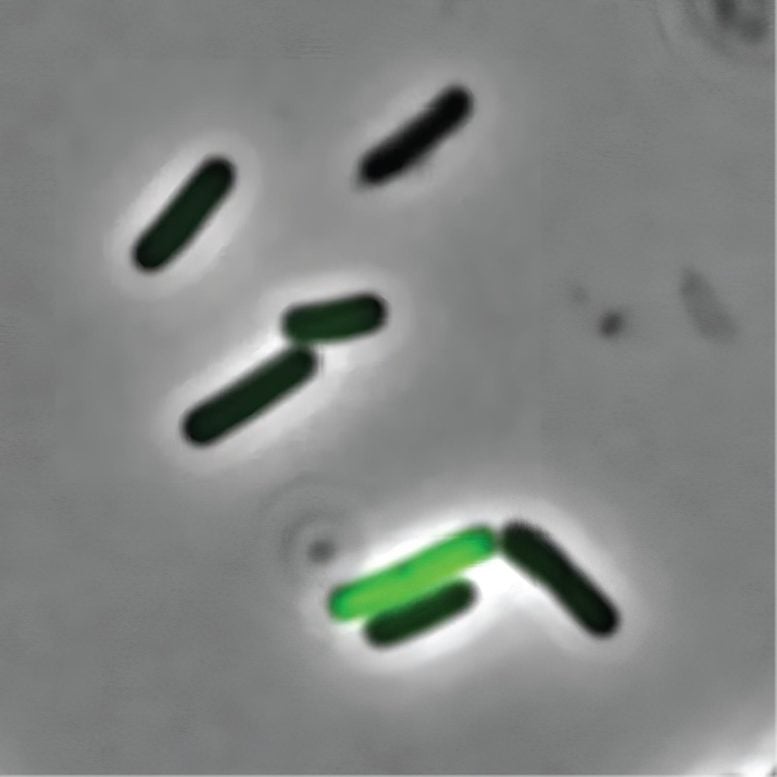

A fluorescent microscope image shows that in a population of genetically identical. The cell in green is expressing a green-fluorescent protein that is expressed by cells that are able to take up DNA from the environment. Credit: Adam Rosenthal et al.

According to the research findings of Dr. Adam Rosenthal, cells that are genetically identical within a bacterial community exhibit distinct functions. This means that certain members of the community exhibit more passive behavior while others produce the toxins that make us feel sick.

Have you ever experienced the sensation of becoming irritable due to extreme hunger, a state colloquially referred to as “hangry?” In a fascinating new study, Dr. Adam Rosenthal, an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, reveals that certain bacterial cells also exhibit a similar kind of “hanger,” resulting in the release of damaging toxins into our systems which can cause illness.

Adam Rosenthal, Ph.D. Credit: Adam Rosenthal

Working alongside collaborators from Harvard, Princeton, and Danisco Animal Nutrition, Rosenthal leveraged cutting-edge technology to ascertain that within a single bacterial colony, genetically identical cells can perform disparate roles. It appears that while some of these bacterial members remain relatively docile, others are responsible for the production of the very toxins that lead to sickness.

“Bacteria behave much more differently than we traditionally thought,” said Rosenthal. “Even when we study a community of bacteria that are all genetically identical, they don’t all act the same way. We wanted to find out why.”

The findings, published in Nature Microbiology, are particularly important in understanding how and why bacterial communities defer duties to certain cells – and could lead to new ways to tackle antibiotic tolerance further down the line.

Rosenthal decided to take a closer look into why some cells act as “well-behaved citizens” and others as “bad actors” that are tasked with releasing toxins into the environment. He selected Clostridium perfringens – a rod-shaped bacterium that can be found in the intestinal tract of humans and other vertebrates, insects, and soil – as his microbe of study.

With the help of a device called a microfluidic droplet generator, they were able to separate, or partition, single bacterial cells into droplets to decode every single cell.

They found that the C. perfringens cells that were not producing toxins were well-fed with nutrients. On the other hand, toxin-producing C. perfringens cells appear to be lacking those crucial nutrients.

“If we give more of these nutrients,” postulated Rosenthal, “maybe we can get the toxin-producing cells to behave a little bit better.”

Researchers then exposed the bad actor cells to a substance called acetate. Their hypothesis rang true. Not only did toxin levels drop across the community, but the number of bad actors reduced as well. But in the aftermath of such astounding results, even more questions are popping up.

Now that they know that nutrients play a significant role in toxicity, Rosenthal wonders if there are particular factors found in the environment that may be ‘turning on’ toxin production in other types of infections, or if this new finding is only true for C. perfringens.

Perhaps most importantly, Rosenthal theorizes that introducing nutrients to bacteria could provide a new alternative treatment for animals and humans, alike.

For example, the model organism Clostridium perfringens is a powerful foe in the hen house. As the food industry is shifting away from the use of antibiotics, poultry are left defenseless from the rapidly spreading, fatal disease. The recent findings from Rosenthal et al. may give farmers a new tool to reduce pathogenic bacteria without the use of antibiotics.

As for us humans, there is more work to be done. Rosenthal is in the process of partnering with colleagues across UNC to apply his recent findings to tackle antibiotic tolerance. Antibiotic tolerance occurs when some bacteria are able to dodge the drug target even when the community has not evolved mutations to make all cells resistant to an antibiotic. Such tolerance can result in a less-effective treatment, but the mechanisms controlling tolerance are not well understood.

In the meantime, Rosenthal will continue to research these increasingly complex bacterial communities to better understand why they do what they do.

Reference: “Probe-based bacterial single-cell RNA sequencing predicts toxin regulation” by Ryan McNulty, Duluxan Sritharan, Seong Ho Pahng, Jeffrey P. Meisch, Shichen Liu, Melanie A. Brennan, Gerda Saxer, Sahand Hormoz and Adam Z. Rosenthal, 3 April 2023, Nature Microbiology.

DOI: 10.1038/s41564-023-01348-4

Be the first to comment on "“Hangry” Bacteria – New Research Sheds Light on Unusual Behavior"