximately 7:50 a.m. EDT on July 14. But the team, joined by guests and an international TV audience, marked the flyby with a raucous countdown that rivaled New Year’s Eve in Times Square. Network morning shows beamed live images of U.S. flags waving and cheers and hugs around the room. Later that morning the team revealed a stunning, immediately iconic image of Pluto, the last photo New Horizons took and transmitted before entering flyby silence.

But the most critical transmission on July 14 didn’t include a picture; it was the burst of telemetry, set to arrive in the New Horizons Mission Operations Center just before 9 p.m., indicating the spacecraft was healthy and did its job. The suspense was short-lived, as the transmission — sent from New Horizons more than four hours earlier — came right on time. “We have carrier lock,” announced mission operations chief Bowman, meaning NASA’s Deep Space Network had linked up to New Horizons.

Then came the telemetry, sparking applause in Mission Ops. After a quick poll of the spacecraft systems team— where all indicated New Horizons was “green” — Bowman made the call: “We have a healthy spacecraft, we have collected all the data, and we are outbound from Pluto.”

A jubilant Stern burst into the room, hugged Bowman, and started a cheer of “U-S-A, U-S-A” among the ops team. He was followed by APL Director Ralph Semmel, NASA Associate Administrator John Grunsfeld, and Administrator Charles Bolden, who all offered congratulations.

Bowman, after the hugs and handshakes, looked around the room. “This is just fantastic,” she said. “Just like we planned it, just like we practiced. We did it!”

Bowman then led the operations team on a walk to the packed auditorium, where they and the rest of the New Horizons team received a standing ovation to kick off a press conference that more resembled a Super Bowl celebration. All that was missing was a trophy and a call from the White House — though President Obama did tweet his congratulations to NASA and the team.

Pluto nearly fills the frame in this image from the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) aboard New Horizons, taken on July 13, 2015, when the spacecraft was 476,000 miles (768,000 kilometers) from the surface. This is the last and most detailed image sent to Earth before the spacecraft’s closest approach to Pluto on July 14. The color image has been combined with lower-resolution color information from the Ralph instrument that was acquired earlier on July 13. Credit: NASA/APL/SwRI

“Inspiration like that provided by New Horizons will keep interest strong for the next generation to make their own giant leaps,” Bolden said to open the press conference. “This is a historic win for science and exploration.”

The first close-up pictures, showing Pluto’s surface and some of its moons in incredible detail, came back the next day. Over the next several days the science team, camped out at APL since June, scoured data and images of Pluto that revealed nitrogen ice flowing across the surface, mountain ranges that rival the Rockies, and areas that might still be geologically active.

For science team member Fran Bagenal, of the University of Colorado, Boulder, the magical public reaction to the images of Pluto remains a favorite memory. “Pluto has always been a favorite planet for many people – particularly kids. But when I show the images to friends, relatives, and public audiences, everyone just smiles, shakes their heads, and says, ‘Wow! That’s so cool!’”

“I feel incredibly lucky to have been a part of this event that simultaneously brings to the end five decades of solar system ‘first’ explorations, and starts a new epoch of exploring further reaches of the solar system,” said Joel Parker, a New Horizons co-investigator from SwRI. “We didn’t even know that ‘third zone,’ the Kuiper Belt, existed when humans started to send spacecraft to explore the planets. It makes me wonder: What new places in our solar system will we discover in the next 50 years?”

Be the first to comment on "NASA Looks Back at the ‘Year of Pluto’"