A team of scientists from the University of Tokyo have identified a group of neurons in fruit fly brains responsible for visual aversion to perceived threats. The findings offer potential insights into how humans react to fear, and the team aims to further explore this brain circuitry, which may inform future treatments for anxiety disorders and phobias.

A cluster of neurons in the brains of fruit flies has been found to control visual aversion to scary objects.

Averting our eyes from things that scare us may be due to a specific cluster of neurons in a visual region of the brain, according to new research at the University of Tokyo. Researchers found that in fruit fly brains, these neurons release a chemical called tachykinin which appears to control the fly’s movement to avoid facing a potential threat. Fruit fly brains can offer a useful analogy for larger mammals, so this research may help us better understand our own human reactions to scary situations and phobias. Next, the team wants to find out how these neurons fit into the wider circuitry of the brain so they can ultimately map out how fear controls vision.

Do you cover your eyes during horror movies? Or perhaps the sight of a spider makes you turn and run? Avoiding looking at things that scare us is a common experience, for humans and animals. But what actually makes us avert our gaze from the things we fear? Researchers have found that it may be due to a group of neurons in the brain that regulates vision when feeling afraid.

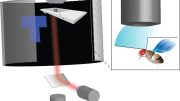

Calm flies wouldn’t show a change in behavior in response to a visual object, but fearful flies would run away from it. Credit: 2023, Tsuji et al.

“We discovered a neuronal mechanism by which fear regulates visual aversion in the brains of Drosophila (fruit flies). It appears that a single cluster of 20-30 neurons regulates vision when in a state of fear. Since fear affects vision across animal species, including humans, the mechanism we found may be active in humans as well,” explained Assistant Professor Masato Tsuji from the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Tokyo.

The team used puffs of air to simulate a physical threat and found that the flies’ walking speed increased after being puffed at. The flies also would choose a puff-free route if offered, showing that they perceived the puffs as a threat (or at least preferred to avoid them). Next, the researchers placed a small black object, roughly the size of a spider, 60 degrees to the right or left of the fly. On its own, the object didn’t cause a change in behavior, but when placed following puffs of air, the flies avoided looking at the object and moved so that it was positioned behind them.

To understand the molecular mechanism underlying this aversion behavior, the team then used mutated flies in which they altered the activity of certain neurons. While the mutated flies kept their visual and motor functions, and would still avoid the air puffs, they did not respond in the same fearful manner to visually avoid the object.

“This suggested that the cluster of neurons which releases the chemical tachykinin was necessary for activating visual aversion,” said Tsuji. “When monitoring the flies’ neuronal activity, we were surprised to find that it occurred through an oscillatory pattern, i.e., the activity went up and down similar to a wave. Neurons typically function by just increasing their activity levels, and reports of oscillating activity are particularly rare in fruit flies because up until recently the technology to detect this at such a small and fast scale didn’t exist.”

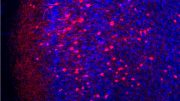

By giving the flies genetically encoded calcium indicators, the researchers could make the flies’ neurons shine brightly when activated. Thanks to the latest imaging techniques, they then saw the changing, wavelike pattern of light being emitted, which was previously averaged out and missed.

Next, the team wants to figure out how these neurons fit into the broader circuitry of the brain. Although the neurons exist in a known visual region of the brain, the researchers do not yet know from where the neurons are receiving inputs and to where they are transmitting them, to regulate visual escape from objects perceived as dangerous.

“Our next goal is to uncover how visual information is transmitted within the brain, so that we can ultimately draw a complete circuit diagram of how fear regulates vision,” said Tsuji. “One day, our discovery might perhaps provide a clue to help with the treatment of psychiatric disorders stemming from exaggerated fear, such as anxiety disorders and phobias.”

Reference: “Threat gates visual aversion via theta activity in Tachykinergic neurons” by Masato Tsuji, Yuto Nishizuka and Kazuo Emoto, 13 July 2023, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-39667-z

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through the Graduate Program for Leaders in Life Innovation (GPLLI), MEXT Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Dynamic regulation of brain function by Scrap and Build system” (KAKENHI 16H06456), JSPS (KAKENHI 16H02504), WPI-IRCN, AMED-CREST (JP21gm1310010), JST-CREST (JPMJCR22P6), Toray Foundation, Naito Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, and Uehara Memorial Foundation.

Be the first to comment on "Neurological Secrets of Fear: The Eye-Averting Mechanism Uncovered in Fruit Flies"