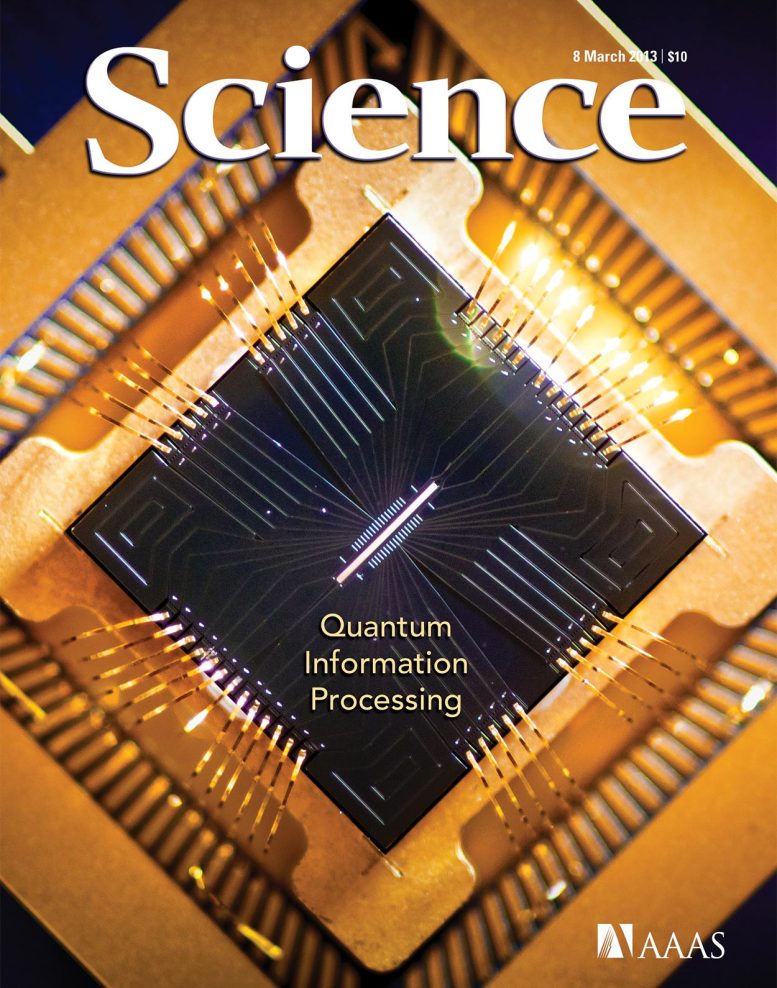

A silicon chip levitates individual atoms used in quantum information processing. Photo: Curt Suplee and Emily Edwards, Joint Quantum Institute and University of Maryland. Credit: Science

A newly published study looks at recent advances in quantum measurements, coherent control, and the generation of entangled states, while describing some of the challenges that remain ahead for quantum computing and other applications.

New technologies that exploit quantum behavior for computing and other applications are closer than ever to being realized due to recent advances, according to a review article published this week in the journal Science.

These advances could enable the creation of immensely powerful computers as well as other applications, such as highly sensitive detectors capable of probing biological systems. “We are really excited about the possibilities of new semiconductor materials and new experimental systems that have become available in the last decade,” said Jason Petta, one of the authors of the report and an associate professor of physics at Princeton University.

Petta co-authored the article with David Awschalom of the University of Chicago, Lee Basset of the University of California-Santa Barbara, Andrew Dzurak of the University of New South Wales and Evelyn Hu of Harvard University.

Two significant breakthroughs are enabling this forward progress, Petta said in an interview. The first is the ability to control quantum units of information, known as quantum bits, at room temperature. Until recently, temperatures near absolute zero were required, but new diamond-based materials allow spin qubits to be operated on a table top, at room temperature. Diamond-based sensors could be used to image single molecules, as demonstrated earlier this year by Awschalom and researchers at Stanford University and IBM Research (Science, 2013).

The second big development is the ability to control these quantum bits, or qubits, for several seconds before they lapse into classical behavior, a feat achieved by Dzurak’s team (Nature, 2010) as well as Princeton researchers led by Stephen Lyon, professor of electrical engineering (Nature Materials, 2012). The development of highly pure forms of silicon, the same material used in today’s classical computers, has enabled researchers to control a quantum mechanical property known as “spin”. At Princeton, Lyon and his team demonstrated the control of spin in billions of electrons, a state known as coherence, for several seconds by using highly pure silicon-28.

Quantum-based technologies exploit the physical rules that govern very small particles — such as atoms and electrons — rather than the classical physics evident in everyday life. New technologies based on “spintronics” rather than electron charge, as is currently used, would be much more powerful than current technologies.

In quantum-based systems, the direction of the spin (either up or down) serves as the basic unit of information, which is analogous to the 0 or 1 bit in a classical computing system. Unlike our classical world, an electron spin can assume both a 0 and 1 at the same time, a feat called entanglement, which greatly enhances the ability to do computations.

A remaining challenge is to find ways to transmit quantum information over long distances. Petta is exploring how to do this with collaborator Andrew Houck, associate professor of electrical engineering at Princeton. Last fall in the journal Nature, the team published a study demonstrating the coupling of a spin qubit to a particle of light, known as a photon, which acts as a shuttle for the quantum information.

Yet another remaining hurdle is to scale up the number of qubits from a handful to hundreds, according to the researchers. Single quantum bits have been made using a variety of materials, including electronic and nuclear spins, as well as superconductors.

Some of the most exciting applications are in new sensing and imaging technologies rather than in computing, said Petta. “Most people agree that building a real quantum computer that can factor large numbers is still a long ways out,” he said. “However, there has been a change in the way we think about quantum mechanics – now we are thinking about quantum-enabled technologies, such as using a spin qubit as a sensitive magnetic field detector to probe biological systems.”

Reference: “Quantum Spintronics: Engineering and Manipulating Atom-Like Spins in Semiconductors” by David D. Awschalom, Lee C. Bassett, Andrew S. Dzurak, Evelyn L. Hu and Jason R. Petta, 8 March 2013, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.1231364

brilliant work, I’ll be the first customer, don’t let me down 🙂