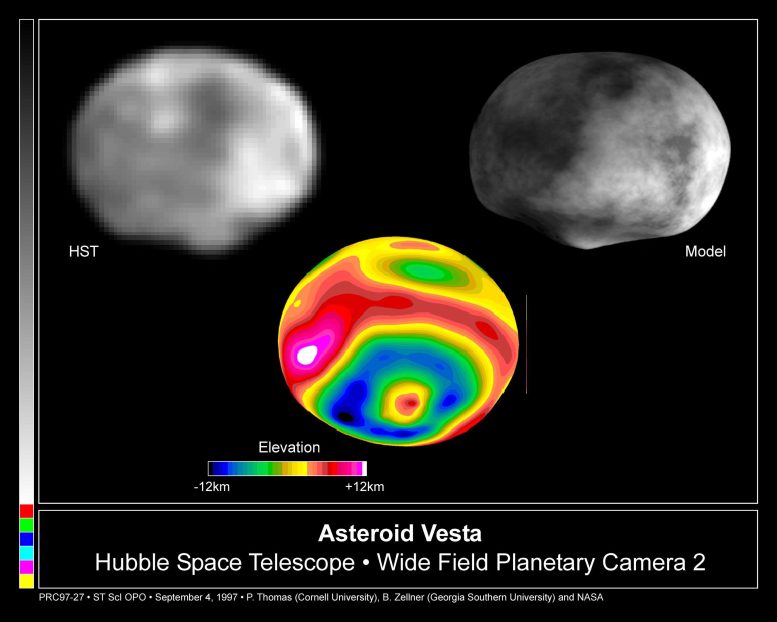

A NASA Hubble Space Telescope image of the asteroid Vesta, taken in May 1996 when the asteroid was 110 million miles from Earth. Diogenites meteorites, like those used in this study, may have come from the asteroid Vesta, or a similar body. Credit: Ben Zellner (Georgia Southern University), Peter Thomas (Cornell University), NASA/ESA

Scientists from the Carnegie Institution for Science are focusing on an old type of meteorite called diogenites to gain a better understanding of the earliest days of our Solar System and to help researchers understand the Earth’s birth and infancy.

In order to understand Earth’s earliest history—its formation from Solar System material into the present-day layering of metal core and mantle, and crust—scientists look to meteorites. New research from a team including Carnegie’s Doug Rumble and Liping Qin focuses on one particularly old type of meteorite called diogenites. These samples were examined using an array of techniques, including precise analysis of certain elements for important clues to some of the Solar System’s earliest chemical processing. Their work is published online on July 22 by Nature Geoscience.

At some point after terrestrial planets or large bodies accreted from surrounding Solar System material, they differentiate into a metallic core, a silicate mantle, and a crust. This involved a great deal of heating. The sources of this heat are the decay of short-lived radioisotopes, the energy conversion that occurs when dense metals are physically separated from lighter silicate, and the impact of large objects. Studies indicate that the Earth’s and Moon’s mantles may have formed more than 4.4 billion years ago, and Mars’s more than 4.5 billion years ago.

Theoretically, when a planet or large body differentiates enough to form a core, certain elements including osmium, iridium, ruthenium, platinum, palladium, and rhenium—known as highly siderophile elements—are segregated into the core. But studies show that mantles of the Earth, Moon and Mars contain more of these elements than they should. Scientists have several theories about why this is the case and the research team—which included lead author James Day of Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Richard Walker of the University of Maryland—set out to explore these theories by looking at diogenite meteorites.

Diogenites are a kind of meteorite that may have come from the asteroid Vesta, or a similar body. They represent some of the Solar System’s oldest existing examples of heat-related chemical processing. What’s more, Vesta or their other parent bodies were large enough to have undergone a similar degree of differentiation to Earth, thus forming a kind of scale model of a terrestrial planet.

The team examined seven diogenites from Antarctica and two that landed in the African desert. They were able to confirm that these samples came from no fewer than two parent bodies and that the crystallization of their minerals occurred about 4.6 billion years ago, only 2 million years after condensation of the oldest solids in the Solar System.

Examination of the samples determined that the highly siderophile elements present in the diogenite meteorites were present during formation of the rocks, which could only occur if late addition or ‘accretion’ of these elements after core formation had taken place. This timing of late accretion is earlier than previously thought, and much earlier than similar processes are thought to have occurred on Earth, Mars, or the Moon.

Remarkably, these results demonstrate that accretion, core formation, primary differentiation, and late accretion were all accomplished in just over 2 to 3 million years on some parent bodies. In the case of Earth, there followed crust formation, the development of an atmosphere, and plate tectonics, among other geologic processes, so the evidence for this early period is no longer preserved.

“This new understanding of diogenites gives us a better picture of the earliest days of our Solar System and will help us understand the Earth’s birth and infancy,” Rumble said. “Clearly we can now see that early events in planetary formation set the stage very quickly for protracted subsequent histories.”

Reference: “Late accretion as a natural consequence of planetary growth” by James M. D. Day, Richard J. Walker, Liping Qin and Douglas Rumble III, 22 July 2012, Nature Geoscience.

DOI: 10.1038/ngeo1527

Be the first to comment on "Diogenites Provide Clues of the Earliest Days of Our Solar System"