Microwave kinetic inductance detectors (MKIDs), which can simultaneously count photons, measure their energy, and record each one’s time of arrival, could eventually replace charge-coupled devices (CCDs) in telescopes.

Microwave kinetic inductance detectors (MKIDs), which can simultaneously count photons, measure their energy, and record each one’s time of arrival, could eventually replace charge-coupled devices (CCDs) in telescopes. CCDs can only do this after the light is split with a prism or grating, a step that adds to the loss of photons.

Ben Mazin, an astronomer at the University of California, Santa Barbara, presented his research at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas. The first results from an array of 1,024 MKIDs that was installed at the 5.1-meter telescope at Palomar Observatory in California were significant, as they captured individual photons with microsecond precision from the Crab Nebula. CCDs have read-out times that are too slow for such precise measurements.

Once MKIDs are scaled into bigger arrays, they could be useful to search for gravitational waves and extrasolar planets. The drawback of MKIDs is that they need to be cooled down to 100 millikelvin, making them difficult to use in small spaces, satellites, or in spacecraft.

Once MKIDs are scaled into bigger arrays, they could be useful to search for gravitational waves and extrasolar planets. The drawback of MKIDs is that they need to be cooled down to 100 millikelvin, making them difficult to use in small spaces, satellites, or in spacecraft.

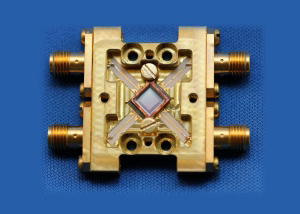

MKIDs rely on resonating circuits made of superconducting materials, allowing electrons to move in Cooper pairs bound by low-temperature quantum effects. When a photon strikes the circuit, it breaks apart one of these Cooper pairs, shifting the resonant frequency of the circuit, which indicates an energy loss.

The detectors were first invented by Jonas Smuidzinas, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, and his colleagues in 2003 for use in X-ray astronomy. A 2,000-pixel array of MKIDs will be deployed this year at the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory in Hawaii.

MKIDs could also detect the tiny variations in radio signals from millisecond pulsars, proving the existence of gravitational waves. They could also be used in the direct detection of extrasolar planets, allowing telescopes to skip the step of shunting light through a separate detector in adaptive optics and measuring the distortions directly.

Be the first to comment on "Superconducting Detectors Could Help Find Gravitational Waves and Extrasolar Planets"