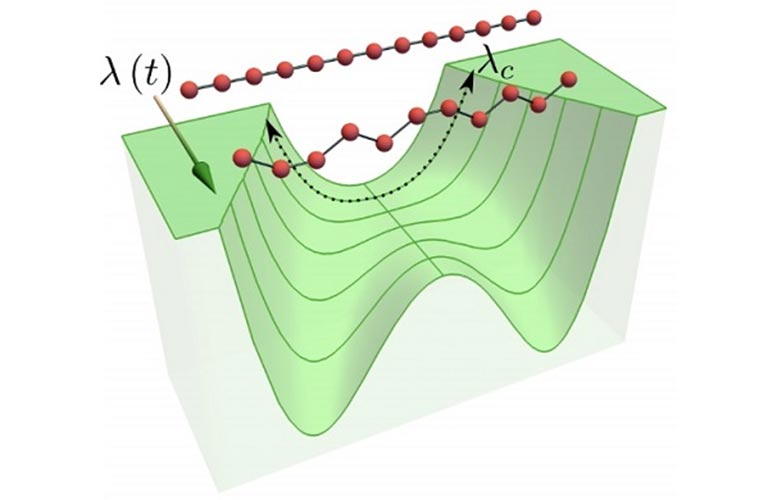

At the point at which the energy landscape splits, the high symmetry chain decays into a lower symmetry state when the critical point is passed. In this case, a straight chain decays into a zig-zag configuration when the anisotropy \lambda(t) passes a critical value \lambda_{c}. Where two consecutive ions fall onto the same side, a state of higher energy locally, we observe a defect. Credit: Fernando Gómez-Ruiz – Donostia International Physics Center

A summer internship in Bilbao, Spain, has led to a paper in the prestigious journal Physical Review Letters for Jack Mayo, a Master’s student in Nanoscience at the University of Groningen. He has helped to create a universal model that can predict the number distribution of topological defects in non-equilibrium systems. The results can be applied to quantum computing and to studies into the origin of structure in the early Universe.

Jack Mayo is a student of the Top Master Programme in Nanoscience at the Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials at the University of Groningen. Last year, he received an email, circulated by one of the program’s supervisors, with a list of summer internships that were offered by the Donostia International Physics Center (DIPC) in San Sebastián, Spain. One project caught his eye. ‘This was a theoretical project related to condensed matter, but it also had some clear technological relevance. I wanted to find out if this kind of work would suit me,’ he explains. Mayo applied and was selected, so he spent his 2019 summer holidays on the Basque coast, immersed in theoretical physics.

Ice crystals

The project that he participated in, together with the research group led by Professor Adolfo del Campo at the DIPC, was aimed at solving a problem in quantum computing – but it has much wider implications, from nanoscale magnets to the cosmos. In all these systems, the onset of order (for example, order induced by cooling) is almost always accompanied by the development of defects. ‘Take a system in which particles have a magnetic moment that can flip between up and down,’ Mayo explains. ‘If you increase their attractive interaction, they will start to align with each other.’

This alignment will begin at certain uncorrelated points in a medium and then grow – like ice crystals in water. The alignment of each domain (up or down in the example of the magnetic moments) is a matter of chance. ‘Local alignments will grow outwards and at a certain stage, domains will begin to meet and interact,’ says Mayo. For example, if an up-domain meets a down-domain, the result will be a domain wall at their interface – a symmetry-breaking defect in the ordered structure, leaving behind an artifact of the material in its higher-symmetry phase.

Traveling salesman

This annealing of a medium is described by the Kibble-Zurek mechanism, originally designed to explain how a phase transition resulted in ordered structures in the early Universe. It was subsequently discovered that it could be used to describe the transition of liquid helium from a fluid to a superfluid phase. ‘The mechanism is universal and is also used in quantum computing based on quantum annealing,’ explains Mayo. This technology is already on the market and is capable of solving complex puzzles such as the traveling salesman problem. However, a problem with this type of work is that defects that occur during the annealing process will distort the results.

Simulations

The number of defects that show up in quantum annealing depends on the time taken to pass the phase transition. ‘If you have millions of years to slowly change the interactions between units, you do not get defects, but that is not very practical,’ Mayo remarks. The trick is in designing finite-time – and therefore more practical – schedules to obtain an acceptable number of defects with high probability. The research project in which he participated was aimed at creating a model that could estimate the number of defects and guide the optimum design of these systems.

To do this, the physicists used theoretical tools to describe phase transitions and numerical simulations to estimate the defect distribution during cooling. As each domain can have one of two values (up or down in the example of the magnetic moments), they could estimate the chances of two opposite domains meeting and creating a defect. This led to a statistical model based on binomial distribution, which could be used to predict how a system should be cooled to create the smallest number of defects. The model was verified against independent numerical simulations and appeared to work well. This new model was described in a paper that was published on June 17, 2020, in Physical Review Letters and was accompanied by a ‘Viewpoint’ published in Physics, a comment on the results by the independent physicist Professor Smitha Vishveshwara from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Amsterdam

Now, almost a year later, Mayo is finishing his Master’s thesis in functional spectroscopy. He has learned that he has a taste for analytical work and, after graduating, he will start a PhD project in theoretical machine learning at the University of Amsterdam. ‘I am finishing up work on a quasi-classical approach to model the defects, which was also started in Spain. But first things first.’

Reference: “Full Counting Statistics of Topological Defects after Crossing a Phase Transition” by Fernando J. Gómez-Ruiz, Jack J. Mayo and Adolfo del Campo, 17 June 2020, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.240602

Be the first to comment on "Summer Intern Helps Develop New Model to Describe Defects and Errors in Quantum Computers"