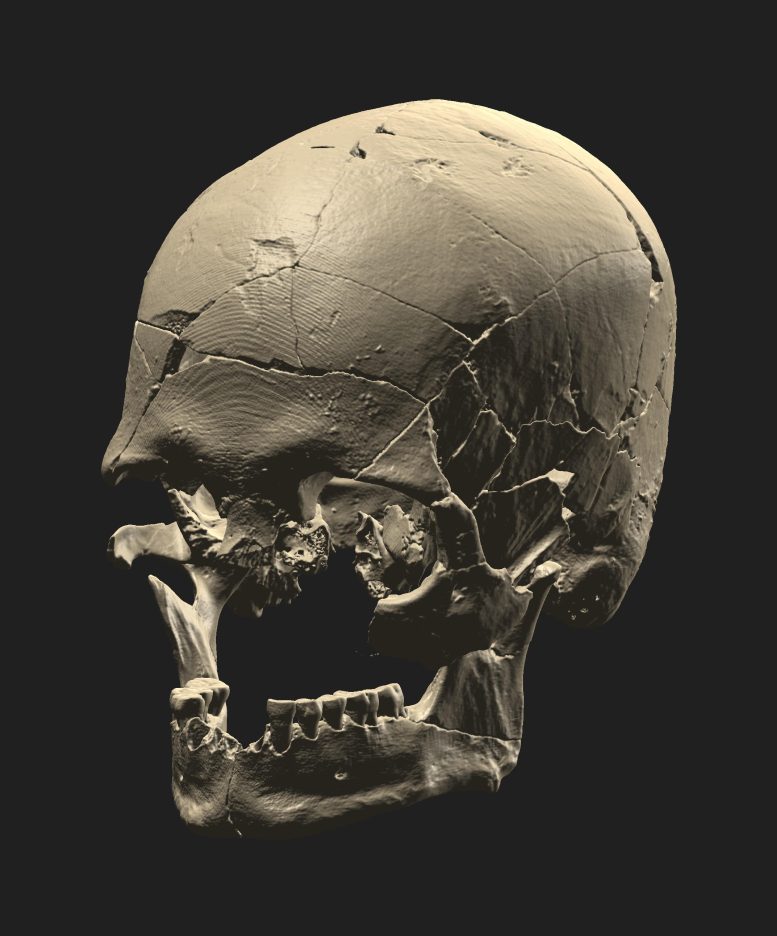

Three-dimensional renderization made from the tomography of Luzio’s cranium, an approximately 10,000 years fossil found in the Capelinha river midden in the Ribeira de Iguape valley. Cranial morphology is similar to that of Luzia, the oldest human fossil found to date in South America, reason why the researchers thought it might have belonged to a biologically different population from present-day Amerindians. The study published today refuted that hypothesis. Credit: André Strauss/MAE-USP

A study, conducted across four distinct regions of Brazil, performed genomic data analysis of 34 fossils, comprising larger skeletal remains as well as the renowned coastal mounds of shells and fishbones. This research revealed differences between communities.

A recent paper published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution presents evidence suggesting that Luzio, the most ancient human skeleton discovered in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, descended from the original population that established their home in the Americas over 16,000 years ago. This ancestral population is believed to have been the progenitors of all present-day Indigenous groups, such as the Tupi.

Relying on the most extensive collection of Brazilian archaeological genomic data to date, the study covered in the paper also proposes a reason for the vanishing of the earliest coastal communities. These communities are credited with constructing the renowned symbols of Brazilian archeology known as sambaquis — massive piles of shells and fishbones employed as homes, graveyards, and boundary markers. These monuments are often described by archeologists as shell mounds or kitchen middens.

“After the Andean civilizations, the Atlantic coast sambaqui builders were the human phenomenon with the highest demographic density in pre-colonial South America. They were the ‘kings of the coast’ for thousands and thousands of years. They vanished suddenly about 2,000 years ago,” said André Menezes Strauss, an archeologist at the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Archeology and Ethnology (MAE-USP) and principal investigator for the study.

The first author of the article is Tiago Ferraz. The study was supported by FAPESP (projects 17/16451-2 and 20/06527-4) and conducted in partnership with researchers at the University of Tübingen’s Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment (Germany).

The authors analyzed the genomes of 34 samples from four different areas of Brazil’s coast. The fossils were at least 10,000 years old. They came from sambaquis and other parts of eight sites (Cabeçuda, Capelinha, Cubatão, Limão, Jabuticabeira II, Palmeiras Xingu, Pedra do Alexandre, and Vau Una).

This material included Luzio, São Paulo’s oldest skeleton, found in the Capelinha river midden in the Ribeira de Iguape valley by a group led by Levy Figuti, a professor at MAE-USP. The morphology of its skull is similar to that of Luzia, the oldest human fossil found to date in South America, dating from about 13,000 years ago. The researchers thought it might have belonged to a biologically different population from present-day Amerindians, who settled in what is now Brazil some 14,000 years ago, but it turns out they were mistaken.

“Genetic analysis showed Luzio to be an Amerindian, like the Tupi, Quechua, or Cherokee. That doesn’t mean they’re all the same, but from a global perspective, they all derive from a single migratory wave that arrived in the Americas not more than 16,000 years ago. If there was another population here 30,000 years ago, it didn’t leave descendants among these groups,” Strauss said.

Luzio’s DNA also answered another question. River middens are different from coastal ones, so the find cannot be considered a direct ancestor of the huge classical sambaquis that appeared later. This discovery suggests there were two distinct migrations – into the hinterland and along the coast.

What happened to the sambaqui builders?

Analysis of the genetic material revealed heterogeneous communities with cultural similarities but significant biological differences, especially between coastal communities in the southeast and south.

“Studies of cranial morphology conducted in the 2000s had already pointed to a subtle difference between these communities, and our genetic analysis confirmed it,” Strauss said. “We discovered that one of the reasons was that these coastal populations weren’t isolated but ‘swapped genes’ with inland communities. Over thousands of years, this process must have contributed to the regional differences between sambaquis.”

Regarding the mysterious disappearance of this coastal civilization, comprising the first hunter-gatherers of the Holocene, analysis of the DNA samples clearly showed that, in contrast with the European Neolithic substitution of entire populations, what happened in this part of the world was a change of practices, with a decline in construction of shell middens and the introduction of pottery by sambaqui builders. For example, the genetic material found at Galheta IV (Santa Catarina state), the most emblematic site for the period, has remains not of shells but of ceramics and is similar to the classic sambaquis in this respect.

“This information is compatible with a 2014 study that analyzed pottery shards from sambaquis and found that the pots in question were used to cook not domesticated vegetables but fish. They appropriated technology from the hinterland to process food that was already traditional there,” Strauss said.

Reference: “Genomic history of coastal societies from eastern South America” by Tiago Ferraz, Ximena Suarez Villagran, Kathrin Nägele, Rita Radzevičiūtė, Renan Barbosa Lemes, Domingo C. Salazar-García, Verônica Wesolowski, Marcony Lopes Alves, Murilo Bastos, Anne Rapp Py-Daniel, Helena Pinto Lima, Jéssica Mendes Cardoso, Renata Estevam, Andersen Liryo, Geovan M. Guimarães, Levy Figuti, Sabine Eggers, Cláudia R. Plens, Dionne Miranda Azevedo Erler, Henrique Antônio Valadares Costa, Igor da Silva Erler, Edward Koole, Gilmar Henriques, Ana Solari, Gabriela Martin, Sérgio Francisco Serafim Monteiro da Silva, Renato Kipnis, Letícia Morgana Müller, Mariane Ferreira, Janine Carvalho Resende, Eliane Chim, Carlos Augusto da Silva, Ana Claudia Borella, Tiago Tomé, Lisiane Müller Plumm Gomes, Diego Barros Fonseca, Cassia Santos da Rosa, João Darcy de Moura Saldanha, Lúcio Costa Leite, Claudia M. S. Cunha, Sibeli Aparecida Viana, Fernando Ozorio Almeida, Daniela Klokler, Henry Luydy Abraham Fernandes, Sahra Talamo, Paulo DeBlasis, Sheila Mendonça de Souza, Claide de Paula Moraes, Rodrigo Elias Oliveira, Tábita Hünemeier, André Strauss and Cosimo Posth, 31 July 2023, Nature Ecology & Evolution.

DOI: 10.1038/s41559-023-02114-9

The study was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation.

Be the first to comment on "São Paulo’s 10,000-Year-Old Skeleton Proves To Be Amerindian"