A groundbreaking study has discovered the earliest known instance of leaf mining by insects in a 312-million-year-old fossil, pushing back the estimated origin of this behavior by 70 million years and providing new insights into the evolution and behaviors of early insects. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

Prehistoric insects, with their delicate and soft bodies, are challenging to preserve as fossils. While wings are more commonly fossilized, the bodies of these insects are often fragmented or incomplete, posing difficulties for scientific study. Paleontologists often rely on trace fossils to learn about these ancient insects, which are almost exclusively found as traces on fossil plants.

“We have a great fossil plant record,” said Richard J. Knecht, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard. “Further back in time, it’s the trace fossils that tell us more about the evolution and behavior of insects than the body fossils because plants and the trace fossils on them preserve very well. And the trace, as opposed to a body, won’t move over time and is always found where it was made.”

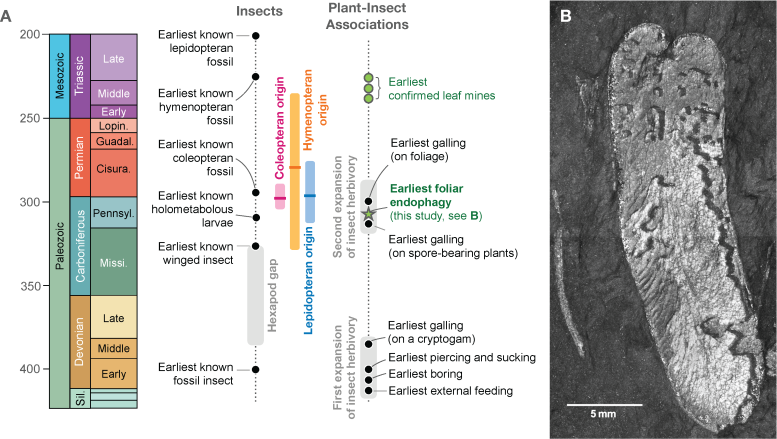

(A) Major fossil evidence for insects and plant-insect associations are presented with labeled points, with special reference to holometabolous insect orders (Diptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, and Coleoptera) and foliar endophytic damage. Genomic estimates of the origin of the major leaf mining orders are given in pink (Coleoptera), orange (Hymenoptera), and blue (Lepidoptera). (B) Fossil pinnule mines on Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri. (MCZ 198877a) from the Rhode Island Formation in Massachusetts, U.S.A. Credit: Anshuman Swain

Discovery of the Oldest Internal Feeding Evidence

In a new study, published in New Phytologist, researchers, led by Knecht, describe an endophytic trace fossil found on a Carboniferous seed-fern leaf that represents the earliest indication of internal feeding within a leaf. The 312-million-year-old Carboniferous fossil provides evidence of how internal feeding, known as leaf mining, may have originated and shows the age of this behavior was occurring approximately 70 million years earlier than believed.

“Of all of the ways that insects feed internally within plants—the mining of the insides of leaves, the tumor-like galls in which an insect takes control of the developmental machinery of a plant, the borings and galleries of insects in wood, and myriad ways that insects invade seeds to consume nutritious embryonic tissues—it is mining that has been the most mysterious,” said co-author, Conrad C. Labandeira, Senior Research Geologist and Curator of Fossil Arthropods at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. “The earliest mines are recorded from the Early Triassic, soon after the great end-Permian extinction, and yet galls, borings, and seed predation extend considerably earlier into the Paleozoic. Why the delay in mining? I think we now have an answer!”

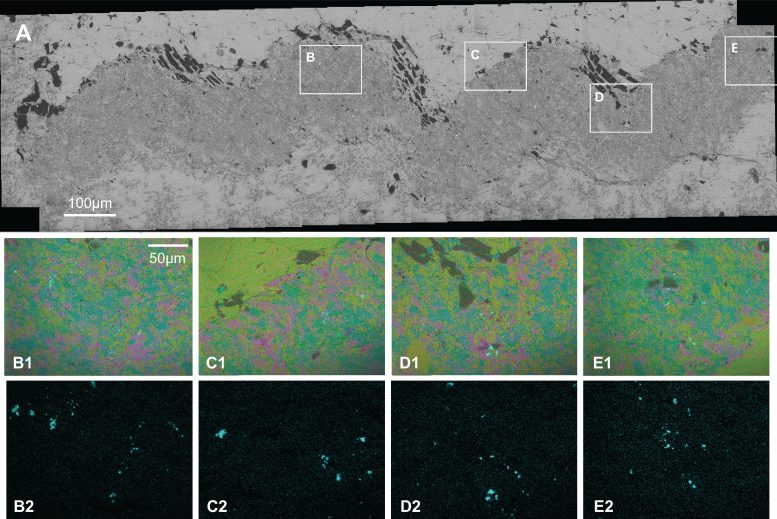

Backscatter and Energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) results of SEM analysis using a JEOL 7900F SEM. (A) SEM backscatter microscopy image of portion of endophytic trace. Boxes (B-E) represent areas where element mapping was conducted. B1-E1 shows stacked images of all elements found within the relative focused areas. Individual element maps of areas B-E can be found in supplementary data. B2-E2 represent element maps of phosphorus (cyan color) found in boxes B-E. Credit: Richard J. Knecht and Anshuman Swain

The Process and Importance of Internal Feeding

Internal feeding on plants is common among holometabolous insects – insects that undergo a full metamorphosis: Lepidoptera (moths), Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies), and Hymenopterans (wasps and sawflies). A larva bores into the leaf and begins to feed on the internal tissues of the leaf, leaving a trail behind. As the larva tunnels within the leaf, it is also growing, going through different stages of molting and even leaving behind its droppings, known as frass.

“Frass is one of the things we look for when we’re identifying internal feeding. Frass can even have different traits that are useful when it comes to defining what animal is making it,” Knecht said. The larva will continue to make a trail within the leaf until it pupates, hatches, cuts itself out of the leaf, and flies away.

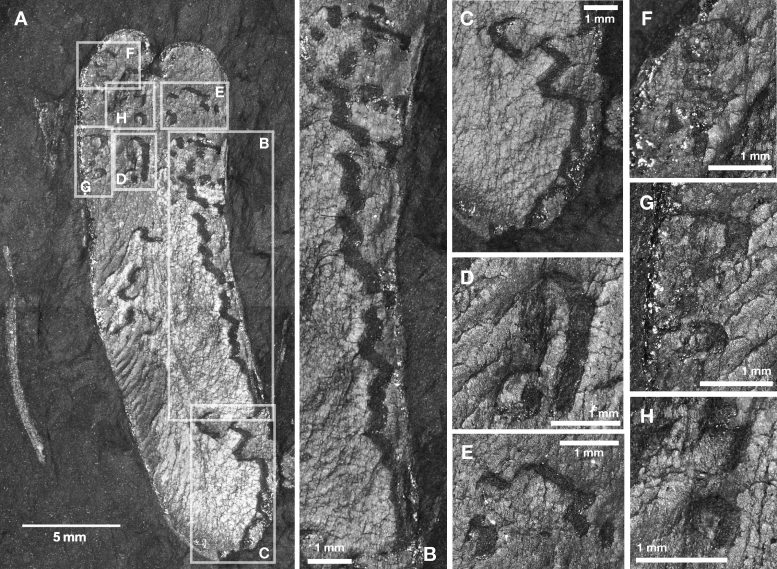

Endophytic traces on Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri; (A) MCZ 198877a (part) and magnified details of the endophytic structure (B)-(H). Credit: Richard J. Knecht

Exceptional Preservation in the Rhode Island Formation

The trace fossil was found in the Carboniferous Rhode Island Formation. The Rhode Island Formation was originally a swampy, water-logged environment which provided an anoxic setting that preserved plant fossils very well; what paleontologists call a Lagerstätte, a site that produces extraordinary fossils with exceptional preservation.

“One thing that doesn’t fossilize is larvae,” said Knecht. “They are too delicate and small. So seeing something like this is really insightful because it tells us about larval behavior at a specific time, the late Paleozoic, in which we know very little about larvae.”

The exceptional preservation allowed the researchers to clearly see the endophytic trace which follows patterns paleontologists look for when defining this behavior, For example a meandering trail, the larva will avoid the leaf’s edges and major veins. This behavior is only known to be performed by holometabolous insects, including animals existing today.

“This finding pushes this behavior back by 70 million years,” said Knecht. “It’s showing us two things, one the behavior of larvae, something we don’t see in the fossil record because larvae typically don’t preserve. And two, that the evolution of full metamorphosis, holometabolism, existed at this time.”

The fossil is housed in the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard among other fossils Knecht is also studying.

Reference: “Endophytic ancestors of modern leaf miners may have evolved in the Late Carboniferous” by Richard J. Knecht, Anshuman Swain, Jacob S. Benner, Steve L. Emma, Naomi E. Pierce and Conrad C. Labandeira, 5 October 2023, New Phytologist.

DOI: 10.1111/nph.19266

Be the first to comment on "Ancient Insect Mysteries Solved: 312-Million-Year-Old Fossil Sheds Light on Behavior and Evolution"