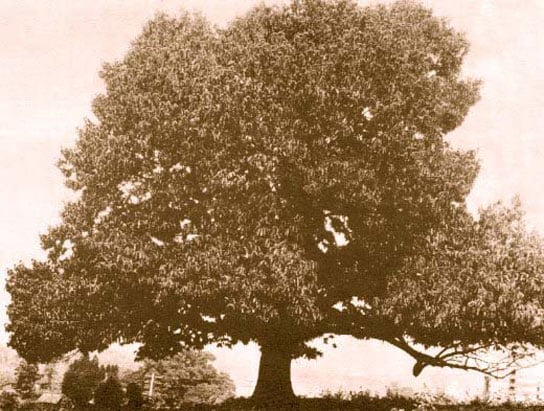

American chestnuts in the Great Smokey Mountains of North Carolina in 1910.

American chestnut trees are hard to breed but easy to kill. Scientists are trying to see if a hybrid of the Chinese and American chestnut trees will have enough resistance genes to keep the fungus called chestnut blight at bay.

The scientists published their findings in the journal Nature. Until a century ago, the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) was prosperous and plentiful in North American forests. The arrival of the chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) from Asia wiped out almost all of the trees. Since then, there has been an effort to try and revive the majestic trees.

Descendants of the original American chestnut tree were bred with a smaller Chinese variety (Castanea mollissima), which has a natural immunity to the Asian fungus. It has taken years of work, but it looks like some of the new hybrids are healthy.

Other researchers have been trying to create genetically modified trees to resist the fungus, and if successful, they would be the first GM forest trees released into the wild in the USA. This work could help save other trees like the elm and ash, which face a similar predicament as the American chestnut if nothing is done.

The American chestnut used to be known as the sequoia of the east, and was one of the tallest trees in North American forests. It dominated a range of 800,000 square kilometers (301,000 square miles) of forests from Mississippi to Maine, making up 25% of that forest. Its annual nut crop was a major food source for animals and humans alike. The decay-resistant wood was also used to make telephone poles, roofs, fence posts, and parts of the railway lines that crisscross the USA.

Back in 1904, rust-colored cankers were found to be developing on chestnuts. The blight came to America from Japan by hitching a ride on nursery imports of Japanese chestnuts that began in 1876. The fungal spores infected trees throughout America and within 50 years it had laid waste to almost the entire population of 4 billion trees.

Oak and other hardwoods filled the void, but didn’t produce a consistent crop of nuts year after year. Scientists started breeding hybrids of American and Asian chestnuts, which evolved alongside the blight. The attempts failed to produce any trees that were viable and resistant enough to the blight yet still retained American traits to make them a replacement. Asian chestnuts are shorter and less sturdy than their American counterparts.

In 1983, plant scientists formed the ACF in order to create a blight-resistant tree. The foundation grew to 6,000 volunteer members, including retired physicists and farmers. It maintains 486 regional breeding orchards and 120,000 experimental trees.

The “restoration chestnut” is 94% American and 6% Chinese and it seems to show a strong resistance to the blight. However, these Virginia trees might not thrive in other locations, so researchers are working on adapting them to other climates.

Researchers are also experimenting with chestnuts that contain genes thought to provide resistance, which were taken from Chinese chestnuts as well as plants such as wheat, peppers, and grapes. There are currently 600 transgenic trees available for different field trials to test their resistance to disease.

Researchers are working to develop a GM version of an American chestnut with strong resistance based on genes from Asian chestnuts. These cisgenic trees contain only genes of chestnut trees. There are efforts to use viruses to attack the chestnut fungus. Such viruses spread easily among the fungi and have been effective at controlling the blight in Europe; but since American fungal strains are more diverse, the virus cannot spread as effectively. Scientists have developed a transgenic fungus, which was designed to spread the virus more easily.

Most of the plant scientists agree that in order to restore the American chestnut, they will need a combination of fungal viruses and resistant trees, which could face further perils like the root rot mold (Phytophthora cinnamomi), the ambrosia beetles, and gall wasps.

Reference: “Plant science: The chestnut resurrection” by Helen Thompson, 3 October 2012, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/490022a

Be the first to comment on "Resurrecting the American Chestnut Tree"