Researchers found no significant differences in brain structure between the group participating in a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course and either control group.

A new study finds no indication of structural brain change with short-term mindfulness training

New evidence revealed in the mid-twentieth century that the brain might be “plastic,” and that experience could cause changes in the brain. Learning new skills, aerobic exercise, and balance training, are all activities that have been tied to plasticity.

However, it has remained unclear if mindfulness interventions, such as meditation, can change the structure of the brain. Some research conducted using the well-known eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course suggested that meditation might in fact alter brain structure. However, the scope and technology of that study were limited, and the elective participant pools may have skewed the results.

In a new study, a team led by Richard J. Davidson from the University of Wisconsin-Center Madison’s for Healthy Minds discovered no indication of structural brain changes following short-term mindfulness training.

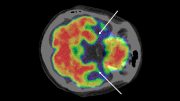

The team’s recent study, published in Science Advances, is the largest and most rigorously controlled to date. In two novel trials, over 200 healthy participants with no meditation experience or mental health concerns were given MRI exams to measure their brains prior to being randomly assigned to one of three study groups: the eight-week MBSR course, a non-mindfulness-based well-being intervention called the Health Enhancement Program, or a control group that didn’t receive any type of training.

The MBSR course was taught by certified instructors and included mindfulness practices such as yoga, meditation, and body awareness. The HEP course was developed as an activity that is similar to MBSR but without mindfulness training. Instead, HEP engaged participants in exercise, music therapy, and nutrition practices. Both groups spent additional time in practice at home.

Following each eight-week trial, all participants were given a final MRI exam to measure changes in brain structure. Data from the two trials were pooled to create a large sample size. No significant differences in structural brain changes were detected between MBSR and either control group.

Participants were also asked to self-report on mindfulness following the study. Those in both the MBSR and HEP groups reported increased mindfulness compared with the control group, providing evidence that improvements in self-reported mindfulness may be related to benefits of any type of wellness intervention more broadly, rather than being specific to mindfulness meditation practice.

So, what about the prior study that found evidence of structural changes? Since participants in that study had sought out a course for stress reduction, they may have had more room for improvement than the healthy population studied here. In other words, according to the lead author of the new study, behavioral scientist and first author Tammi Kral, “the simple act of choosing to enroll in MBSR may be associated with increased benefit.” The current study also had a much larger sample size, increasing confidence in the findings.

However, as the team writes in the new paper, “it may be that only with much longer duration of training, or training explicitly focused on a single form of practice, that structural alterations will be identified.” Whereas structural brain changes are found with physical and spatial training, mindfulness training spans a variety of psychological areas like attention, compassion, and emotion. This training engages a complex network of brain regions, each of which may be changing to different degrees in different people — making overall changes at the group level difficult to observe.

These surprising results ultimately underscore the importance of scrutiny for positive findings and the need for verification through replication. In addition, studies of longer-term interventions as well as ones singularly focused on meditation practices may lead to different results. “We are still in the early stages of research on the effects of meditation training on the brain and there is much to be discovered,” says Davidson.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants P01AT004952, P50- MH084051, R01-MH43454, T32MH018931, P30 HD003352-449015, and U54 HD090256), the Fetzer Institute, John Templeton Foundation and a National Academy of Education/ Spencer Foundation postdoctoral fellowship.

Reference: “Absence of structural brain changes from mindfulness-based stress reduction: Two combined randomized controlled trials” by Tammi R. A. Kral, Kaley Davis, Cole Korponay, Matthew J. Hirshberg, Rachel Hoel, Lawrence Y. Tello, Robin I. Goldman, Melissa A. Rosenkranz, Antoine Lutz and Richard J. Davidson, 20 May 2022, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abk3316

Be the first to comment on "No Evidence of Structural Brain Change From Short-Term Meditation"