Image of lenticular galaxy NGC 1277 taken with Hubble Space Telescope. This small, flattened galaxy contains one of the most massive central black holes ever found. At 17 billion solar masses, the black hole weighs an extraordinary 14% of the total galaxy mass. Credit: NASA/ESA/Andrew C. Fabian

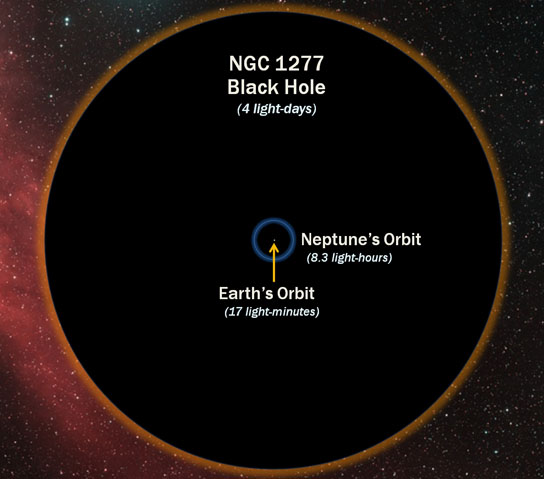

A massive black hole, measuring 17 billion times our sun’s mass and more than 11 times as wide as Neptune’s orbit around the sun, could change theories about how black holes and galaxies form and evolve.

Astronomers have used the Hobby-Eberly Telescope at The University of Texas at Austin’s McDonald Observatory to measure the mass of what may be the most massive black hole yet — 17 billion times our sun’s mass — in galaxy NGC 1277. The unusual black hole makes up 14 percent of its galaxy’s mass, rather than the usual 0.1 percent. This galaxy and several more in the same study could change theories about how black holes and galaxies form and evolve. The work is published in the journal Nature.

NGC 1277 lies 220 million light-years away in the constellation Perseus. The galaxy is only 10 percent the size and mass of our Milky Way. Despite NGC 1277’s diminutive size, the black hole at its heart is more than 11 times as wide as Neptune’s orbit around the sun.

“This is a really oddball galaxy,” said team member Karl Gebhardt of The University of Texas at Austin. “It’s almost all black hole. This could be the first object in a new class of galaxy-black hole systems.” Furthermore, the most massive black holes have been seen in giant blobby galaxies called “ellipticals,” but this one is seen in a relatively small lens-shaped galaxy (in astronomical jargon, a “lenticular galaxy”).

This diagram shows how the diamater of the 17-billion-solar-mass black hole in the heart of galaxy NGC 1277 compares with the orbit of Neptune around the Sun. The black hole is eleven times wider than Neptune’s orbit. Shown here in two dimensions, the “edge” of the black hole is actually a sphere. This boundary is called the “event horizon,” the point from beyond which, once crossed, neither matter nor light can return. Credit: D. Benningfield/K. Gebhardt/StarDate

The find comes out of the Hobby-Eberly Telescope Massive Galaxy Survey (MGS). The study’s goal is to better understand how black holes and galaxies form and grow together, a process that isn’t well understood.

“At the moment there are three completely different mechanisms that all claim to explain the link between black hole mass and host galaxies’ properties. We do not understand yet which of these theories is best,” said Nature lead author Remco van den Bosch, who began this work while holding the W.J. McDonald postdoctoral fellowship at The University of Texas at Austin. He is now at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

The problem is lack of data. Astronomers know the mass of fewer than 100 black holes in galaxies. But measuring black hole masses is difficult and time-consuming. So the team developed the HET Massive Galaxy Survey to winnow down the number of galaxies that would be interesting to study more closely.

“When trying to understand anything, you always look at the extremes: the most massive and the least massive,” Gebhardt said. “We chose a very large sample of the most massive galaxies in the nearby universe” to learn more about the relationship between black holes and their host galaxies.

Though still ongoing, the team has studied 700 of their 800 galaxies with HET. “This study is only possible with HET,” Gebhardt said. “The telescope works best when the galaxies are spread all across the sky. This is exactly what HET was designed for.”

The galaxy NGC 1277 (center) is embedded in the nearby Perseus galaxy cluster. All the ellipticals and round yellow galaxies in the picture are located in this cluster. NGC 1277 is a relatively compact galaxy compared to the galaxies around it. The Perseus cluster is 250 million light years from us. Credit: David W. Hogg, Michael Blanton, and the SDSS Collaboration

In the current paper, the team zeroes in on the top six most massive galaxies. They found that one of those, NGC 1277, had already been photographed by Hubble Space Telescope. This provided measurements of the galaxy’s brightness at different distances from its center. When combined with HET data and various models run via supercomputer, the result was a mass for the black hole of 17 billion suns (give or take 3 billion).

“The mass of this black hole is much higher than expected,” Gebhardt said. “It leads us to think that very massive galaxies have a different physical process in how their black holes grow.”

Reference: “An over-massive black hole in the compact lenticular galaxy NGC 1277” by Remco C. E. van den Bosch, Karl Gebhardt, Kayhan Gültekin, Glenn van de Ven, Arjen van der Wel and Jonelle L. Walsh, 28 November 2012, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/nature11592

Founded in 1932, The University of Texas at Austin’s McDonald Observatory hosts multiple telescopes undertaking a variety of astronomical research under the darkest night skies of any professional observatory in the continental United States. McDonald is home to one of the world’s largest telescopes, the 9.2-meter Hobby-Eberly Telescope, a joint project of The University of Texas at Austin, Pennsylvania State University, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, and Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. An international leader in astronomy education and outreach, the McDonald Observatory is also pioneering the next generation of astronomical research as a partner in the Giant Magellan Telescope.

Be the first to comment on "Massive Black Hole is 17 Billion Times Our Sun’s Mass"