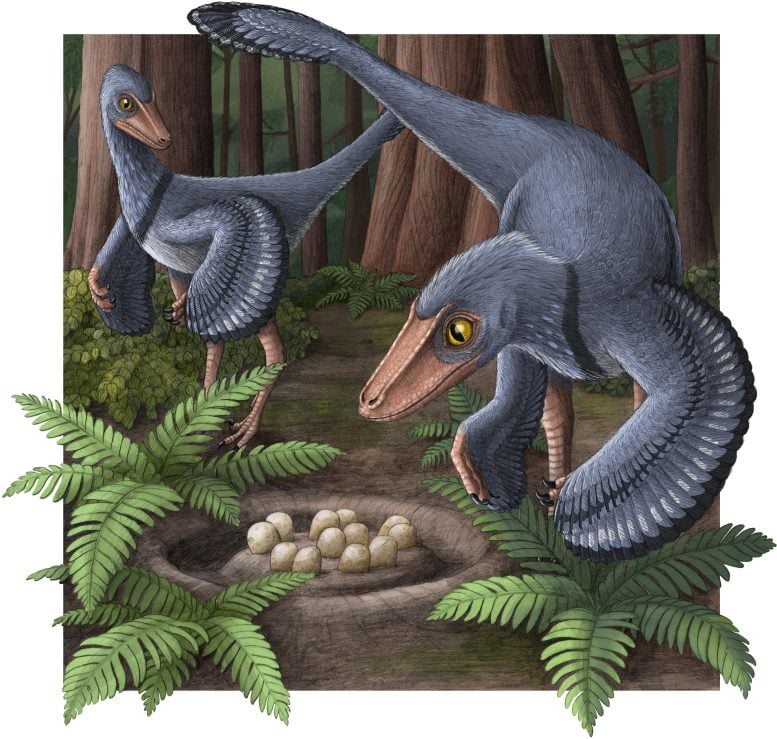

Several Troodon females laid their eggs in communal nests. Credit: Alex Boersma/PNAS

An international research team comprising scientists from Germany, Austria, Canada, the Netherlands, and the USA has utilized a novel carbonate analysis technique on eggshells from Troodon, reptiles, and birds.

Over millions of years and through a succession of gradual modifications, evolution has transformed a particular group of dinosaurs, the theropods, into the birds that we now observe soaring through the skies. In fact, birds are the only lineage of dinosaurs that managed to survive the devastating extinction event 66 million years ago that marked the end of the Cretaceous period.

The Troodon was one such a theropod. This carnivorous dinosaur measured approximately two meters in length and roamed the vast semi-arid regions of North America approximately 75 million years ago. Similar to some of its dinosaur counterparts, the Troodon possessed bird-like characteristics such as light and hollow bones. It walked on two legs and had fully evolved feathery wings, however, its relatively large size prevented it from taking flight.

Instead, it probably ran quite fast and caught its prey using its strong claws. Troodon females laid eggs more similar to the asymmetric eggs of modern birds than to round ones of reptiles, the oldest relatives of all dinosaurs. These eggs were colored and have been found half-buried in the ground, probably allowing Troodon to sit and brood them.

An international team of scientists led by Mattia Tagliavento and Jens Fiebig from Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany, has now examined the calcium carbonate of some well-preserved Troodon eggshells. The researchers used a method developed by Fiebig’s group in 2019 called “dual-clumped isotope thermometry”. By using this method, they could measure the extent to which heavier varieties (isotopes) of oxygen and carbon clump together in carbonate minerals. The prevalence of isotopic clumping, which is temperature-dependent, made it possible for scientists to determine the temperature at which the carbonates crystallized.

When analyzing Troodon eggshells, the research team was able to determine that the eggshells were produced at temperatures of 42 and 30 degrees Celsius. Mattia Tagliavento, leading author of the study, explains: “The isotopic composition of Troodon eggshells provides evidence that these extinct animals had a body temperature of 42°C, and that they were able to reduce it to about 30°C, like modern birds.”

The scientists then compared isotopic compositions of eggshells of reptiles (crocodile, alligator, and various species of turtle) and modern birds (chicken, sparrow, wren, emu, kiwi, cassowary, and ostrich) to understand if Troodon was closer to either birds or reptiles. They revealed two different isotopic patterns: reptile eggshells have isotopic compositions matching the temperature of the surrounding environment. This is in line with these animals being cold-blooded and forming their eggs slowly. Birds, however, leave a recognizable so-called non-thermal signature in the isotopic composition, which indicates that eggshell formation happens very fast. Tagliavento: “We think this very high production rate is connected to the fact that birds, unlike reptiles, have a single ovary. Since they can produce just one egg at a time, birds have to do it more rapidly.”

When comparing these results to Troodon eggshells, the researchers did not detect the isotopic composition which is typical for birds. Tagliavento is convinced: “This demonstrates that Troodon formed its eggs in a way more comparable to modern reptiles, and it implies that its reproductive system was still constituted of two ovaries.”

The researchers finally combined their results with existing information concerning body and eggshell weight, deducing that Troodon produced only 4 to 6 eggs per reproductive phase. “This observation is particularly interesting because Troodon nests are usually large, containing up to 24 eggs”, Tagliavento explains. “We think this is a strong suggestion that Troodon females laid their eggs in communal nests, a behavior that we observe today among modern ostriches.”

These are extremely exciting findings, Jens Fiebig comments: “Originally, we developed the dual clumped isotope method to accurately reconstruct Earth’s surface temperatures of past geological eras. This study demonstrates that our method is not limited to temperature reconstruction, it also presents the opportunity to study how carbonate biomineralization evolved throughout Earth’s history.”

Reference: “Evidence for heterothermic endothermy and reptile-like eggshell mineralization in Troodon, a non-avian maniraptoran theropod” by Mattia Tagliavento, Amelia J. Davies, Miguel Bernecker, Philip T. Staudigel, Robin R. Dawson, Martin Dietzel, Katja Götschl, Weifu Guo, Anne S. Schulp, François Therrien, Darla K. Zelenitsky, Axel Gerdes, Wolfgang Müller and Jens Fiebig, 3 April 2023, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2213987120

Be the first to comment on "Dino Discoveries: Troodon’s Surprising Nesting Habits Revealed"