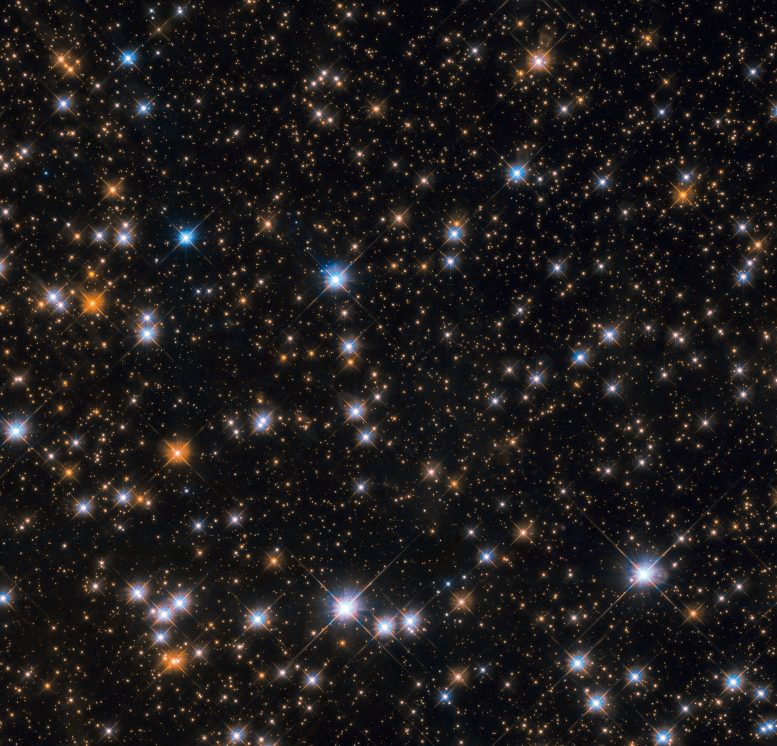

Hubble Space Telescope image of a portion of Messier 11, which is also known as the Wild Duck Cluster. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, P. Dobbie et al.

This star-studded image shows us a portion of Messier 11, an open star cluster in the southern constellation of Scutum (The Shield). Messier 11 is also known as the Wild Duck Cluster, as its brightest stars form a “V” shape that somewhat resembles a flock of ducks in flight.

Messier 11 is one of the richest and most compact open clusters currently known. By investigating the brightest, hottest main sequence stars in the cluster astronomers estimate that it formed roughly 220 million years ago. Open clusters tend to contain fewer and younger stars than their more compact globular cousins, and Messier 11 is no exception: at its center lie many blue stars, the hottest and youngest of the cluster’s few thousand stellar residents.

The lifespans of open clusters are also relatively short compared to those of globular ones; stars in open clusters are spread further apart and are thus not as strongly bound to each other by gravity, causing them to be more easily and quickly drawn away by stronger gravitational forces. As a result, Messier 11 is likely to disperse in a few million years as its members are ejected one by one, pulled away by other celestial objects in the vicinity.

I’m not sure where that Wild Duck Cluster is. Can you put a circle around it or mark it somehow? Thanks.

And *I’m* curious about the size of the area contained in this image. Is it one degree square, or 2°, or half a degree, or what? Thanks!

Okay, I answered my own question: the photo is 2.69 x 2.59 arcminutes in size, which is—let’s just use round numbers here—0.04, or 1/25th, of one degree, or 1/25th x 1/360th **2 (squared) of the entire sky from true horizon to true horizon, or, let’s put it another way, an almost infinitesimal amount of the sky. Somebody please correct me if I’ve dropped a decimal or something in my math here. Anyhow, my point is: count (if you can; I sure don’t want to try, myself) the number of stars you can see in this photo, and then square that number, and then multiply it by 25 x 360, and that might give you SOME idea of how many stars are “out there,” or at least how many Hubble can see. Amazing.