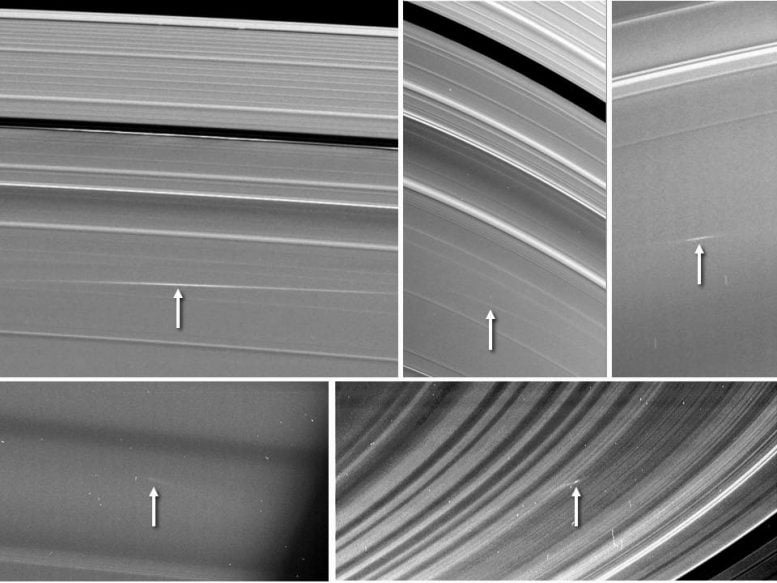

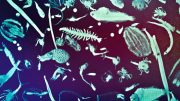

Five images of Saturn’s rings, taken by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft between 2009 and 2012, show clouds of material ejected from impacts of small objects into the rings. Clockwise from top left are two views of one cloud in the A ring, taken 24.5 hours apart, a cloud in the C ring, one in the B ring, and another in the C ring. Arrows in the annotated version point to the cloud structures, which spread out at visibly different angles than the surrounding ring features. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute/Cornell

Using NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, astronomers observed meteors colliding with Saturn’s rings.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has provided the first direct evidence of small meteoroids breaking into streams of rubble and crashing into Saturn’s rings.

These observations make Saturn’s rings the only location besides Earth, the moon, and Jupiter where scientists and amateur astronomers have been able to observe impacts as they occur. Studying the impact rate of meteoroids from outside the Saturnian system helps scientists understand how different planet systems in our solar system formed.

The solar system is full of small, speeding objects. These objects frequently pummel planetary bodies. The meteoroids at Saturn are estimated to range from about one-half inch to several yards (1 centimeter to several meters) in size. It took scientists years to distinguish tracks left by nine meteoroids in 2005, 2009 and 2012.

Details of the observations appear in a paper in the Thursday, April 25 edition of Science.

Results from Cassini have already shown Saturn’s rings act as very effective detectors of many kinds of surrounding phenomena, including the interior structure of the planet and the orbits of its moons. For example, a subtle but extensive corrugation that ripples 12,000 miles (19,000 kilometers) across the innermost rings tells of a very large meteoroid impact in 1983.

“These new results imply the current-day impact rates for small particles at Saturn are about the same as those at Earth — two very different neighborhoods in our solar system — and this is exciting to see,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “It took Saturn’s rings acting like a giant meteoroid detector — 100 times the surface area of the Earth — and Cassini’s long-term tour of the Saturn system to address this question.”

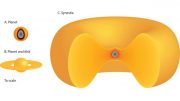

This animation depicts the shearing of an initially circular cloud of debris as a result of the particles in the cloud having differing orbital speeds around Saturn. After the cloud is formed, each particle within it follows its own simple orbit. The cloud begins to elongate as particles closer to the planet orbit at a faster speed than the particles farther from the planet. Scientists can use the angle the cloud was canted to infer the time elapsed since it was formed. This method was used to determine the times of the impacts that created the clouds in Saturn’s rings that were captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Credit: NASA/Cornell

The Saturnian equinox in summer 2009 was an especially good time to see the debris left by meteoroid impacts. The very shallow sun angle on the rings caused the clouds of debris to look bright against the darkened rings in pictures from Cassini’s imaging science subsystem.

“We knew these little impacts were constantly occurring, but we didn’t know how big or how frequent they might be, and we didn’t necessarily expect them to take the form of spectacular shearing clouds,” said Matt Tiscareno, lead author of the paper and a Cassini participating scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. “The sunlight shining edge-on to the rings at the Saturnian equinox acted like an anti-cloaking device, so these usually invisible features became plain to see.”

Tiscareno and his colleagues now think meteoroids of this size probably break up on a first encounter with the rings, creating smaller, slower pieces that then enter into orbit around Saturn. The impact into the rings of these secondary meteoroid bits kicks up the clouds. The tiny particles forming these clouds have a range of orbital speeds around Saturn. The clouds they form soon are pulled into diagonal, extended bright streaks.

“Saturn’s rings are unusually bright and clean, leading some to suggest that the rings are actually much younger than Saturn,” said Jeff Cuzzi, a co-author of the paper and a Cassini interdisciplinary scientist specializing in planetary rings and dust at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “To assess this dramatic claim, we must know more about the rate at which outside material is bombarding the rings. This latest analysis helps fill in that story with detection of impactors of a size that we weren’t previously able to detect directly.”

Reference: “Observations of Ejecta Clouds Produced by Impacts onto Saturn’s Rings” by Matthew S. Tiscareno, Colin J. Mitchell, Carl D. Murray, Daiana Di Nino, Matthew M. Hedman, Jürgen Schmidt, Joseph A. Burns, Jeffrey N. Cuzzi, Carolyn C. Porco, Kevin Beurle and Michael W. Evans, 26 April 2013, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.1233524

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, a division of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. JPL designed, developed and assembled the Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras. The imaging team consists of scientists from the United States, England, France, and Germany. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

Be the first to comment on "Cassini Observes Meteors Colliding With Saturn’s Rings"