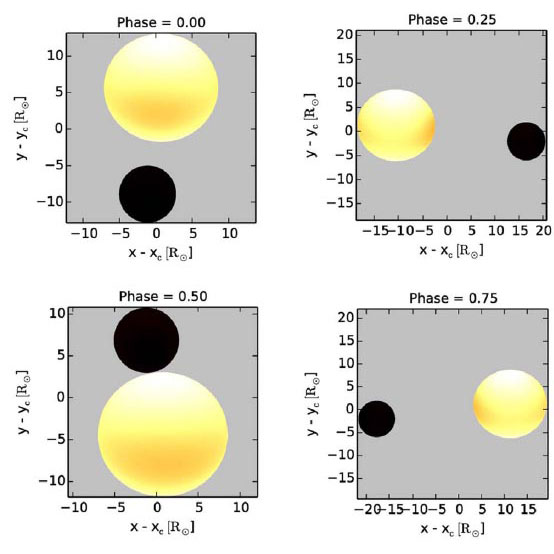

A schematic of the binary stars in Spica, showing four stages of an orbital period. Massive binary stars often have a “mass discrepancy problem,” meaning that the masses derived from orbital and evolutionary methods disagree.

A newly published study details Spica, an eccentric double-lined spectroscopic binary system with a β Cep type variable primary component.

The familiar star Spica (Alpha Virginis) is the fifteenth brightest star in the night sky, in part because it is relatively nearby, only about 250 light-years away. It is easy to find by following the arc of the Big Dipper’s handle and using the mnemonic, “Arc to Arcturus (Alpha Bootes) and then spike to Spica.” In fact Spica is a “spectroscopic” binary, two stars orbiting each other and too close together to separate visually. They were revealed as being a binary pair in 1890 when spectroscopic observations discovered that the stellar lines were doubled due to each star having a slightly different velocity and corresponding Doppler shift. The stars in Spica are, moreover, an unusual pair: They are very close, separated by about twenty-eight solar-radii, and orbit each other in only 4.01 days. This puts them so close together that their mutual gravity tidally distorts their atmospheres, with the result that the stars are not spherical. Oh, and the more massive star pulses in size and luminosity.

Binary stars play a critical role for astronomers studying stars. Because mass and gravity determine the dynamics of orbital behavior, in a binary system it is possible to get at the stars’ masses by studying the orbital motions, something that nominally can be done with great accuracy. In contrast, for a single star the mass must be inferred from a much more complicated set of stellar properties and evolutionary models, although even so these models are thought to be excellent and reliable. Sometimes, however, the mass determined from spectroscopy (kinematics) differs from that determined from evolutionary modeling. In the case of massive binary stars (and Spica’s two stars are both massive, at 11.4 and 7.2 solar-masses, respectively) this is known as the “mass discrepancy problem.”

Enter CfA astronomer Dimitar Sasselov who is part of a team trying to resolve the mass discrepancy problem. In previous work on massive binaries, the team found that the single-star evolutionary models were slightly in error, in particular for the smaller partner. For their analysis of Spica, the astronomers obtained 1731 high-quality spectra and broadband measurements over the course of nearly twenty-three days. They were able to refine all of the system parameters, and realized that the pulsations in the larger star are actually tidally induced, the first such case found for a massive binary. They also found, somewhat surprisingly, that there was no mass discrepancy problem for Spica – the stellar masses derived in both ways are actually consistent, although there are large uncertainties introduced by the complex nature of the Spica system. The research program continues, and the astronomers plan to observe and analyze another few dozen systems in a consistent way, to improve their insights into the nature of the mass discrepancy problem for massive stars.

Reference: “Stellar modeling of Spica, a high-mass spectroscopic binary with a β Cep variable primary component” 2 February 2016, MNRAS.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stw255

Be the first to comment on "Astronomers Gain a Better Understanding of Spica"