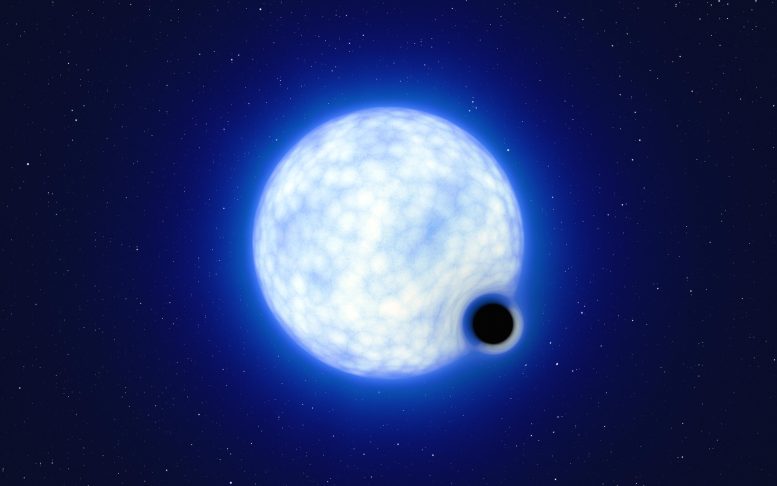

VFTS 243 is a binary system of a large, hot blue star and a black hole orbiting each other, as seen in this animation. Credit: ESO/L.Calçada

Discovery Sheds Light on Star Death, Black Hole Formation and Gravitational Waves

When it comes to field of black hole research, it seems there is always something new and exciting happening.

In 1922, Albert Einstein first published his book explaining the theory of general relativity – which postulated black holes. Now, one hundred years later, astronomers captured actual images of the black hole at the center of the Milky Way. In a recent paper, a team of astronomers describes another exciting new discovery: the first “dormant” black hole observed outside of the galaxy.

I am an astrophysicist who has studied black holes – the most dense objects in the universe – for nearly two decades. Black holes that do not emit any detectable light are known as dormant black holes. They are notoriously difficult to find. This new discovery is especially exciting because it provides insight into the formation and evolution of black holes. This information is essential for understanding gravitational waves as well as other astronomical events.

What exactly is VFTS 243?

VFTS 243 is a binary system, which means it is composed of two objects that orbit a common center of mass. The first object is a very hot, blue star with 25 times the mass of the Sun, and the second is a black hole nine times more massive than the Sun. VFTS 243 is located in the Tarantula Nebula within the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way located about 163,000 light-years from Earth.

This video begins with a view of the Milky Way and zooms all the way to VFTS 243, which is located in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

The black hole in VFTS 243 is considered dormant because it is not emitting any detectable radiation. This is in stark contrast to other binary systems in which strong X-rays are detected from the black hole.

The black hole has a diameter of around 33 miles (54 kilometers) and is dwarfed by the energetic star, which is some 200,000 times larger. Both rapidly rotate around a common center of mass. Even with the most powerful telescopes, the system visually appears to be a single blue dot.

Finding dormant black holes

Astronomers suspect there are hundreds of such binary systems with black holes that do not emit X-rays hiding in the Milky Way and the Large Magellanic Cloud. Black holes are most easily visible when they are stripping matter from a companion star, a process known as “feeding.”

Feeding produces a disk of gas and dust that surrounds the black hole. When the material in the disk falls inward toward the black hole, friction heats the accretion disk to millions of degrees. These hot disks of matter emit a tremendous amount of X-rays. The first black hole to be detected in this manner is the famed Cygnus X-1 system.

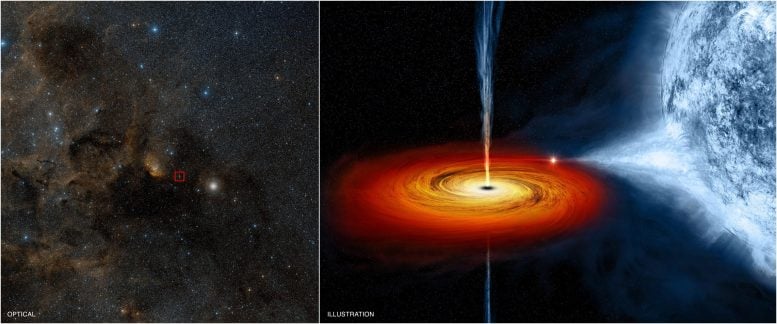

On the left is an optical image showing Cygnus X-1 outlined by a red box. On the right is an artist rendition showing the outer layers of the black hole siphoning off matter from the companion star and forming an accretion disk. Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC; Optical: Digitized Sky Survey

For years astronomers have known that VFTS 243 is a binary system, but whether the system is a pair of stars or a dance between a single star and a black hole was unclear. To determine which was true, the research team studying the binary used a technique called spectral disentangling. This technique separates the light from VFTS 243 into its constituent wavelengths, which is similar to what happens when white light enters a prism and the different colors are produced.

This analysis revealed that the light from VFTS 243 was from a single source, not two separate stars. With no detectable radiation emanating from the star’s companion, the only possible conclusion was that the second body within the binary is a black hole and thus the first dormant black hole found outside of the Milky Way galaxy.

This artist’s impression shows what the binary system VFTS 243 might look like if we were observing it up close. The system, which is located in the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud, is composed of a hot, blue star with 25 times the Sun’s mass and a black hole, which is at least nine times the mass of the Sun. The sizes of the two binary components are not to scale: in reality, the blue star is about 200,000 times larger than the black hole. Note that the ‘lensing’ effect around the black hole is shown for illustration purposes only, to make this dark object more noticeable in the image. The inclination of the system means that, when looking at it from Earth, we cannot observe the black hole eclipsing the star. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

Why is VFTS 243 important?

Most black holes with a mass of less than 100 Suns are formed from the collapse of a massive star. When this happens, often there is a tremendous explosion known as a supernova.

The fact that the black hole in VFTS 243 system is in a circular orbit with the star is strong evidence that there was no supernova explosion, which otherwise might have kicked the black hole out of the system – or at the very least disrupted the orbit. Instead, it appears that the progenitor star collapsed directly to form the black hole sans explosion.

The massive star in the VFTS 243 system will live for only another 5 million years – a blink of an eye in astronomical timescales. The death of the star should result in the formation of another black hole, transforming the VFTS 243 system into a black hole binary.

To date, astronomers have detected nearly 100 events where binary black holes merge and produced ripples in space-time. But how these binary black hole systems form is still unknown, which is why VFTS 243 and similar yet-to-be-discovered systems are so vital to future research. Perhaps nature has a sense of humor – for black holes are the darkest objects in existence and emit no light, yet they illuminate our fundamental understanding of the universe.

Written by Idan Ginsburg, Academic Faculty in Physics & Astronomy, Georgia State University.

This article was first published in The Conversation.![]()

For more on this research, see “Black Hole Police” Discover Needle in a Haystack.

Reference “An X-ray quiet black hole born with a negligible kick in a massive binary of the Large Magellanic Cloud” by Tomer Shenar, Hugues Sana, Laurent Mahy, Kareem El-Badry, Pablo Marchant, Norbert Langer, Calum Hawcroft, Matthias Fabry, Koushik Sen, Leonardo A. Almeida, Michael Abdul-Masih, Julia Bodensteiner, Paul A. Crowther, Mark Gieles, Mariusz Gromadzki, Vincent Hénault-Brunet, Artemio Herrero, Alex de Koter, Patryk Iwanek, Szymon Kozłowski, Daniel J. Lennon, Jesús Maíz Apellániz, Przemysław Mróz, Anthony F. J. Moffat, Annachiara Picco, Paweł Pietrukowicz, Radosław Poleski, Krzysztof Rybicki, Fabian R. N. Schneider, Dorota M. Skowron, Jan Skowron, Igor Soszyński, Michał K. Szymański, Silvia Toonen, Andrzej Udalski, Krzysztof Ulaczyk, Jorick S. Vink and Marcin Wrona, 18 July 2022, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-022-01730-y

Be the first to comment on "Astronomers Have Discovered an Especially Sneaky Black Hole"