The discovery of Bolg amondol, a name drawn from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, sheds new light on the complex evolutionary history of giant Gila Monster relatives.

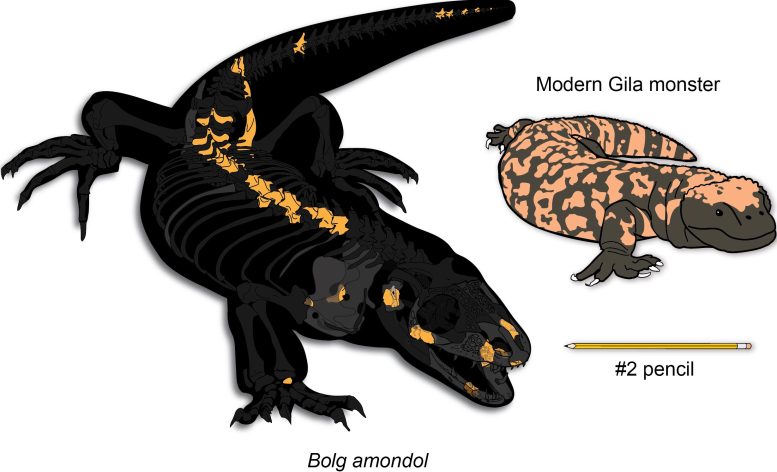

A raccoon-sized armored lizard newly identified from Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah highlights the unexpected variety of these giant reptiles during the height of the Age of Dinosaurs. The species, named Bolg amondol after the goblin prince in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, also provides insight into the complex connections that once linked ancient continents.

The study, published in the open-access journal Royal Society Open Science, was carried out by a research team led by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County’s Dinosaur Institute. Their findings emphasize not only the hidden scientific value within long-stored museum fossil collections, but also the remarkable potential of paleontological resources preserved in Grand Staircase-Escalante and other public lands.

“I opened this jar of bones labeled ‘lizard’ at the Natural History Museum of Utah, and was like, oh wow, there’s a fragmentary skeleton here,” says lead author Dr. Hank Woolley from the Dinosaur Institute. “We know very little about large-bodied lizards from the Kaiparowits Formation in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah, so I knew this was significant right away.”

A Moniker from Middle-earth

Bolg belongs to an evolutionary branch of large-bodied reptiles known as monstersaurs, whose living representatives include Gila monsters still found in the same desert landscapes where Bolg’s fossils were uncovered. When researcher Woolley recognized the need for a fitting name for the new species, he turned to one of the most celebrated creators of fantastical creatures: J.R.R. Tolkien. “Bolg is a great sounding name. It’s a goblin prince from The Hobbit, and I think of these lizards as goblin-like, especially looking at their skulls,” says Woolley.

To form the species epithet, Woolley drew on Tolkien’s Elvish language, Sindarin. In this language, “amon” translates to “mound” and “dol” to “head,” alluding to the mound-like osteoderms that characterize Bolg and other monstersaurs. The name “Mound-Headed Bolg” captures both its goblin-inspired imagery and its anatomical features, while also shedding light on the evolutionary story of these lizards.

Hidden Gems in Collection Drawers

“Bolg is a great example of the importance of natural history museum collections,” says co-author Dr. Randy Irmis from the University of Utah. “Although we knew the specimen was significant when it was discovered back in 2005, it took a specialist in lizard evolution like Hank to truly recognize its scientific importance, and take on the task of researching and scientifically describing this new species.”

The new species was identified from an associated skeleton of fragmentary bones: tiny pieces of the skull, vertebrae, girdles, limbs, and the bony armor called osteoderms.

“What’s really interesting about this holotype specimen of Bolg is that it’s fragmentary, yes, but we have a broad sample of the skeleton preserved,” Woolley says. “There’s no overlapping bones—there’s not two left hip bones or anything like that. So we can be confident that these remains likely belonged to a single individual.”

While most fossil lizards from the Age of Dinosaurs are known only from highly fragmentary remains—often nothing more than a single bone or tooth—the preserved pieces of Bolg’s skeleton, though incomplete, hold an extraordinary wealth of information.

“That means more characteristics are available for us to assess and compare to similar-looking lizards. Importantly, we can use those characteristics to understand this animal’s evolutionary relationships and test hypotheses about where it fits on the lizard tree of life,” says Woolley.

Additional fossils described in the research, including heavily armored skull elements, reveal that the ancient seasonal forests of what is now southern Utah, USA, supported at least three distinct lineages of large predatory lizards. “Even though these lizards were large, their skeletons are quite rare, with most of their fossil record based on single bones and teeth,” says co-author Dr. Joe Sertich from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Colorado State University. “The exceptional record of big lizards from Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument may prove to be a normal part of dinosaur-dominated ecosystems from North America, filling key roles as smaller predators hunting down eggs and small animals in the forests of Laramidia.”

Stairway to Monstersaurs

The Monstersauria are characterized by their large size and distinctive features like pitted, polygonal armor attached to their skulls and sharp, spire-like teeth. They have a roughly 100-million-year history, but their fossil record is largely incomplete, making the discovery of Bolg a big deal for understanding these charismatic lizards, and Bolg would have been a bit of a monster to our eyes.

“Three feet tip to tail, maybe even bigger than that, depending on the length of the tail and torso,” says Woolley. “So by modern lizard standards, a very large animal, similar in size to a Savannah monitor lizard; something that you wouldn’t want to mess around with.”

The identification of a new species of monstersaur highlights the likelihood that there were many more kinds of big lizards in the Late Cretaceous. Additionally, this find shows that unexplored diversity is waiting to be dug up in the field and in paleontology collections.

Bolg’s closest known relative hails from the other side of the planet in the Gobi Desert of Asia. While dinosaurs have long been known to have traveled between the once connected continents during the Late Cretaceous Period, the discovery of Bolg reveals that smaller animals also made the trek, suggesting there were common patterns of biogeography across terrestrial vertebrates during this time.

Dr. Woolley began this research as a PhD student at the Dinosaur Institute and has continued it as a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in the department, underscoring the value of funding scientific research and the unique role the Dinosaur Institute plays as a source of mentorship for young paleontologists.

“The Natural History Museum and Dinosaur Institute has been proud to lead the way in empowering early career scientists,” says Dr. Nathan Smith, co-author and Gretchen Augustyn Director & Curator of the Dinosaur Institute. In addition to Dr. Woolley, co-author Dr. Keegan Melstrom (now an Assistant Professor at the University of Central Oklahoma), was also a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Dinosaur Institute. “The result of that investment and continued growth of programs like the Dinosaur Institute Fellowship Fund is groundbreaking paleontological research and new discoveries that highlight the value of museum collections and expand our knowledge of Earth history.”

Field collection of the specimens described in this study was conducted under paleontological permits issued by the Bureau of Land Management.

The rocks where Bolg was discovered, the Kaiparowits Formation of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, have emerged as a paleontological hotspot over the past 25 years, producing one of the most astounding dinosaur-dominated records anywhere in North America with dozens of new species and critical insights into the past. Discoveries like this underscore the importance of protecting public lands in the western USA for science and research.

Reference: “New monstersaur specimens from the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah reveal unexpected richness of large-bodied lizards in Late Cretaceous North America” by C. Henrik Woolley, Joseph J. W. Sertich, Keegan M. Melstrom, Randall B. Irmis and Nathan D. Smith, 31 May 2025, Royal Society Open Science.

DOI: 10.1098/rsos.250435

This study was funded by the Bureau of Land Management, National Science Foundation award 2205564, the NHMLAC Dinosaur Institute, and the University of Utah.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.