Researchers have discovered that ravens and humans interacted significantly more than 30,000 years ago, suggesting that ravens fed on human hunters’ mammoth scraps and possibly served as a supplementary food source. The research implies that human activities had a significant impact on ecosystems and promoted synanthropy (the beneficial sharing of habitats with humans), affecting both human culture and the likelihood of zoonotic disease transmission.

Scientists from the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment examine human-raven relationships.

Long before the establishment of the first Neolithic settlements around 10,000 years ago, humans and wild animals had already formed diverse relationships.

An international study conducted by experts from the Universities of Tübingen, Helsinki, and Aarhus offers new insights into these interactions. They provide evidence showing that over 30,000 years ago, during the Pavlovian culture, ravens helped themselves to people’s scraps and picked over mammoth carcasses left behind by human hunters. This took place in the region known today as Moravia, in the Czech Republic.

The large number of raven bones found at the sites suggests that the birds, in turn, were a supplementary source of food, and may have become important in the culture and worldview of these people.

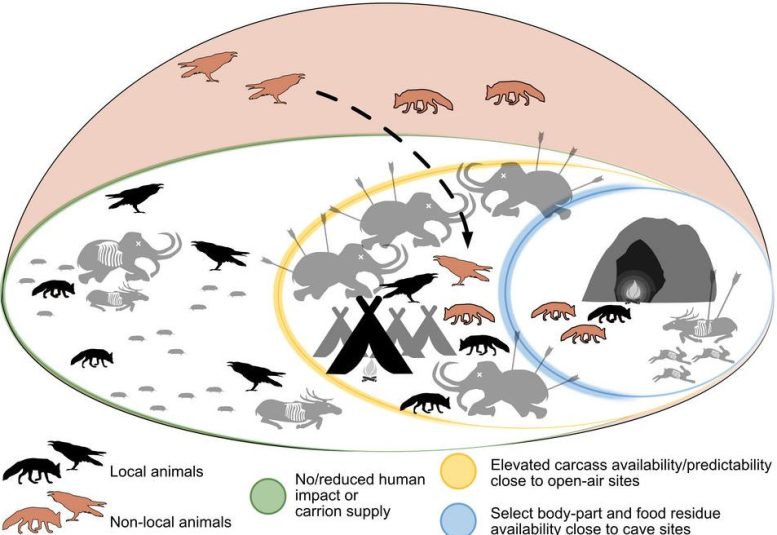

Relations between humans, ravens and other animals 30,000 years ago. Credit: University of Tübingen

The study’s lead authors are Dr. Chris Baumann, who currently conducts research at the Universities of Tübingen and Helsinki, and Dr. Shumon T. Hussain from Aarhus University, an expert in the deep history of human-animal interaction, along with Professor Hervé Bocherens of the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment.

The study has been published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

In an earlier study, published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, Chris Baumann described a general framework for the study showing that animal-human coexistence goes back deep into the Pleistocene. In it, he argued that such relationships likely shaped early ecosystems.

A similar food spectrum

Ravens have a very wide food spectrum, and are curious and flexible in their behavior. Their bones were discovered in large numbers at the archaeological sites of Předmostí, Pavlov I, and Dolní Věstonice I in southern Moravia.

“The number of raven remains at these sites is remarkable and very unusual for the time period,” says Shumon T. Hussain.

The researchers suspected that the ravens were living close to humans, perhaps attracted by their settlement activities.

The research team examined the bones of twelve common ravens from the sites and determined the birds’ diet by analyzing the nitrogen, carbon, and sulfur stable isotope compositions in the bones.

“These ravens fed predominantly on the meat of large herbivores, often mammoth, much like humans did at the time,” Chris Baumann explains. “We draw the conclusion that they were attracted to mammoth carcasses available near human camps.”

According to the team, the animals’ behavior was oriented toward what humans were doing in their environment. They say humans, in turn, took advantage of it, catching ravens, possibly for their feathers and meat. Such evidence is important for understanding early hunter-gatherer ecosystems.

The researchers propose that raven behavior was synanthropic, which means that the birds benefited from a shared ecosystem with human hunter-gatherers.

The myth of pristine nature

“It is often assumed that early human foragers lived in and with a practically untouched natural environment. However, this is certainly too simple. We now know that human behavior impacted and changed ecosystems at least 30,000 years ago and that this had important effects for other organisms,” says Chris Baumann.

Food scraps left by humans provided a stable food base for small scavengers and enabled novel human-adapted feeding niches to emerge. Such niches were exploited progressively over time and likely became key for some species, he says. At the same time, the respective animals became more important for human cultures.

A possible side-effect of these developments was the increased likelihood of zoonoses – infectious diseases which can be transmitted between humans and animals.

References: “Evidence for hunter-gatherer impacts on raven diet and ecology in the Gravettian of Southern Moravia” by Chris Baumann, Shumon T. Hussain, Martina Roblíčková, Felix Riede, Marcello A. Mannino and Hervé Bocherens, 22 June 2023, Nature Ecology & Evolution.

DOI: 10.1038/s41559-023-02107-8

“The paleo-synanthropic niche: a first attempt to define animal’s adaptation to a human-made micro-environment in the Late Pleistocene” by Chris Baumann, 20 April 2023, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

DOI: 10.1007/s12520-023-01764-x

Speculation, two people formed an opinion that humans were eating ravens based on number of bones found and evidence ravens ate meat. That doesn’t prove anything and is based upon the researcher’s theory and a baseless conclusion.

According to some people (not me) the earth is only around 6,000 years old which would make the 30,000 year old symbiotic relationship between humans and ravens impossible. The world is simply too young for such a relationship.

Considering that corvids are known to recognize and avoid humans that do them harm, how does this fit with the idea that they were hanging around human camps where they were being killed and eaten?

That thought occurred to me as well. I assume the authors have knowledge I do not that led them to that conclusion, but my first thought was to wonder how they ruled out that a population of corvids was simply coexisting with humans. Not as pets, but unmolested cohabitants. Markings on bones showing breakage/butchering of some kind would be my guess.

My parrot (a blue-fronted Amazon) wants to know how long the human relationship with parrots has been going on. 🙂

So,Hugin & Munin were real. Somehow that doesn’t surprise me.