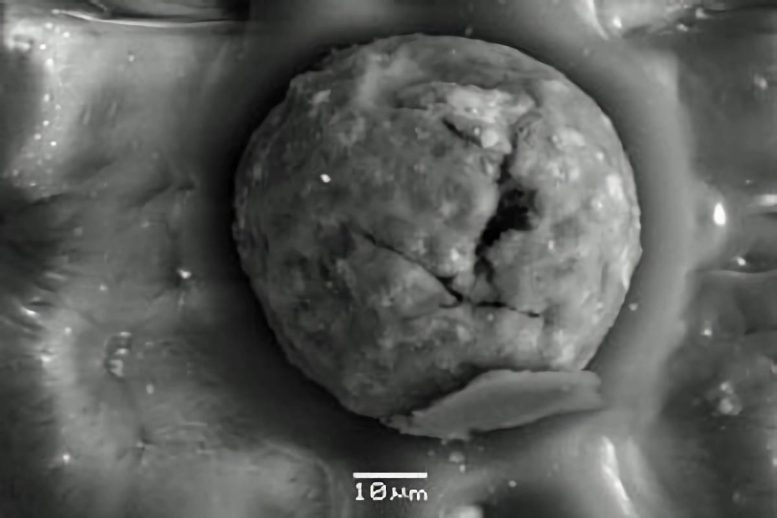

An environmental scanning electron microscope image of a carbon spherule from Sheriden Cave. Credit: University of Cincinnati

A newly published study reveals evidence of a major cosmic event near the end of the Ice Age, detailing how a cosmic impact sparked climate change that caused mass extinctions.

Herds of wooly mammoths once shook the earth beneath their feet, sending humans scurrying across the landscape of prehistoric Ohio. But then something much larger shook the Earth itself, and at that point these mega mammals’ days were numbered.

Something – global-scale combustion caused by a comet scraping our planet’s atmosphere or a meteorite slamming into its surface – scorched the air, melted bedrock, and altered the course of Earth’s history. Exactly what it was is unclear, but this event jump-started what Kenneth Tankersley, an assistant professor of anthropology and geology at the University of Cincinnati, calls the last gasp of the last ice age.

“Imagine living in a time when you look outside and there are elephants walking around in Cincinnati,” Tankersley says. “But by the time you’re at the end of your years, there are no more elephants. It happens within your lifetime.”

Tankersley explains what he and a team of international researchers found may have caused this catastrophic event in Earth’s history in their research, “Evidence for Deposition of 10 Million Tonnes of Impact Spherules Across Four Continents 12,800 Years Ago,” which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The prestigious journal was established in 1914 and publishes innovative research reports from a broad range of scientific disciplines. Tankersley’s research also was included in the History Channel series “The Universe: When Space Changed History” and will be featured in an upcoming film for The Weather Channel.

This research might indicate that it wasn’t the cosmic collision that extinguished the mammoths and other species, Tankersley says, but the drastic change to their environment.

“The climate changed rapidly and profoundly. And coinciding with this very rapid global climate change was mass extinctions.”

Putting a Finger on the End of the Ice Age

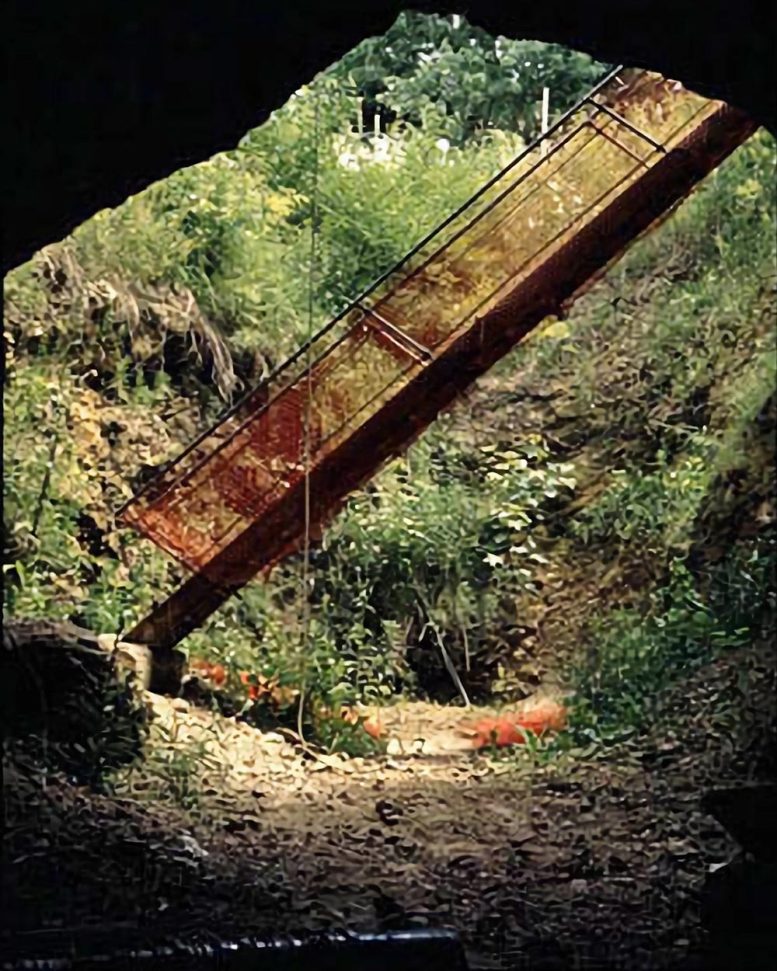

Tankersley is an archaeological geologist. He uses geological techniques, in the field and laboratory, to solve archaeological questions. He’s found a treasure trove of answers to some of those questions in Sheriden Cave in Wyandot County, Ohio. It’s in that spot, 100 feet (30 meters) below the surface, where Tankersley has been studying geological layers that date to the Younger Dryas time period, about 13,000 years ago.

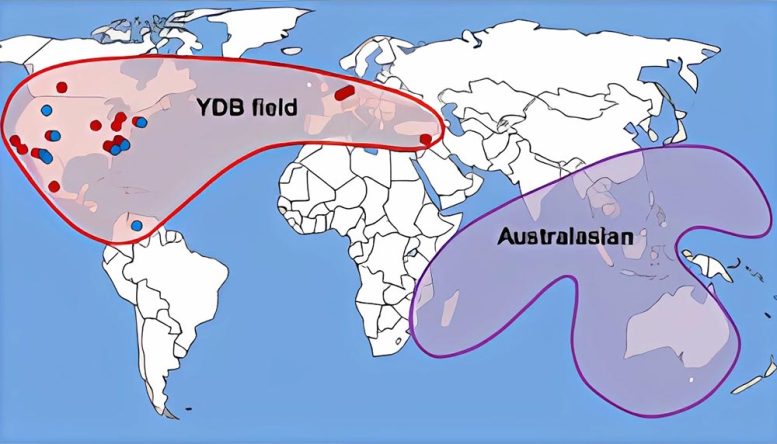

The Younger Dryas Boundary strewnfield shown (red) with YDB sites as red dots and those by eight independent groups as blue dots. Also shown is the largest known impact strewnfield, the Australasian (purple). Credit: University of Cincinnati

About 12,000 years before the Younger Dryas, the Earth was at the Last Glacial Maximum – the peak of the Ice Age. Millennia passed, and the climate began to warm. Then something happened that caused temperatures to suddenly reverse course, bringing about a century’s worth of near-glacial climate that marked the start of the geologically brief Younger Dryas.

There are only about 20 archaeological sites in the world that date to this time period and only 12 in the United States – including Sheriden Cave.

“There aren’t many places on the planet where you can actually put your finger on the end of the last ice age, and Sheriden Cave is one of those rare places where you can do that,” Tankersley says.

Rock-Solid Evidence of Cosmic Calamity

In studying this layer, Tankersley found ample evidence to support the theory that something came close enough to Earth to melt rock and produce other interesting geological phenomena. Foremost among the findings were carbon spherules. These tiny bits of carbon are formed when substances are burned at very high temperatures. The spherules exhibit characteristics that indicate their origin, whether that’s from burning coal, lightning strikes, forest fires, or something more extreme. Tankersley says the ones in his study could only have been formed from the combustion of rock.

The University of Cincinnati’s Ken Tankersley used excavations at Sheriden Cave in Wyandot, Ohio, in his research on the Younger Dryas. Credit: Provided by Ken Tankersley, University of Cincinnati

The spherules also were found at 17 other sites across four continents – an estimated 10 million metric tons’ worth – further supporting the idea that whatever changed Earth did so on a massive scale. It’s unlikely that a wildfire or thunderstorm would leave a geological calling card that immense – covering about 50 million square kilometers (19 million square miles).

“We know something came close enough to Earth and it was hot enough that it melted rock – that’s what these carbon spherules are. In order to create this type of evidence that we see around the world, it was big,” Tankersley says, contrasting the effects of an event so massive with the 1883 volcanic explosion on Krakatoa in Indonesia. “When Krakatoa blew its stack, Cincinnati had no summer. Imagine winter all year round. That’s just one little volcano blowing its top.”

Other important findings include:

- Micrometeorites: smaller pieces of meteorites or particles of cosmic dust that have made contact with the Earth’s surface.

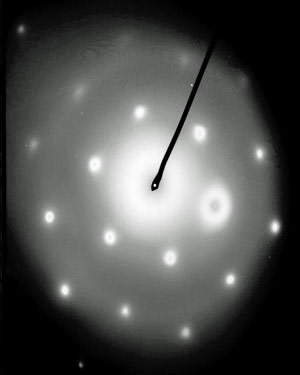

- Nanodiamonds: microscopic diamonds formed when a carbon source is subjected to an extreme impact, often found in meteorite craters.

- Lonsdaleite: a rare type of diamond, also called a hexagonal diamond, only found in non-terrestrial areas such as meteorite craters.

Three Choices at the Crossroads of Oblivion

Tankersley says while the cosmic strike had an immediate and deadly effect, the long-term side effects were far more devastating – similar to Krakatoa’s aftermath but many times worse – making it unique in modern human history.

An image of the X-ray diffraction pattern of lonsdaleite, or hexagonal diamond, from Sheriden Cave. Credit: University of Cincinnati

In the cataclysm’s wake, toxic gas poisoned the air and clouded the sky, causing temperatures to plummet. The roiling climate challenged the existence of plant and animal populations, and it produced what Tankersley has classified as “winners” and “losers” of the Younger Dryas. He says inhabitants of this time period had three choices: relocate to another environment where they could make a similar living; downsize or adjust their way of living to fit the current surroundings; or swiftly go extinct. “Winners” chose one of the first two options while “losers,” such as the wooly mammoth, took the last.

“Whatever this was, it did not cause the extinctions,” Tankersley says. “Rather, this likely caused climate change. And climate change forced this scenario: You can move, downsize or you can go extinct.”

Humans at the time were just as resourceful and intelligent as we are today. If you transported a teenager from 13,000 years ago into the 21st century and gave her jeans, a T-shirt, and a Facebook account, she’d blend right in on any college campus. Back in the Younger Dryas, with mammoth off the dinner table, humans were forced to adapt – which they did to great success.

Weather Report: Cloudy With a Chance of Extinction

That lesson in survivability is one that Tankersley applies to humankind today.

“Whether we want to admit it or not, we’re living right now in a period of very rapid and profound global climate change. We’re also living in a time of mass extinction,” Tankersley says. “So I would argue that a lot of the lessons for surviving climate change are actually in the past.”

He says it’s important to consider a sustainable livelihood. Humans of the Younger Dryas were hunter-gatherers. When catastrophe struck, these humans found new ways and new places to hunt game and gather wild plants. Evidence found in Sheriden Cave shows that most of the plants and animals living there also endured. Of the 70 species known to have lived there before the Younger Dryas, 68 were found there afterward. The two that didn’t make it were the giant beaver and the flat-headed peccary, a sharp-toothed pig the size of a black bear.

Tankersley also cautions that the possibility of another massive cosmic event should not be ignored. Like earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes, these types of natural disasters do happen, and as history has shown, they can have devastating effects.

“One additional catastrophic change that we often fail to think about – and it’s beyond our control – is something from outer space,” Tankersley says. “It’s a reminder of how fragile we are. Imagine an explosion that happened today that went across four continents. The human species would go on. But it would be different. It would be a game changer.”

Breaking Barriers and Working Together Toward Real Change

Tankersley is a member of UC’s Quaternary and Anthropocene Research Group (QARG), an interdisciplinary conglomeration of researchers dedicated to undergraduate, graduate and professional education, experience-based learning, and research in Quaternary science and study of the Anthropocene. He’s proud to be working with his students on projects that, when he was in their shoes, were considered science fiction.

Collaborative efforts such as QARG help break down long-held barriers between disciplines and further position UC as one of the nation’s top public research universities.

“What’s exciting about UC and why our university is producing so much, is we have scientists who are working together and it’s this area of overlap that is so interesting,” Tankersley says. “There’s a real synergy about innovative, transformative, transdisciplinary science and education here. These are the things that really make people take notice. It causes real change in our world.”

Reference: “Evidence for deposition of 10 million tonnes of impact spherules across four continents 12,800 y ago” by James H. Wittke, James C. Weaver, Ted E. Bunch, James P. Kennett, Douglas J. Kennett, Andrew M. T. Moore, Gordon C. Hillman, Kenneth B. Tankersley, Albert C. Goodyear, Christopher R. Moore, I. Randolph Daniel, Jr., Jack H. Ray, Neal H. Lopinot, David Ferraro, Isabel Israde-Alcántara, James L. Bischoff, Paul S. DeCarli, Robert E. Hermes, Johan B. Kloosterman, Zsolt Revay, George A. Howard, David R. Kimbel, Gunther Kletetschka, Ladislav Nabelek, Carl P. Lipo, Sachiko Sakai, Allen West and Richard B. Firestone, 20 May 2013, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1301760110

Additional contributors to Tankersley’s research paper were James H. Wittke and Ted E. Bunch, Northern Arizona University; James C. Weaver, Harvard University; Douglas J. Kennett, Pennsylvania State University; Andrew M.T. Moore, Rochester Institute of Technology; Gordon C. Hillman, University College London; Albert C. Goodyear, University of South Carolina, Columbia; Christopher R. Moore, University of South Carolina, New Ellenton; Randolph I. Daniel Jr., East Carolina University; Jack H. Ray and Neal Lopinot, Missouri State University; David Ferraro, Viejo California Associated; Isabel Israde-Alcántara, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicólas de Hidalgo; James L. Bischoff, U.S. Geological Survey; Paul S. DeCarli, SRI International; Robert E. Hermes, Los Alamos National Laboratory; Han Kloosterman, Exploration Geologist; Zsolt Revay, Technische Universität München; George A. Howard, Restoration Systems; David R. Kimbel, Kimstar Research; Gunther Kletetschka and Ladislav Nabelek, Czech Academy of Science of the Czech Republic; Carl Lipo and Sachiko Sakai, California State University; Allen West, GeoScience Consulting; James P. Kennett, University of California, Santa Barbara; and Richard B. Firestone, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Funding for this study was partially provided by the Court Family Foundation, UC’s Charles Phelps Taft Research Center, the University of Cincinnati Research Council, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

“Of the 70 species known to have lived there before the Younger Dryas, 68 were found there afterward. The two that didn’t make it were the giant beaver and the flat-headed peccary, a sharp-toothed pig the size of a black bear.”

What about the wooly mammoths mentioned in the first paragraph?

“Herds of wooly mammoths once shook the earth beneath their feet, sending humans scurrying across the landscape of prehistoric Ohio. But then something much larger shook the Earth itself, and at that point these mega mammals’ days were numbered.”

“Imagine living in a time when you look outside and there are elephants (mammoths) walking around in Cincinnati,” Tankersley says. “But by the time you’re at the end of your years, there are no more elephants (mammoths). It happens within your lifetime.”

This research might indicate that it wasn’t the cosmic collision that extinguished the mammoths and other species, Tankersley says, but the drastic change to their environment.