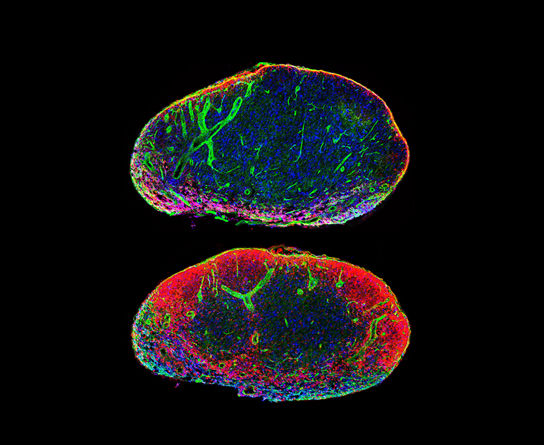

Two cross sections of a lymph node: macrophages, which appear as red in the top image, are sticky cells that act like flypaper, trapping viruses and bacteria when they enter the lymph node. Green and blue show other structural elements of the node. In the bottom picture, B cells are red and the structural elements of the node are in green and blue. Credit: Jake Miller, Harvard University

New findings are set to challenge the understanding of immune defense. In a recently published journal, researchers studied the response of mice to neurotropic vesicular stomatitis virus and found that survival after VSV exposure depends on B cells, but does not require antibodies or other aspects of traditional adaptive immunity.

New research challenges a well-established theory about antiviral immunity and may lead to a new understanding of the best way to help protect those exposed to potentially lethal viruses, such as rabies.

The findings contradict the current view that the production of antibodies, a part of what is called adaptive immunity, are absolutely required to fight off certain types of viral infection.

The study was published in the journal Immunity on March 23.

The immune system has two main branches, innate immunity, and adaptive immunity. Innate immunity, which we are born with, is a first line of defense that relies on cells and mechanisms that provide general immune responses. The more sophisticated adaptive immunity, which counts antibody-producing B cells as part of its arsenal, is thought to play a major role in controlling viral infections in mammals. However, adaptive immune responses, each tailored to fend off a particular pathogen, only develop after an initial infection. They also require time to become fully mobilized.

The researchers studied the response of mice to neurotropic vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), a member of the same family as rabies. VSV can cause flu-like symptoms in humans and is common in livestock and rodents. Mice infected with VSV can suffer fatal invasion of the central nervous system even as they generate a high concentration of anti-VSV antibodies in their system, explains senior study author Ulrich von Andrian, the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Professor of Immunopathology at HMS.

“This observation led us to revisit the contribution of adaptive immune responses to survival following VSV infection,” said co-author Matteo Iannacone, formerly a member of the von Andrian lab and now director of the Iannacone Lab, a Giovanni Armenise-Harvard Foundation Laboratory at the San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, Italy.

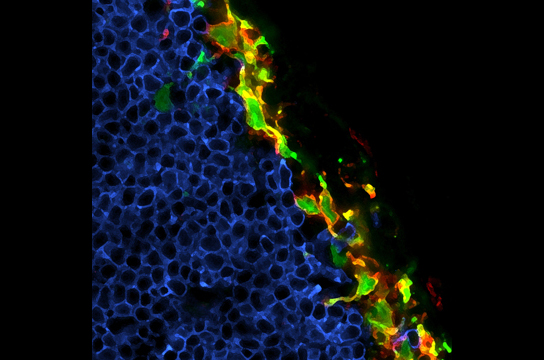

B cells (blue) migrate to follicles near the lymph node periphery, where they come into intimate contact with macrophages (red and orange). B cells produce proteins that allow the macrophages to replicate the virus. Viral replication (green) triggers type I interferon signaling, a potent alarm signal that initiates a cascade of antiviral defenses throughout the lymph and the surrounding tissues. Credit: Jake Miller, Harvard University

The research team studied VSV infection in B cell-deficient mice and in transgenic mice that had B cells but did not produce antibodies. Unexpectedly, while the former succumbed to VSV infection, the latter were completely protected. So survival after VSV exposure depends on B cells, but does not require antibodies or other aspects of traditional adaptive immunity.

Much of the work of the immune system takes place in the lymph nodes. There, innate immune cells called subcapsular sinus (SCS) macrophages act as a kind of flypaper, trapping viruses and other potential pathogens as they flow through the lymph. “We discovered an intimate relationship between the SCS macrophages and the B cells that is crucial for generating the rapid first response that prevents a dangerous systemic infection,” said first author Ashley Moseman, research fellow in microbiology and immunobiology in von Andrian’s group.

The researchers determined that the B cells produced a protein needed to maintain a unique protective function of SCS macrophages. This crucial signal from the B cells enabled the SCS macrophages to produce type I interferons, which were required to prevent fatal VSV invasion.

“It will be important to further dissect the role of antibodies and interferons in immunity against similar viruses that attack the nervous system, such as rabies, West Nile virus, and encephalitis,” von Andrian said.

Reference: “B Cell Maintenance of Subcapsular Sinus Macrophages Protects against a Fatal Viral Infection Independent of Adaptive Immunity” by E. Ashley Moseman, Matteo Iannacone, Lidia Bosurgi, Elena Tonti, Nicolas Chevrier, Alexei Tumanov, Yang-Xin Fu, Nir Hacohen and Ulrich H. von Andrian, 23 March 2012, Immunity.

DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.013

Be the first to comment on "New Findings Challenge Role of Antibodies"