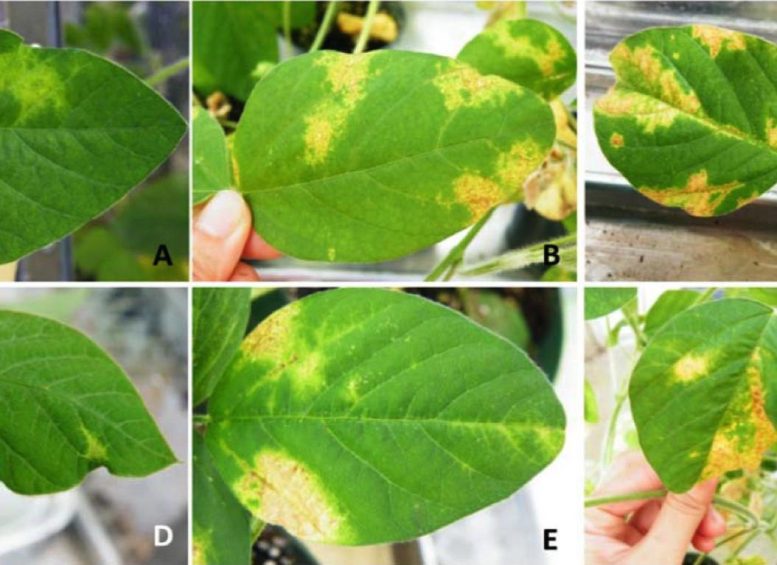

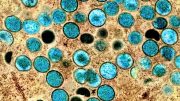

Soybean vein necrosis disease symptoms on soybean infected with soybean thrips fed on soybean vein necrosis-associated virus-infected material. A and D: Vein clearing in early stages of infection; B and E: turning to chlorosis; C and F: turning to necrosis and expanding to the majority of the leaf blade. Credit: Asifa Hameed

A soybean virus can actually benefit soybean thrips.

According to research from Penn State, most viral infections have a detrimental effect on an organism’s health, but one plant virus in particular, known as soybean vein necrosis orthotospovirus (SVNV), may actually be beneficial to a particular kind of insect that frequently feeds on soybean plants and can spread the virus to the plant, causing disease.

In a lab experiment, scientists from Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences discovered that soybean thrips, which are tiny insects that are between 0.03 to 0.20 inches long, had a tendency to live longer and reproduce more effectively than uninfected thrips.

Senior scientist of entomology at Ayub Agricultural Research Institute in Multan, Pakistan, Asifa Hameed, who conducted the research while earning her doctorate in entomology at Penn State University, said the results provide important insight into how the virus spreads in plants and impacts its insect hosts.

Asifa Hameed led the study while completing her doctoral degree in entomology at Penn State. Credit: Asifa Hameed

“In addition to prolonging the life of the insects, SVNV infection also shortened the doubling time of soybean thrip populations,” Hameed said. “This means infected thrips populations grew much more quickly, which could enhance the spread of the virus to additional soybean plants.”

The scientists noted that the disease soybean vein necrosis which damages soybean plants is brought on by SVNV. They recently reported their findings in the journal Insects. It may be transmitted by infected soybean thrips or infected seeds. Thrips contract the virus as larvae by eating on infected leaves and may subsequently spread the virus to other plants through their saliva, mostly during thrips’ adulthood.

When a plant becomes infected with the virus, the pathogen affects the veins of the leaves, turning them yellow. This yellowing may then extend to other areas of the leaves, eventually resulting in brown lesions. If the disease progresses long enough, the leaves become necrotic and fall off. SVNV may also reduce the amount of oil and proteins in seeds, as well as the rate of germination and seed weight.

Cristina Rosa, associate professor of plant virology in the College of Agricultural Sciences, said because the virus was discovered in 2008 and therefore is relatively new, not much is known about how to predict or manage the disease.

“Since there are no cures for plants infected with viruses, control of the virus vectors [thrips] is one of the best options for virus disease management,” she said. “Knowing the identity, biology, transmission propensity, and changes in behavior and physiology of the thrips that transmit soybean vein necrosis virus is fundamental to designing soybean vein disease prevention programs and to calculating the economic threshold of any intervention.”

To begin the study, the researchers collected soybean thrips from soybean fields at the Penn State Russell E. Larson Agricultural Research Center before releasing them onto soybean plants in the researchers’ lab. Thrips and plants were monitored regularly for SVNV infection using real-time polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, testing.

The researchers then monitored the thrips through two generations, noting variables such as lifespan, mortality, fertility, and reproduction.

After analyzing the data, the researchers found that the prepupal stage as well as the total immature lifespan and adult lifespan were all shorter in thrips not infected with the virus. Overall, the infected thrips tended to survive longer.

“We also found that infected thrips tended to produce more offspring,” Hameed said. “On average, uninfected females produced 84 eggs on average while those infected with SVNV produced 89.”

The researchers also calculated the population doubling time, which is the amount of time it takes a population to double in size. Among uninfected thrips, the doubling time was around four days. In the SVNV-infected population, the doubling time was just half a day.

While more research is needed to better understand the interaction between soybean thrips and SVNV, the researchers noted that one possible explanation for why SVNV resulted in increased survival for the thrips may be an increase of amino acids in the virus-infected plants, which may have benefitted the insects.

Reference: “The Effect of Species Soybean Vein Necrosis Orthotospovirus (SVNV) on Life Table Parameters of Its Vector, Soybean Thrips (Neohydatothrips variabilis Thysanoptera: Thripidae)” by Asifa Hameed, Cristina Rosa and Edwin G. Rajotte, 14 July 2022, Insects.

DOI: 10.3390/insects13070632

The study was funded by the Pennsylvania Soybean Board, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the Fulbright organization.

Be the first to comment on "Peculiar Plant Virus Causes Bugs To Live Longer"