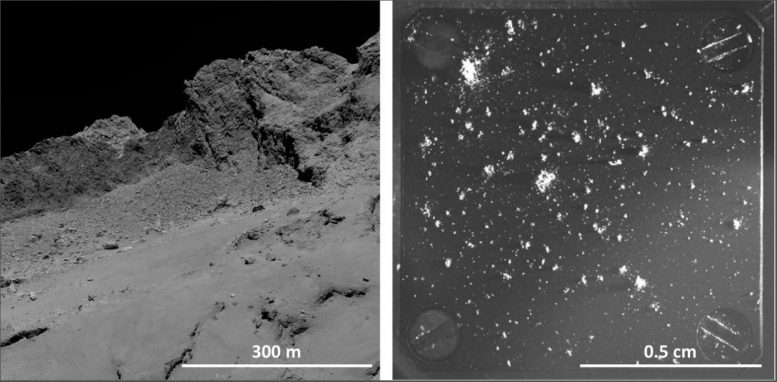

Glimpse of an alien world: As comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko approaches the Sun, frozen gases evaporate from below the surface, dragging tiny particles of dust along with them (left). These dust grains can be captured and examined using the COSIMA instrument. Targets such as this one measuring only a few centimeters act as dust collectors. They retain dust particles of up to 100 microns in size (right). ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team

The dust that comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko emits into space consists of about one-half of organic molecules. The dust also belongs to the most pristine and carbon-rich material known in our solar system; it has hardly changed since its birth. These are the results of the COSIMA team, an instrument onboard the Rosetta spacecraft, which investigated the comet. In their current study, the involved researchers including scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research analyze as comprehensively as never before, what chemical elements constitute cometary dust.

When a comet traveling along its highly elliptical orbit approaches the Sun, it becomes active: frozen gases evaporate, dragging tiny dust grains into space. Capturing and examining these grains provides the opportunity to trace the “building materials” of the comet itself. So far, only a few space missions have succeeded in this endeavor. These include ESA’s Rosetta mission. Unlike their predecessors, for their current study the Rosetta researchers were able to collect and analyze dust particles of various sizes over a period of approximately two years. In comparison, earlier missions, such as Giotto’s Flyby of comet 1P/Halley or Stardust, which even returned cometary dust from comet 81P/Wild 2 back to Earth, provided only a snapshot. In the case of the space probe Stardust, which raced past its comet in 2004, the dust had changed significantly during capture, so a quantitative analysis was only possible to a limited extent.

In the course of the Rosetta mission, COSIMA collected more than 35000 dust grains. The smallest of them measured only 0.01 millimeters in diameter, the largest about one millimeter. The instrument makes it possible to first observe the individual dust grains with a microscope. In a second step, these grains are bombarded with a high-energy beam of indium ions. The secondary ions emitted in this way can then be “weighed” and analyzed in the COSIMA mass spectrometer. For the current study, the researchers limited themselves to 30 dust grains with properties that ensured a meaningful analysis. Their selection includes dust grains from all phases of the Rosetta mission and of all sizes.

“Our analyzes show that the composition of all these grains is very similar,” MPS researcher Dr. Martin Hilchenbach, Principal Investigator of the COSIMA team, describes the results. The scientists conclude that the comet’s dust consists of the same “ingredients” as the comet’s nucleus and thus can be examined in its place.

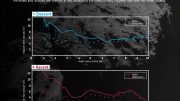

As the study shows, organic molecules are among those ingredients at the top of the list. These account for about 45 percent of the weight of the solid cometary material. “Rosetta’s comet thus belongs to the most carbon-rich bodies we know in the solar system,” says MPS scientist and COSIMA team member Dr. Oliver Stenzel. The other part of the total weight, about 55 percent, is provided by mineral substances, mainly silicates. It is striking that they are almost exclusively non-hydrated minerals i.e. missing water compounds.

“Of course, Rosetta’s comet contains water like any other comet, too,” says Hilchenbach. “But because comets have spent most of their time at the icy rim of the solar system, it has almost always been frozen and could not react with the minerals.” The researchers therefore regard the lack of hydrated minerals in the comet’s dust as an indication that 67P contains very pristine material.

This conclusion is supported by the ratio of certain elements such as carbon to silicon. With more than 5, this value is very close to the Sun’s value, which is thought to reflect the ratio found in the early solar system.

The current findings also touch on our ideas of how life on Earth came about. In a previous publication, the COSIMA team was able to show that the carbon found in Rosetta’s comet is mainly in the form of large, organic macromolecules. Together with the current study, it becomes clear that these compounds make up a large part of the cometary material. Thus, if comets indeed supplied the early Earth with organic matter, as many researchers assume, it would probably have been in majority in the form of such macromolecules.

The Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research heads the COSIMA team. The instrument was developed and built by a consortium led by the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. Other members of the consortium are the Laboratoire de Physique et Chimie de l’Environnement, the Institut d’Astrophysique, the Finnish Meteorological Institute, the University of Wuppertal, the Universität der Bundeswehr, the Research Center Seibersdorf and the Institute for Space Research at the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Reference: “Carbon-rich dust in comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko measured by COSIMA/Rosetta” by Anaïs Bardyn, Donia Baklouti, Hervé Cottin, Nicolas Fray, Christelle Briois, John Paquette, Oliver Stenzel, Cécile Engrand, Henning Fischer, Klaus Hornung, Robin Isnard, Yves Langevin, Harry Lehto, Léna Le Roy, Nicolas Ligier, Sihane Merouane, Paola Modica, François-Régis Orthous-Daunay, Jouni Rynö, Rita Schulz, Johan Silén, Laurent Thirkell, Kurt Varmuza, Boris Zaprudin, Jochen Kissel and Martin Hilchenbach, 28 November 2017, MNRAS.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stx2640

Be the first to comment on "Scientists Analyze the Chemical Elements That Make Up Comet 67P"