Conservationists should be wary of assuming that genetic diversity loss in wildlife is always caused by humans, as new research published today by international conservation charity ZSL (Zoological Society of London) reveals that, in the case of a population of southern African lions (Panthera leo), it’s likely caused by ecological rather than human factors.

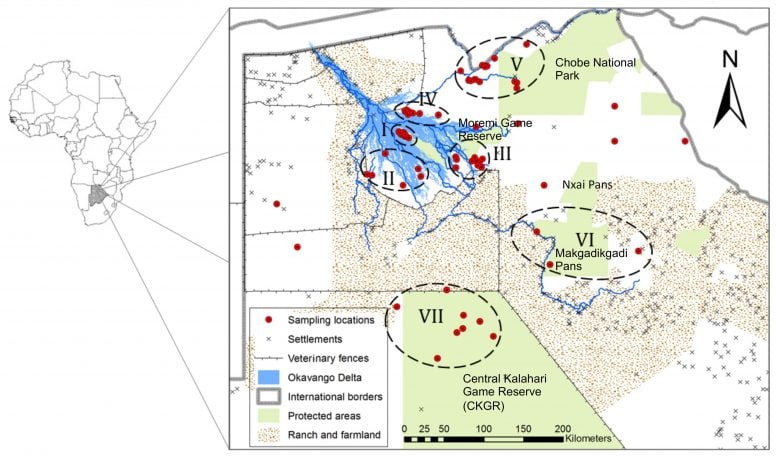

Published in Animal Conservation today (January 27, 2020) the study saw researchers from ZSL’s Institute of Zoology and Imperial College London analyze the genetic diversity of 149 African lions in the KAZA (Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area) in northern Botswana between 2010 to 2013.

While human impacts are the leading cause of genetic diversity loss in many cases, scientists studying the lions found that diversity loss across the population was instead caused by the lions’ need to adapt to differing habitats.

They identified two genetically different populations of lions in the region, each adapted to living in a distinct habitat type; the so-called ‘wetland lions’ residing in the wetland habitat in the Okavango Delta and a ‘dryland lions’ group living in the semi-arid habitat of the Kalahari Desert.

If a separate population is created but cut off from its original source group due to ecological or human barriers, over time there will be less gene flow from lack of breeding between the populations. While a larger more connected population would generally have greater genetic diversity, small amounts of movement between them can maintain diversity while preserving adaptations that allow them to thrive in two different environments. Though not different enough to be classified as separate sub-species and still having slight genetic movement between the populations, it suggests a phenomenon called phenotypic plasticity — animals adapting in various ways to suit the environment they’re in.

Ensuring wildlife conservation managers understand how a population becomes genetically fragmented is important in order that decisions regarding protection are well-informed and consider animals’ true needs.

Dr. Simon Dures, lead author and ZSL Researcher explained: “The findings have important applications for wildlife managers across Africa. It means translocations of animals, post-human-wildlife conflict, for example, need to be carefully considered with regard to their genetic predisposition to their new environment.

“The distinct ‘wetland lion’ populations living in the Okavango are incredibly well adapted to their environment. They’re strong swimmers and seem to thrive in the water chasing buffalo down for a kill — which is the opposite for other lions in Africa, which would not typically hunt in water. Moving these animals into a semi-arid environment could be detrimental to their survival.

“Animals need to be able to move freely in order to maintain a level of genetic diversity that builds resilience to changes in their environment caused by climate change, and we think this ecologically-induced separation of the lions pre-dates western Europeans’ colonization of southern Africa, so has likely been developing for a long time; way before people came with their fences and hunting.

Simon Dures stranded on the top of a Landrover after trying to cross a small river in Vumbura Plains region of Okavango. Credit: Michael Hensman

“Although we didn’t find humans to be the driving force here — it doesn’t mean to say they aren’t having any effect. Impacts such as persecution or increased development could lead to exacerbating inbreeding and threatening the future of these specially adapted lions.”

Reference: “Ecology rather than people restrict gene flow in Okavango-Kalahari lions” by S. G. Dures, C. Carbone. V. Savolainen, G. Maude and D. Gotelli, 27 January 2020, Animal Conservation.

DOI: 10.1111/acv.12562

African lions (Panthera leo)

African lions are currently classed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of threatened species with the number of adults between 23,000-39,000 and their population decreasing. Lions are now believed to survive in less than 17% of the area they occupied 150 years ago. Their threats in southern Africa range from livestock farming and ranching, habitat loss from housing and urban areas, hunting and trapping, war and civil unrest, and agricultural pollution. They are also largely targeted for the illegal wildlife trade with their body parts used for medicinal products and jewelry both at a local, national, and international level. Conservation actions include; education to mitigate human-wildlife conflict, ex-situ conservation breeding programs, and establishments of Protected Areas.

Human-wildlife conflict in Africa with lions

Human-wildlife conflict is an issue around the globe, and in Africa – lions often encounter urban settlements or cattle ranches. The lions will predate on the cattle as easy targets, or sometimes attack humans meaning local communities often retaliate by poisoning or hunting the lions. Wildlife managers will use translocation of the problem animal as a means of mitigating the conflict, moving the animal from an area of urban dwelling or cattle ranching to further afield areas. This research provides important applications for these mitigation plans, understanding the genetic predisposition of the individual to its environment before moving them. ZSL is also working across East Africa in areas affected by human-carnivore conflict, helping to develop community-led mitigation techniques and build financial resilience.

KAZA (Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area)

In December 2006 the governments of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe signed an MOU regarding the establishment of the KAZA TFCA. This covers an area stretching from Khaudum National Park in Namibia in the west to Lake Kariba in Zimbabwe in the east. Though not all areas are protected, the main objective is to join fragmented wildlife habitats into an interconnected mosaic of Protected Areas and transboundary wildlife corridors, which facilitate the movement of animals across international boundaries. The area provides migration routes for wildlife between Angola, Botswana, and Zambia.

Okavango Delta

The Okavango Delta based in northern Botswana is fed through water sources from Angola. However, 99% of this water evaporates during the dry season and has currently been dry for the last two years due to a long-term drought. Climate change has already impacted places like Victoria Falls just across the border in Zimbabwe, and the worry is that the Okavango could end up the same – with lions needing greater genetic diversity and reliance to adapt to changing environments, now more than ever.

ZSL (Zoological Society of London)

Founded in 1826, ZSL (Zoological Society of London) is an international scientific, conservation and educational charity whose mission is to promote and achieve the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats. Our mission is realized through our ground-breaking science, our active conservation projects in more than 50 countries and our two Zoos, ZSL London Zoo, and ZSL Whipsnade Zoo.

Be the first to comment on "Humans Not Always to Blame for Genetic Diversity Loss in Wildlife, New Conservation Research Reveals"