The launch of Apollo 16 on April 16, 1972, marked the beginning of the fifth Moon landing mission.

The fifth Moon landing mission began with the April 16, 1972 launch of Apollo 16. The giant Saturn V rocket lifted off from Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida with Commander John W. Young, Command Module Pilot Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly, and Lunar Module Pilot Charles M. Duke strapped inside their capsule.

The Apollo 16 crew of Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly, left, John W. Young, and Charles M. Duke. Credit: NASA

After their rocket delivered them into a parking orbit around the Earth, the third stage reignited to send them on their way to the Moon. Following an uneventful three-day coast to the Moon, Young, Mattingly, and Duke arrived in lunar orbit on April 19 to prepare for the landing in and exploration of the Descartes site and to conduct scientific observations from lunar orbit.

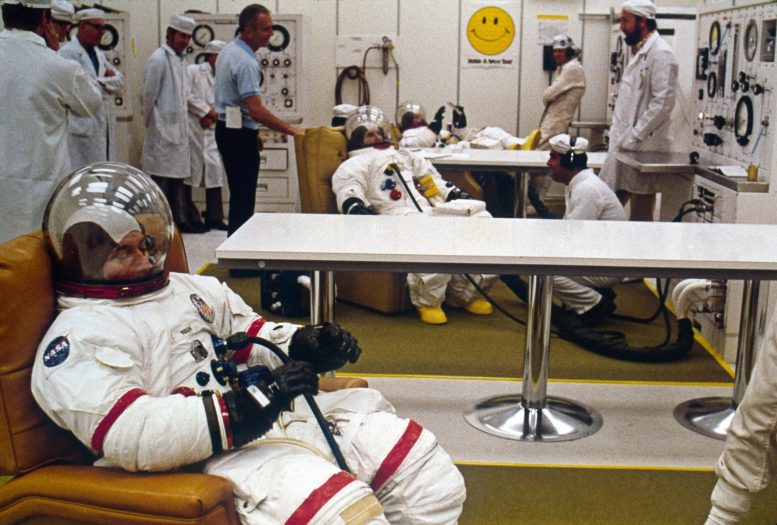

The terminal countdown for Apollo 16’s launch began on April 14 and proceeded without any significant issues. Engineers in Firing Room 1 of KSC’s Launch Control Center (LCC) monitored all aspects of the countdown, including the final fueling of the Saturn V rocket. Young, Mattingly, and Duke ate their traditional steak and eggs breakfast before putting on their spacesuits and taking the Astrovan to Launch Pad 39A, where they boarded their spacecraft, the Command Module (CM) Casper.

At the traditional prelaunch breakfast, Apollo 16 astronauts John W. Young, Thomas K. Mattingly, and Charles M. Duke are joined by backup and support astronauts and managers. Credit: NASA

Young took the left-hand seat, Duke the right, and finally Mattingly settled in the middle. Thousands of spectators assembled along the beaches near KSC to view the launch. Vice President Spiro T. Agnew arrived in the firing room’s viewing gallery to watch the launch with senior NASA managers.

Apollo 16 astronauts Young, left, Mattingly, and Duke suiting up prior to their launch. Credit: NASA

The countdown continued smoothly, with perfect weather for the launch. Liftoff on 7.7 million pounds (3.5 million kilograms) of thrust came at 12:54 p.m. Eastern on April 16, 1972. The Saturn V rocket launched Apollo 16 into a clear afternoon sky. Ten seconds after the first motion, the rocket cleared the launch tower and mission responsibility shifted from KSC’s Firing Room 1 to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

In Firing Room 1 of the Launch Control Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, engineers monitor the progress of the Apollo 16 countdown. Credit: NASA

In the MCC, Flight Director Eugene F. Kranz led his White Team of controllers who monitored this phase of the mission, with NASA astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton acting as capsule communicator (capcom), the person who talked directly to the crew during the flight. After burning for 2 minutes and 42 seconds and lifting the rocket to an altitude of 40 miles (64 kilometers), the first stage engines shutoff and the stage jettisoned.

In the Firing Room 1 viewing gallery, NASA Deputy Administrator George M. Low, left,

NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher, and Vice President Spiro T.

Agnew observe the Apollo 16 launch. Credit: NASA

The second stage continued to power the ascent until 9 minutes 20 seconds, taking the spacecraft nearly to orbit, at which time it too was jettisoned, and the third stage took over. It burned for two and a half minutes to place Apollo 16 into a circular 105-mile-high (169-kilometer-high) parking orbit around the Earth. The astronauts were now weightless, and Young reported enthusiastically, “Boy, it’s just beautiful up here, looking out the window. It’s just really fantastic. And the thing worked like a gem.”

For the next two and a half hours, Apollo 16, still attached to the Saturn V’s third stage, orbited the Earth. Young, Mattingly, and Duke removed their helmets and gloves but for now kept their spacesuits on. Together with Mission Control, they determined that all onboard systems were working nominally and that they could proceed with Trans-Lunar Injection (TLI), the second burn of the Saturn V’s third stage, to send them out of Earth orbit and toward the Moon. The engine ignited and fired for 5 minutes and 51 seconds, increasing Apollo 16’s velocity to 24,229 miles per hour (38,992 kph) to begin the three-day coast to the Moon.

The Apollo 16 astronauts took this photograph of Baja California, Mexico, during the first revolution around the Earth. Credit: NASA

Twenty-five minutes after the shutdown of the third stage engine, Fullerton called up to the crew that they were “Go” for the transposition and docking maneuver. Six minutes later, and already more than 4,200 miles (6,800 kilometers) from Earth, Mattingly separated the Command and Service Module Casper from the spent stage that still held the Lunar Module (LM) Orion. He moved Casper about 60 feet away before turning it around and starting the rendezvous process.

Duke set up a camera in the window and Mission Control received the image of the LM as they slowly approached it, along with what Duke called “a zillion particles” traveling with them, most likely flakes of paint from the LM. Seventeen minutes later, Mattingly brought the two spacecraft together to achieve a soft docking. Latches then joined the two to complete a hard docking. By the conclusion of the docking maneuver, less than three and a half hours after liftoff, Apollo 16 had traveled more than 7,800 miles (12,600 kilometers) from Earth.

The Apollo 16 Lunar Module Orion still attached to the Saturn V rocket’s third stage during the transposition and docking maneuver. Credit: NASA

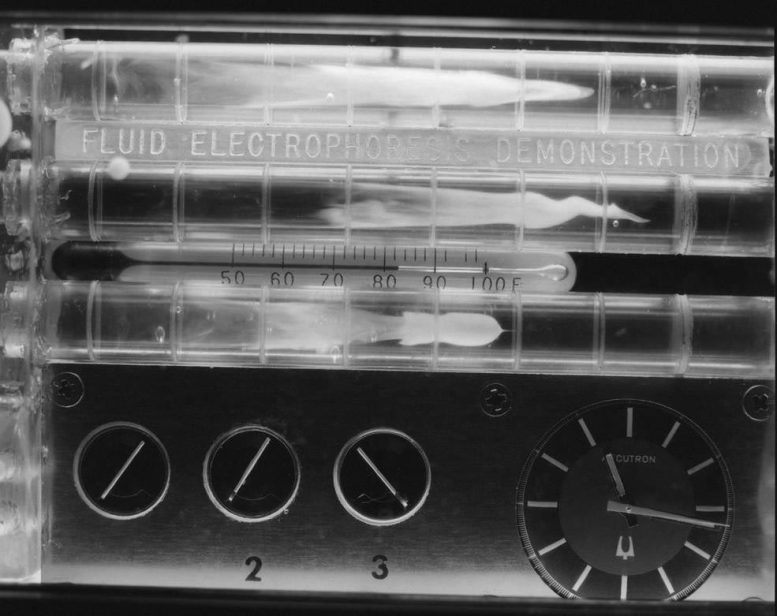

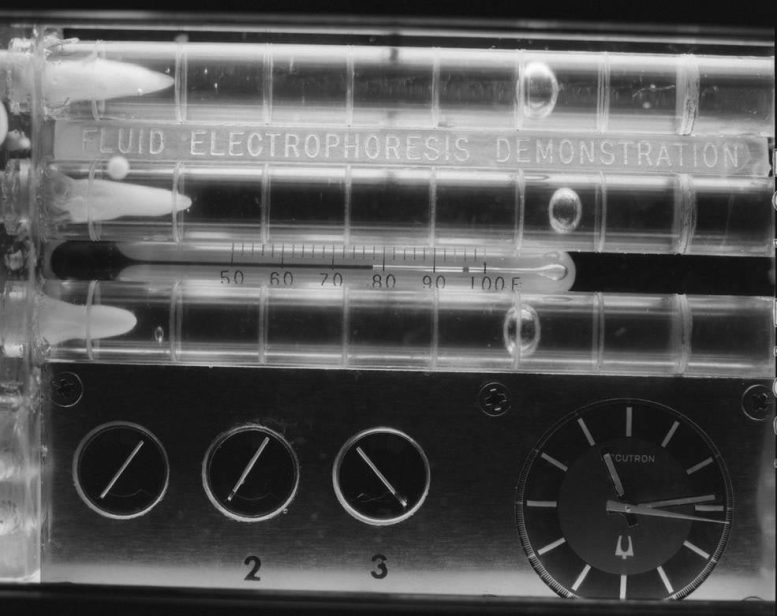

While the crew slept, in Mission Control Flight Director Kranz and his White Team of controllers resumed their positions at the consoles, with astronaut Anthony W. “Tony” England as the new capcom. After a quiet night, the crew woke up, now 113,000 miles (182,000 kilometers) from Earth. The first activity of the day involved activating the Fluid Electrophoresis Demonstration experiment to assess the feasibility of using electrophoresis in space to separate cells and large molecules. Later in the day, Frank’s Orange Team of controllers with Peterson as capcom resumed their consoles to help the astronauts conduct a midcourse correction (MCC-2) maneuver, a two-second burn of the 20,000-pound (9,100-kilograms) thrust Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine to lower the point of closest approach to the Moon from 135 miles (217 kilometers) to 82 miles (132 kilometers), the correct altitude for the Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI) burn. Young and Duke activated the LM Orion, spending about two hours activating and checking out its systems and transferring items such as film cassettes. Mattingly made a brief visit inside Orion to take a peek. Philip C. Shaffer, a flight director assigned to the Skylab program, began his first shift, as he and his Purple Team came on for the overnight shift, with Hartsfield once again as capcom. Young, Mattingly, and Duke went to sleep, now 162,000 miles (261,000 kilometers) from Earth.

Successive views of the receding Earth as Apollo 16 makes its way to the Moon. Credit: NASA

The astronauts began their third day in space already 176,000 miles (283,000 kilometers) from Earth. One of the experiments on this day sought to gain more information about the light flashes seen by many Moon-bound astronauts. Young, Duke, and Mattingly all donned the helmet and face shield of the Apollo Light Flash Moving Emulsion Detector experiment and reported to Mission Control on the type, frequency, and color of any light flashed they saw. Flight Director Shaffer decided that they could skip the planned third MCC as their trajectory continued to be highly precise. Young and Duke once again activated Orion and in a rehearsal of procedures used on landing day, they donned their spacesuits, without helmets and gloves, and the practiced transferring through the docking tunnel. During their dinner, all three astronauts tested foods and packaging planned for the Skylab program, such as snap-top cans, packets of salt, packages with spoonable foods, and plastic bellows beverage containers. Shortly before the astronauts went to sleep, they crossed the invisible boundary that marked the transition between the Earth’s and the Moon’s gravitational sphere of influence, and Apollo 16 began to accelerate toward its target. As the crew fell asleep, only 38,700 miles (62,300 kilometers) separated them from the Moon.

Two sequential photographs of the Fluid Electrophoresis Demonstration experiment carried out during Apollo 16, showing the differential movement of particles from left to right. Credit: NASA

By the time Young, Mattingly, and Duke awoke to begin their fourth day in space, they had closed the distance to the Moon to just 22,200 miles (35,700 kilometers). Once again, Mission Control canceled a planned midcourse correction maneuver as the spacecraft continued to maintain a steady trajectory. The astronauts jettisoned the panel that covered the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay in the Service Module. During launch and the translunar coast, the 5-by-9-foot (1.5-by-2.7-meter) panel, sometimes referred to as the world’s largest lens cap, protected the cameras and other instruments and a deployable subsatellite in the SIM-bay used to study the Moon and its environment from orbit.

Several hours later, as previous lunar missions had done, Apollo 16 disappeared behind the leading edge of the Moon and communications with Mission Control stopped as expected. While behind the Moon, precisely 74 hours and 28 minutes after leaving Earth, Apollo 16 fired its SPS engine for 6 minutes and 14 seconds to enter an elliptical orbit around the Moon.

To be continued…

Be the first to comment on "50 Years Ago: NASA Apollo 16 Launches to the Moon"