With a surge in cocaine use and related fatalities in the US, researchers at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute are studying the disorder, focusing on the theory of reinforcer pathology. They’re using a monetary incentive approach for drug-free behavior, seeking to develop innovative interventions to curb the rising issue.

Virginia Tech researcher at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute hope the study will inform demand and cravings for a substance involved in nearly one in five overdose deaths.

Nearly 2 percent of the U.S. population reported cocaine use in 2020, and the highly addictive substance was involved in nearly one in five overdose deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

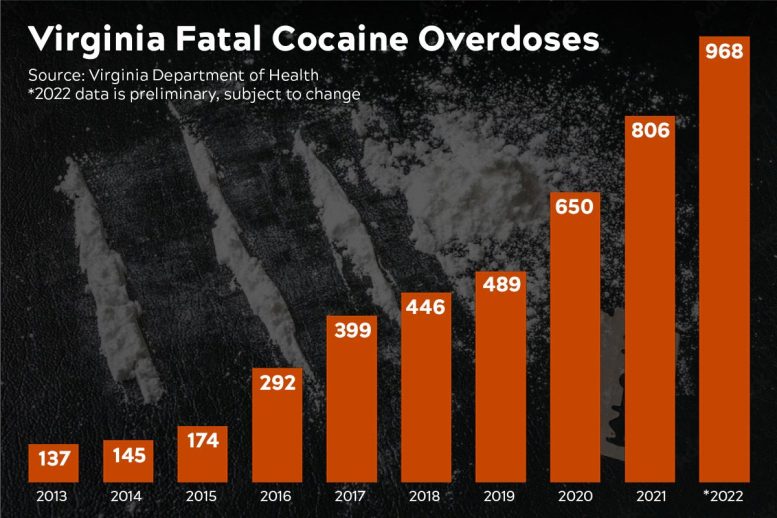

In Virginia, the number of cocaine-related overdoses has been increasing since 2013, with 968 fatal overdoses in 2022, a 20 percent increase over 2021, according to preliminary data from the Virginia Department of Health. Of those, four in five included fentanyl — prescription, illicit, or analog — a driving force behind the fatalities.

Researchers at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC are working to better understand cocaine use disorder and help reverse the national trend.

“Stimulants are coming back. Cocaine use and addiction has been rising for more than a decade with no robust treatment,” said Warren Bickel, professor with the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC and director of the Addiction Recovery Research Center. “We need some new ideas.”

The total number of fatal cocaine-related overdoses in Virginia has been slowly increasing since 2013. Researchers at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC are working to better understand cocaine use disorder to help reverse the trend. Credit: Leigh Anne Kelley/Virginia Tech

The study stresses the theory of reinforcer pathology, in which an individual places a higher value on immediate reward — for instance, for the way a substance makes them feel — and a lower value on future gains. For the study, researchers will use cocaine contingency management by providing cash or something of value to people who meet their treatment goals.

“When people do drugs, we know they give up their jobs, relationships, family, even their lives, but when they receive several dollars for drug-free urine samples, they become powerful. What explains that? Their temporal horizon. I give you money for a clean urine sample and right away you turn it around. The drugs lose value,” Bickel said.

The Addiction Recovery Research Center is recruiting adults who use cocaine for the paid research study on decision-making. Participants will be asked to visit the Roanoke lab 13 times over five weeks to undergo MRIs, report their cocaine use, take computerized assessments, and provide urine samples. The research, which is not a treatment study, is supported by a grant of more than $700,000 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the National Institutes of Health.

“We are asking people to participate for several weeks in a row, and we will learn whether tackling their short-term view of the future can be an added key to treating them,” Bickel said. “It is worthwhile to explore new ideas. New interventions are long overdue, and there is increasing evidence that this effort is an idea whose time has arrived. It is producing effects we want to measure.”

Bickel also is director of the institute’s Center for Health Behaviors Research, a psychology professor with Virginia Tech’s College of Science, and a professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. He is joined on the study by co-investigator Stephen M. LaConte, an associate professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute.

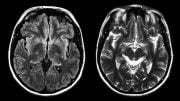

LaConte said he’s privileged to work alongside colleagues tackling substance use disorders. “I am thankful to the participants who donate their time to come to the [institute] for our studies,” said LaConte, who will use brain imaging to study the effects of cocaine use and changes to the brain during the intervention. “Beyond funding the science that we do here, I am also grateful to our state and federal agencies for their work in helping to reduce the stigma surrounding addiction.”

Their goal is to positively impact public health by guiding innovative interventions that help decrease cocaine consumption.

Funding: NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse

Cocaine is not addictive.

This is fake science. The “highly addictive substance” cocaine is not in fact medically or scientifically

addictive. There is no physical dependence to cocaine. The word “addiction” is often casually used in relation to anything people like a lot, but there is no science here. There is, of course, an addiction to government grant money to support fake science.